There’s more to see at Town Hall aside from the plethora of events that we have taking place (you can check out our calendar here). There is art to see. Town Hall commissioned several artists to create permanent pieces that can be found throughout our building. In the south stairwell, for instance, you’ll see a poem written by local literary luminary Sarah Galvin.

Town Hall’s Jonathan Shipley recently sat down with Galvin to discuss her process, the poem, and gargoyle people.

JS: What’s your arts background?

SG: I started writing seriously in second grade. I was obsessed with Lord of the Rings and Narnia, and tried to write a novel about gargoyle people living on a planet made of ice cream. People told me I might be older when I finally got to publish, and I remember feeling so frustrated. I wanted to publish a book RIGHT NOW. I think as a service to little kid me I will actually try to publish that book, which was about 90 pages long, at some point. I started writing poetry when I was 14, after reading Ginsberg’s “Howl.” I was very into stream of consciousness writing at that age and what came out of that obsession was terrible. At 16 I began going to performances by this one-man-band called Sexually Active Corpse. SAC, a man named Will Waley, sang pornographic, surreal nursery rhymes over beats made with a Casio and an assortment of children’s instruments. My first real poems were sort of an imitation of his lyrics, which listed the hypersexual, surreal behaviors of a multi-gendered “speaker” with the ability to change bodies and travel through time, among other magic powers. The poems inspired by Will were also terrible. I finally began to write real poems when I realized that music, a beat, and a tune provided Will’s art a layer of meaning and a source of momentum that I needed to create somehow silently on the page. My first source of guidance for this was Joe Wenderoth’s “Letters to Wendy’s” which is (depending on who you ask) an epistolary novel or a series of poems using Wendy’s restaurant comment cards as a formal template. After gaining a rudimentary understanding of how to structure prose poems from “Letters to Wendy’s,” I started reading all the poetry I could find, and picked up techniques as I read.

JS: How did you become aware/get introduced to Town Hall?

SG: After I was accepted to University of Washington’s poetry MFA program, I went to see my soon-to-be thesis advisor, Heather McHugh, read at Town Hall. I had been freelancing at The Stranger, and when I walked into the auditorium, several people I knew from the paper smiled at me and beckoned to me to enter the room. It was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. I started to cry. I saw Heather, up on the stage, dressed as a bird in a flesh-colored spandex bodysuit, and all these people from the paper I could hardly believe had admitted me to work with them, and thought, “how do I deserve to be in this beautiful place with these geniuses? How can this be where I belong?” Ever since that night, I have had tender and reverent feelings about Town Hall. I believe it is a cathedral of art in Seattle.

JS: Why did you want to work with Town Hall with your poetry?

SG: It was an incredible honor, given my first experience of that space and what it has come to symbolize to me, to be asked to contribute a poem to be permanently on view there. I felt like I was completing something that began the first time I walked into Town Hall, answering for myself the question of whether I really could create anything worthy of the space. It is a magical place for me, in a way, the place where I went in a few steps from making a child’s art to making grown-up art. Town Hall for me has always physically manifested a right of passage. I was a student, now I hope it’s time for me to teach, to beckon the next generation of artists into that grand hall.

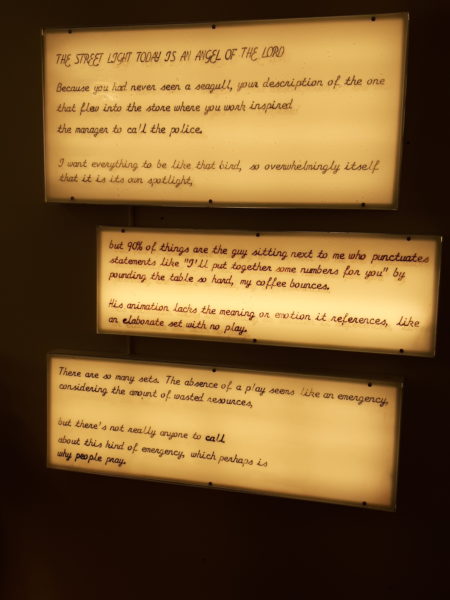

THE STREET LIGHT TODAY IS AN ANGEL OF THE LORD

Because you had never seen a seagull, your description of the one

that flew into the store where you worked inspired

the manager to call the police.

I want everything to be like that bird, so overwhelmingly itself

that it is its own spotlight,

but 90% of things are the guy sitting next to me who punctuates

statements like “I’ll pull together some numbers for you” by

pounding the table so hard, my coffee bounces.

His animation lacks the meaning of emotion it references, like

an elaborate set with no play.

