For decades, the people of Colombia have been brutalized by a violent civil war fueled by drug money and billions of dollars in military aid from the United States. It’s the bloodiest and most intractable conflict in the Western Hemisphere but it remains poorly understood and seldom discussed in the U.S.

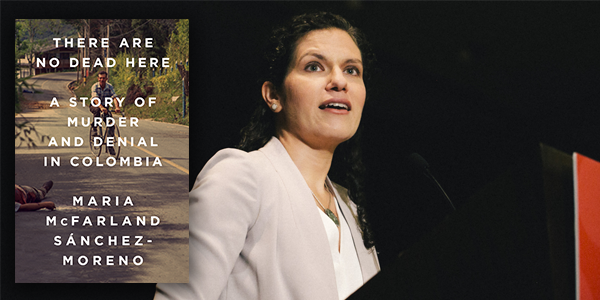

For insight into the plight of Colombia, Town Hall is proud to present Maria McFarland Sánchez Moreno, author of ‘There Are No Dead Here: A Story of Murder and Denial in Colombia’. Maria worked for over a decade at Human Rights Watch chronicling stories of violence and corruption in Columbia. Her new book reveals what she learned there, but also tells the story of courageous individuals who resisted paramilitary violence and provide some hope for justice and peace in that country.

She will be speaking about the book at a Town Hall event on Tuesday, March 27th but in the meantime I spoke with Maria about Colombia, the United States’ role there, and the intersectional consequences of the war on drugs throughout the world.

Get tickets for Maria’s upcoming event on 3/27.

EW: Thanks so much for talking to me. We’re very excited to be presenting you.

MMSM: I’m super excited about it! It will be wonderful to be in Seattle and to get to present the book there.

For many Americans the main thing they know about the Drug War and the conflict in Colombia is the story of Pablo Escobar. But your book actually begins after his death in the mid 90s, which far from ending the violence actually catapulted the country into a new phase of extreme conflict. So can you share a little bit about the context in which your story begins?

Yeah. So a lot of people think that Colombia is about Pablo Escobar and that after he died things somehow got better, but that’s not true. After Pablo Escobar was killed, other groups immediately stepped into his shoes and in particular people who were involved in getting him killed—a group called the Pepes, people persecuted by Escobar, who were former associates of his—immediately took the reins of the drug business. They were closely connected and in many cases they were the leaders of a paramilitary groups in Colombia, which claimed to be fighting left-wing guerrillas, claimed to be protecting people from abuses by the guerrillas, but in fact served as death squads for powerful interests and drug trafficking and became a huge factor in their violence. And so as they expanded throughout the 90s, they committed horrific massacres: killings of trade unionists, of community leaders, indigenous leaders, people who got in their way, and tried to spread terror in communities that were on territory that they wanted to control.

They would claim, for example, that a particular community was working with the guerrillas and use that as an excuse to go in and pull everybody out of their homes, commit a massacre, kill several people in front of their families, torture them, rape the women, in some cases a kill people in very gruesome ways, and in that way, force the rest of the community to flee in terror. So you had, even as the violence was happening, you had also this massive force displacement crisis where hundreds of thousands, eventually millions of people were fleeing the communities that they lived in—mainly rural communities— and moving into slums on the fringes of major cities.

The internal displacement crisis in Colombia prior to the Syrian civil war was one of the largest refugee crises in the world.

People don’t know that about Colombia. It’s also something that’s happened over many years and so people didn’t see it.

The conflict in Colombia can be so grim and the accounts of the violence can be so chilling that I was happy to see that you structured your book around profiles of activists who were able to mount effective resistance, some of whom paid with their lives. Can you tell us the story of one of these characters and why you approached the book this way?

When I was covering Colombia for Human Rights Watch, I got to know so many people in the country who had, despite all the pressures against them, all the pressures to either work with criminal organizations or armed groups or at least look the other way from their abuses, these people had insisted on standing up to those pressures and instead pressing for what they thought was right for justice, for truth, for basic human rights. And these are often very ordinary people who just could not go with the flow even though it would’ve been much easier and safer for them to do so. And those stories were never told in the United States. Most of the stories that come out of Colombia in the U.S. are either about Pablo Escobar or maybe you hear a little bit about the FARC’s kidnappings or you hear about DEA agents as the heroes.

When the real heroes I got to know were very different. So I started working on the book, focusing on this one character named Iván Velásquez, who I got to know when I was covering Colombia for Human Rights Watch. And he was an assistant justice on the Colombian Supreme Court, which has jurisdiction to investigate congress. He, one day was sitting in his office and received a complaint. It was very simple. It said: the paramilitary leaders who are negotiating now with the government on the terms of a supposed peace deal have claimed that they have friends in 35% of Congress. Please investigate this. This is very disturbing. And Iván Velásquez, who had had a history of investigating paramilitary crimes and other positions in the past, could have set that aside. He knew how dangerous it would have been to really go after the paramilitaries or their allies in Congress.

