This interview was conducted by Margaret O’Donnell, Artistic Director and Founder of the Seattle Playwrights Salon. Powered by Shunpike, the Seattle Playwrights Salon is a staged play-reading series founded in 2016. The Salon meets at Palace Theatre & Bar in Seattle from 7PM-9PM the second Friday of the month. It is one of the few regularly scheduled evenings in Seattle where playwrights and actors can bring new plays in development before an audience.

The interview below has been edited. You can read the full-length version here.

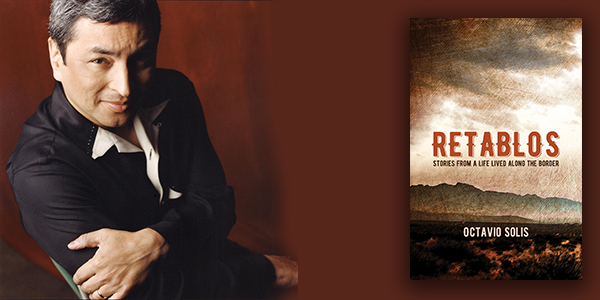

Octavio Solis will be on Town Hall’s stage on December 4 at the Rainier Arts Center discussing his new memoir Retablos: Stories From a Life Along the Border.

Octavio Solis will be on Town Hall’s stage on December 4 at the Rainier Arts Center discussing his new memoir Retablos: Stories From a Life Along the Border.

MO: You’ve been writing plays for nearly 30 years, and have had at least 25 of your plays produced. How have you changed as a playwright in these years?

OS: Oh, I have more unproduced plays in my folders. Theatres may commission works from a writer, but they’re under no obligation to produce them. Sometimes they don’t like the work. Sometimes the work is just not right for the time or their audiences. These works languish away in neglect, but sometimes they get cannibalized by other newer works.

I think my writing has changed quite a bit over time, but it’s because I’ve changed. We all must or else we become stagnant individuals stuck in some idealized time. Some things, however, still hold true. I still cling to the notions of theatricality—that is, the use of all the elements of live theatre to make the story vivid: lights, music and song, direct address, heightened language. I like works that dance across time and space, that bend these dimensions at will in the way Shakespeare did.

And yet at the same time, I think I’ve settled a bit. I like to focus more on people. I’m more inclined to slow the page down to let them talk. Too much effort is directed at moving the action forward, and not enough on moving the action inward. Each character is a kind of maze, and I am drawn to the language that acts as a kind of string that leads us into and out of the maze.

MO: Are the themes that interest you different than they were 30 years ago?

OS: Yes, I think I have absorbed some new themes into my oeuvre. For as long as I’ve been

a playwright of note, I have devoted myself to defining the American experience for Latinos in this country. The complexities, conflicts, and ironies of being an immigrant in America. The love for and struggle against the temptations of our consumer culture. The Mexican culture as it evolves into a new hybrid American society. What it means to live on the hyphen.

But now I am drawn to environmental issues. I think moving to the country, raising goats and chickens, living off our green garden; these new aspects of our rural life have awakened my environmental heart. Now as I see so much of our forests charred by wildfires, I am struck by how much of it is due to climate change. We’re at a tipping point. We have to respond to the dire

circumstances in our planet, even if we’re only the Cassandras and canaries in the coal mine.

MO: Has the way in which you get inspiration for your work changed over the years? How?

OS: Many companies have concerns they’d like me to address, so some commissions come with issues attached. Still, I have to find what matters to me. I have to be inspired to give them the play that they’re looking for. So often I ask, what is my way in? What about the issue or topic is personal to me? I have to care deeply or else I won’t care at all. What I look for is the element that will change me in the writing. I can’t be expected to change people’s perspective if I am not willing to be changed by the writing myself. So it’s always an education, always a discovery, which means there’s always a risk. By this, I mean that I have to be ready to have my beliefs upended by the work I do. I have to be ready to let the play talk to me directly and indirectly about things I have not considered about myself.

Latino playwright @OctavioSolis5 joins us at @RainierArts with his memoir Retablos—Stories from a Life Lived Along the Border Tuesday, December 4th. $5 tickets: https://t.co/2YwxJKlHH2 pic.twitter.com/Fx1sfICUbO

— Town Hall Seattle (@THSEA) November 12, 2018

MO: Have your writing habits changed over the years? What works best for you now?

OS: I used to write with fervor every day, every chance I could. I used to stand by my writing with a ferocity that permitted no challenges. I was young. There was still so much room to grow. Over the years, especially since writing is all I do, or at least the only occupation I have full-time, I used to demand that I write every day, all day, and when I was wasn’t I punished myself grievously by not going out and enjoying myself. Now, I know that was wrong. I have learned

that when I’m not writing, I am still writing. I am thinking and processing and engaging with my stories in my sleep, in my idle moments, when I’m driving my car; even when I am doing a repetitive physical task, I am writing. It’s the process before applying fingertips to keys or pen to paper. The dreamtime. The digestion of the idea. Consequently, I have parsed out my energies more wisely. I don’t write every day, but when I finally do sit down to write, I sit for six to eight hours and hammer out what needs to be written. Raw and unvarnished, ugly and badly worded. That’s what a first draft should be anyway. This process has become harder to maintain as I get older.

MO: What are you working on now?

OS: I’m working on getting the word out on Retablos, my new collection of memoir stories by doing readings and book-signings. I am working on a screenplay. I am doing the final touches on the rehearsal script of “Mother Road” which goes in rehearsal at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival this January for its premiere in March 2019. I am revising a work I had produced earlier this summer in Los Angeles. I am winterizing my farm in preparation for the first big freeze of the season.

Don’t miss Octavio’s event on December 4.