There are so many sets. The absence of a play seems like an emergency,

considering the amount of wasted resources,

but there’s not really anyone to call

about that kind of emergency, which perhaps is

why people pray.

JS: What was the inspiration for the piece?

SG: Richard Kenney, one of my professors in grad school, was talking about poets in a lecture. He said something about how people look at poets like they’re crazy in their exaltation of mundane moments. Something like: “Without poetry, you walk up to somebody and say, ‘the streetlight today is an angel of the lord,” and they think you’re nuts. But you really saw that.” Exaltation of mundane moments is what poetry is all about. The primary project of art in any medium is to lift the veil of familiarity from life, which we need in order to function (imagine being blown away by every streetlight! You would never make it home from work.) When art works it makes every experience it exhibits feel like you’re experiencing it as a child again. Shortly after I met my wife five years ago, she said when she first got to Seattle as a teenager she worked at Urban Outfitters, and one day a seagull came into the store. Being from North Carolina, she had never seen one of our gigantic stretch Hummer seagulls before, so she called security and told them a “large waterfowl” had entered the building, and they better come quick. They of course laughed when they saw it was just a giant Dick’s fries-fed Seattle Seagull. It’s a love poem—I adored the exaltation of something familiar in her response to the trespassing seagull. Over and over, she makes my world new, gives me inspiration, and this poem expresses that facet of our love. Art is the core of our relationship in a lot of ways.

JS: What’s your process with your poetry? Is it systematic (specific times/places you write)? How much editing do you do after?

SG: I usually start with words from a conversation I found interesting. In this case it was Richard Kenney’s lecture. But it can be a sentence from a dream, something from social media, a poorly translated restaurant menu. I don’t think initially about what it “means,” I just follow a train of associations to create the poem. It feels like a desire to answer a question, like, what did that random sentence mean to me? Why do I keep thinking about this image? And because of the inspiration, my poems usually get their momentum from a poetic device called “anaphora” in which the same image or concept recurs and develops throughout a poem. I will write for four or five hours, finessing the same small set of words, then let the draft sit for a week or two, after which I dive back in for an intense round of editing that lasts vastly different lengths of times based on the length and complexity of the poem. Very occasionally, a poem just appears in 20 minutes in exactly the form it should be.

JS: Are there specific messages you’re wanting to convey in your work or are you opening it up to readers to give their own interpretations?

SG: I would say I hope the readers wind up in a similar emotional space after reading my poems, but I want that to be specific and personal to each of them. I want them to finish the poems with a sense of conclusion, yet with more questions than they had before they started reading. And I want them to feel deeply excited by the questions. You know how when people in cartoons turn invisible, sometimes somebody throws flour or a sheet over them and you can see someone’s there? That’s how poetry works for me. It outlines meanings that are too complex to be directly expressed with words. But I try to make the poems accessible—I want every reader to see that the invisible cartoon character is Donald Duck and not Mickey, even if they see an outline and not all of his features. It’s not language poetry, which tries to de-commodify poetry by completely relying on the reader to create meaning.

JS: What do you hope Town Hall attendees get from this particular piece?

SG: Well, as I mentioned the only words that can express what a poem is “about” are the exact words of the poem itself—I’m fond of the idea that “poetry is ‘about’ something the way a cat is ‘about’ the house—but this one is about love, and how when you really love someone, their day-to-day experiences fill you with wonder, awe and endearment. It’s also about how, as humans living through late-stage capitalism, we spend much of our time trapped in a sort of quantitative experience of life, and the little moments of love and art that free us from that. I hope people will read the poem and feel a renewed appreciation for the people they love and the moments of beauty those people bring. I hope they feel compelled to tell the important people in their lives they love them, and to make art.

JS: What’s next, artistically, for you?

SG: I just finished a new manuscript, which I sent to Black Ocean, the press that absorbed my previous press Gramma’s catalogue (which includes my most recent book, Ugly Time) when they closed down. I’ve been teaching a bit and want to teach way more! I love it. I just pitched a few classes to Hugo House, and ideally at some point I’d love to teach a class or two a quarter at Cornish, UW, or Central. I’ve been looking into how to make that happen. I also teach one-on-one writing lessons, so if you’re reading this and are interested, get in touch with me through my website! For those of you who have taken my classes, I’m sorry to say the price of the class no longer includes unlimited Jell-o shots, as I stopped drinking a year ago, but there will probably still be candy. Also, I like to write at least a couple of essays or reviews a month, and at the moment I have nowhere to publish them, so I’m looking for a publication to freelance regularly for. Oh, and I turned my blog, the Pedestretarian, a series of reviews of food found on the ground, into an Instagram, and I may either find a publication that will publish the reviews as a regular column, or start my own little printed publication. I’m also working on a book of essays.