But he decided to take a look and there wasn’t much to go on. He started looking at old case files that were lying around in the court that might point in the right direction. And he started finding that there were a whole bunch of old case files that included evidence that was relevant and slowly he started finding witnesses and he built a series of cases against members of Congress eventually leading to what became known as the parapolitics scandal, where about a third of the Colombian congress ended up in prison for working with the paramilitaries, conspiring with them to commit electoral fraud, and in one case, murder.

Another party in this conflict is the United States. What was Plan Colombia, when did it start and what were its goals?

Well, the United States has been in involved with Colombia for decades. The war on drugs officially started in the 1980s and the US started increasing its aid to Colombia around then in the late 90s after a peace negotiation with the FARC guerrillas failed the US started Plan Colombia, which was a massive influx of mostly military aid into the country, meant to supposedly help with counter-narcotics but also provide greater security in the country, more order. And unfortunately because of that, because the vast majority of that money was going to the military, in practice the US was supporting a party in the conflict that was working with paramilitaries who themselves were among the country’s biggest drug traffickers. So in terms of fighting the war on drugs that didn’t really make any sense,

What has the Trump Administration’s policy been towards Colombia?

Well, it’s interesting, the Trump administration has been very critical of the Colombian government. The government a few years ago suspended areal fumigation of cocoa crops. In part that was because the WHO itself has said that glyphosate, which was being used to fumigate the cocoa crops, could produce cancer. And so they made this decision, they stopped it, the US didn’t like that. And then it appears that the Trump administration doesn’t like the peace deal with the FARC and cocoa production has gone up in recent years due to a variety of factors. And so Trump is approaching this long-time ally by threatening them and saying that he might remove them from the list of countries that cooperates with us on narcotics. So it’s a very aggressive, hostile approach at a time when Colombia is maybe starting to shift policy.

This isn’t that surprising because Trump, when it comes to the war on drugs, has been completely over the top. I mean, he and Jeff Sessions not only wanting to go back to the most aggressive harshest way of talking about the war on drugs, but they want to go even further and so you have Trump recently calling for the death penalty for people who sell drugs.

I’ve never heard of a dealer who kills 1,000s and gets 10 days @realDonaldTrump . You already have absurdly “tough” sentences. #factcheck

— Maria McFarland SM (@MMcFarlandSM) March 19, 2018

Echoing Duterte, the president of the Philippines.

Praising Duterte! And so it’s not surprising he’s using the war on drugs domestically as a way to get his base riled up. You know, the war on drugs within the United States has always targeted primarily people of color and he is using it clearly as an excuse to go after immigrants in particular. And against people who he’s stigmatizing as undesirable—people who sell drugs, people who use drugs. It’s easy to demonize and then get people angry and then say “let’s kill them,” even if that does absolutely nothing to solve any problems.

For more about the human rights crisis in the Philippines, check out Town Hall’s April 6th event PANALIPDAN! DEFEND!

And that’s a nice segue into the last thing I wanted to ask you about, because a lot of the research into this book was done in your previous role at Human Rights Watch, doing watchdog work in Colombia, but you recently moved to a new position as the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance. A lot of people in the Pacific Northwest are very proud of our region’s forward-thinking policies on drugs and marijuana decriminalization and later legalization.

And LEAD and supervised consumption sites!

What do you see as the relationship between organizing to resist the Drug War domestically and your previous work and the subject of this book which touches on the impacts of the Drug War internationally?

For me, the War on Drugs is a root cause of many of the social justice problems that I’ve tried to tackle throughout my career. So in Colombia I saw how the War on Drugs meant that this created this huge illicit market in drugs that fueled organized crime, that gave them this enormous power and ability to corrupt authorities and undermine democracy and kill people in enormous numbers. Later on I worked more internationally and I saw very similar patterns in Afghanistan and Mexico again: the drug trade fueled by prohibition in turn leading to massive violence and corruption. But then later on I worked on the US as co-director of the US program at Human Rights Watch and I worked on criminal justice issues here and immigration and national security issues. And again, I saw how the War on Drugs was this major factor fueling the mass criminalization of people in the United States.

In other words millions of people getting arrested in most cases for nothing more than consuming drugs. So possessing drugs for personal use. Overwhelmingly these arrests are affecting people of color. Even though black and brown people use drugs at the same rate as whites, they are arrested for using those drugs three times as often as white people. So many people are deported because of low-level drug offenses. For simple marijuana possession, many, many immigrants end up deported. Even green card holders who would otherwise be allowed to stay. The War on Drugs has even been used as an excuse to justify mass surveillance both in the US and abroad. So to me this is a critical issue that we need to address that we can also tackle so many other social justice problems that I care about.

Well, thank you so much for doing this work and for writing this book.

Thank you so much. I’ll say one, one more little thing. I think the book in addition to getting people to think about the war on drugs, I hope it inspires people because we’re talking about characters in this book who are ordinary people yet made tremendous change possible in their country, even under the most dire of circumstances. And if that was possible for them in Colombia, it’s certainly possible for people who are fighting for change in this country.

Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno will be speaking at Phinney Neighborhood Center on Tuesday, March 27 presented by Town Hall Seattle.