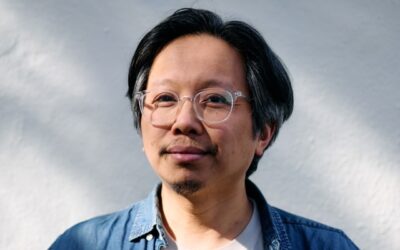

Tomo Nakayama, a multi-instrumentalist, singer, and songwriter from Seattle, recorded his first solo album Fog On The Lens during his 2014 artist residency at Town Hall Seattle. Now, as we celebrate...

Town Hall Seeks Artist In Residence to Create Land Acknowledgement Art

SUMMARY Stipend: $3,000 + up to $1,000 in production supplies. Additional benefits: access to Town Hall’s facilities, events, and speakers. Apply here. Town Hall is seeking an Artist in Residence...

What’s Your Curiosity Craving?

My life has been made better countless ways in countless times by the arts and those that make art.

What Are People Doing?

There was high praise in the August 2nd, 1919 edition of the Town Crier for the Theo Karle Club concert that was held at the Armory in honor of the Eastern Star delegates

Talent Show: The Tender Gritty Music of Amanda Winterhalter

On August 10, Town Hall’s stage will be graced by musician Amanda Winterhalter for a single release concert. Tickets are on sale now! Get to know her a bit more.

Town Hall Seattle Reads the Mueller Report

Mere days before Robert Mueller testified before the House Judiciary Committee regarding his special council report, Town Hall hosted more than 100 local actors, journalists, and community activists for a 24-hour marathon reading of the 448-page report in its entirety, including redactions and footnotes.

What Are People Doing?

“The Seattle Garden Club visited the gardens in The Highlands on Tuesday afternoon,” the Town Crier noted.

Duh: The Importance of Early Childhood Education

On July 17, in the Forum at Town Hall, there will be a screening of the documentary, No Small Matter, and a post-movie discussion about childcare access.

The film’s directors are Danny Alpert, Jon Siskel, and Greg Jacobs. Town Hall’s own Jonathan Shipley talked to Jacobs about early childhood education, brain works, and Cookie Monster.

What Orcas Can Teach Humans About Menopause and Matriarchs

Seattleites understand the draw of killer whales. Even a dorsal fin glimpsed from a ferry sparks awe. We want to be near their black-and-white bodies, their close family pods, their huge brains, their haunting songs.

But for writer Darcey Steinke, one quality above all others pulled her from her home in Brooklyn to the San Juan Islands in hopes of seeing a killer whale in the flesh: the fact that orcas and humans are two of only five species known to experience menopause.