Town Hall and Fuse Washington collaborated for a Media is Dying panel discussion on July 11. Anya Shukla, a rising 11th grader at Lakeside School and a TeenTix Press Corps editor, was in attendance:

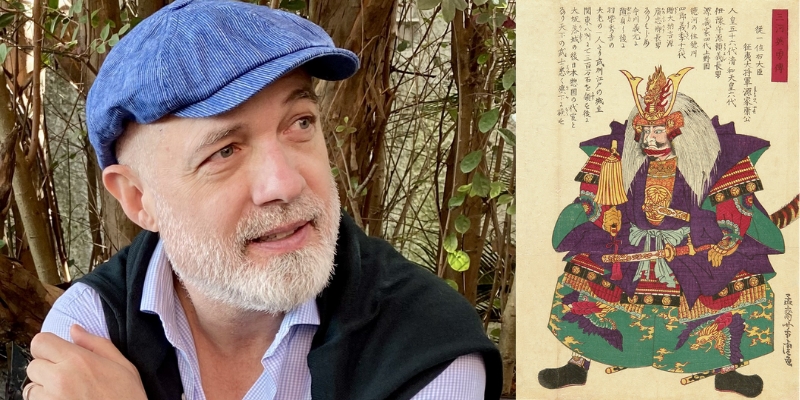

I didn’t know that the media was deteriorating. According to Bloomberg, journalism is decaying all around the country, at organizations such as Buzzfeed, Vice Media, and CNN. Even in Seattle, what many would consider an artsy, media-oriented city, the number of journalistic opportunities have dropped by 40%. These are the kinds of cold, hard, scary facts that I learned last week at Town Hall’s The Media is Dying panel, featuring Adrienne Russell, Clifford Cawthon, and Peter Jackson.

I could tell that I was out of my depth as soon as I walked into the event space, which was filled with local political chatter and orange YES t-shirts. I’m not exactly cut off from politics–I keep up with the New York Times–but compared to my fellow audience members, I knew nothing. I don’t pay attention to the goings-on in Seattle; I don’t know who our senators or representatives are. Further proof of my ignorance: I thought journalism was a viable career.

According to Jackson, the media’s slow and violent death is not because of a lack of interest–schools are overflowing with story-hunting, news-sniffing students. It’s not due to a lack of opportunity: the internet, with its ability to democratize the news system, has made it far easier for grassroots media organizations to thrive. So what’s the problem?

Unfortunately, the web is a double edged sword: although the internet opens doorways for smaller journalistic organizations, it is also responsible for many of the media’s current struggles. As a former newspaper editor in the audience told us, 65% of a newspaper’s revenue comes from advertisements, but only 15% of the paper’s income goes to the reporters. A decline in advertisers–perhaps because companies can now promote their content by paying Google or using strong search engine optimization–means a reduction in staff pay. As well, the internet makes it far easier for readers to stop subscribing to news: if you can find information anywhere, for free, why should you have to pay the Washington Post or the New York Times? Of course, less subscribers means less money for journalists. The world wide web, a once-brilliant beacon of hope and prosperity for newspapers, is now media’s downfall.

Money can also affect papers in ways one wouldn’t expect. Jackson let us in on a sobering truth: the best health information comes from a website associated with Kaiser Permanente. Some of the greatest photojournalists in Seattle work for the Starbucks Newsroom. Journalists have to go where the money is, and often, that money is in the hands of corporations focused on promoting their brand. Especially when your article might hurt the billion-dollar company that owns your paper, it can be hard to tackle hard-hitting stories. Reporters can’t bite the hand that feeds them, even though that goes against the necessity of telling the truth in journalism, of not sitting on important information, of being objective.

So the media is dying. But what can we do to slow its demise? Russell thought that, like in several Nordic countries, government should be required to pay for journalism. Newspapers are a public utility, after all. Jackson believed that we should foster a love for the news at an early age by having children share articles in school. This will pay off down the road, when those kids grow into adults with the power to subscribe–i.e. give their money–to whichever newspaper they choose. I think we need to get young people involved with their cities. Part of the reason I felt out of place at the panel was because I don’t keep up with local politics; I don’t know what I’m saying YES to. I don’t subscribe to the Seattle Times because I don’t think the goings-on of my town are as important as what’s happening in New York or Washington D.C.. If I felt that there was something Seattle could give me, something I could fight for or against, something I would want to read about in the paper, I’d be paying $3.99 a week for the rest of my life. Somehow, I need to become invested in Seattle at a local level, so that I can support our local newspapers. But hey–I’m young. I can change my mindset. I can still learn more about citywide politics, either in the classroom or through my own research. And I’m a quick learner: I now know that journalism is practically over; the presses have stopped. But, hopefully, one day, thanks to a shift in how we think about our towns and an increase in funding and subscribers, I’ll find out that they’ve started rolling again.