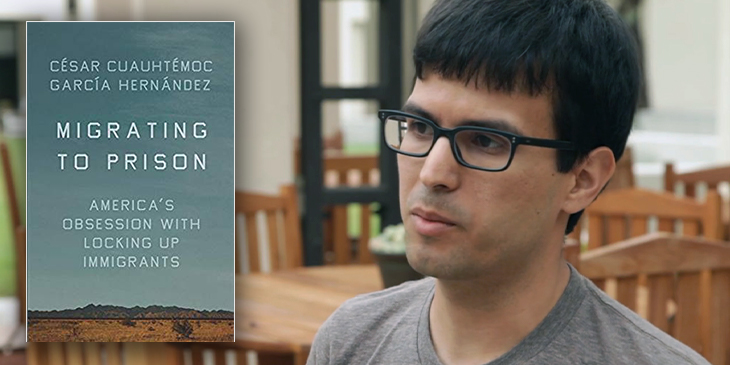

In this week’s interview, Chief Correspondent Steve Scher talks with César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández about the problems with our nation’s immigration prison system. Hernández outlines the financial incentives for private prisons to keep their cells filled in order to receive money from the government, and identifies similarities between immigration prisons and the mass incarceration of the 1980’s Reagan-era war on drugs. Hernández and Scher discuss the stigmas migrants face, as well as the factors perpetuating this prison system and what it would take to dismantle the immigration prison system. Get an insider’s look and stay in the know about what’s going on in this moment at Town Hall.

Episode Transcript

This transcription was performed automatically by a computer. Please excuse typos and inaccurate information. If you’re interested in helping us transcribe events and podcasts, email communications@townhallseattle.org.

Welcome to in the moment a town hall Seattle podcast where we talk with folks coming to our town hall stages and give you a glimpse into their topic, personality and interests. I’m your host, Ginny Palmer. It’s the beginning of December and as 2019 winds down so to our town hall programs, but don’t let the light listings on the calendar fool you. We’ve got some hard hitting events about racial and social justice and assortment of art and music programs to satiate your holiday spirit and with that same holiday spirit in mind, many of us look to help those around us in need. There are the obvious choices, food banks and homeless shelters, but there are also the places hidden from sight or behind fences and bricks like the immigrant detention centers that housed thousands of immigrants from across the globe. The U S imprisoned Chinese immigrants on angel Island in San Francisco Bay in the 1850s immigrants were detained to Ellis Island before they were allowed into the U S but for many decades of the nation’s existence, the Southern border with Mexico was more fluid.

People living on both sides could cross to be with family members or seek work, but that is all changed today. The U S puts around 400,000 people annually into detention to await some form of civil or criminal determination or their feet. Often their crime is the very fact that they crossed the border without the proper documents and who benefits from this harsh treatment of people fleeing their home countries in search of asylum or a better life lawyer says our quality Moke Garcia Hernandez was born on the U S side of the Texas Mexico border. He is a law professor at the university of Denver and is coming to town hall on December 9th to talk about his new book migrating to prison. America’s obsession with locking up immigrants are in the moment. Chief correspondent, Steve Cher spoke with CSR over the phone.

I just met with some folks yesterday, told him I was reading your book and they said, Oh, I have to read this book because we’re going down to the Northwest immigration detention center in Tacoma on a regular basis to try to help some of the people there. And talk to some people there and that’s their, that’s their reality right now. Yeah.

Those folks who are advocating at the Northwest detention center are really at the forefront of activism focused on, on the shutting down this, this practice that’s grown up over the last four decades or so. So those are good people to to, to learn from.

How much access do people actually get to the folks who are in these prisons?

It’s very hard to get inside these immigration prisons. The, the sad reality is that even lawyers tend to not to, to go into these facilities. Many of them are located far from large urban centers where you have substantial immigrant rights communities, social service communities, clergy, the kinds of folks who take take tend to take an an interest in the struggles of people who are, who are going through one, one prison system or, or another. And so what that, what that means on the ground is that when you go walk into, into immigration court hearings involving detained individuals, you’ll see that most of them are showing up there by themselves. That’s true of the adults. That’s true. The families. And that’s true of, of kids who as well,

What’s the justification for that? When you ask a immigrate you know, a, a person on the other side who’s representing the government Cost? It would, it would obviously come at a finance a substantial financial cost to the government to, to provide publicly funded immigration attorneys for, for everyone who’s going through the process.

But again, it’s costs or cost. How much do these systems cost the American taxpayer when people are, what is it, 400,000 annually to these prisons?

I think the number fluctuates between four and 500,000. But we’re talking regardless, we’re talking about a large number of, of individuals, most of whom are going to be going through the process without the assistance of, of, of lawyers. And, and, and not only is that, is it expensive to run these facilities, but it’s also expensive on the court system itself. The, the, the reality is that judges don’t really, immigration judges don’t really like seeing immigrants show up in their courtrooms standing alone either because they don’t know what’s going on. They, they you know, the, the judges then have the responsibility of trying to help out this person just so that they can raise some claim that maybe is good and maybe it’s not good, you know? And, and and, and lawyers actually are efficient.

They, they help identify when, when somebody’s got a good legal claim, when they don’t have a good legal claim. And, you know, sometimes the thing that a lawyer does is have that hard conversation with a client that says, look, you know, the reality is the way immigration law is currently structured, you’re out of luck. And that gives that, that gives an immigrant the information that they need to make a decision about how to, how to move forward. And, and, and, and from the perspective of the court system itself, you know, that, that’s actually quite helpful.

Well, that makes sense.

But somebody must benefit. Who do you think benefits from this privatized system of imprisoning? There’s, there’s, there’s lots of value that comes from locking up immigrants to begin with. The private prison corporations that run facilities around the United States core civic and the geo group are the two largest private prison operators in the United States, both of which have a heavy footprint in the immigration prison prison practice. But local officials are equally invested. Many times County governments either own or operate the immigration prisons that contract with ice. In other instances, the County will own the facility and contract with a private prison corporation that then goes out and gets the contract with the federal government. But regardless of how it’s structured County County governments quite frequently have a, have a financial interest at stake in keeping their prison beds filled. And then when the federal government is, is the is the party that’s paying for this incarceration, then it essentially then it’s essentially free money because the, the folks who are going to be hired are going to be local people who are going to be spending their income in local community, boosting the local economy.

And and those jobs are selling points that politicians across the country use when they want to get elected or when they, when they want to get reelected. And so on one hand you’ve got the private prison corporations that are profiting from this practice. On the other hand, you’ve got the politicians that are using immigration prisoners as a way of, of, of, of wooing votes.

Well, you call your book, your book is titled migrating to prison, America’s obsession with locking up immigrants, but it is under the umbrella it seems, and you draw some connections with America’s obsession with mass incarceration more broadly.

The, the immigration prison system that we have today was born in the very same circums out of the very same circumstances that the drug war mass incarceration system. That’s much more commonly known was, was, was born in the, in starting in the middle of the 1980s. And the, and the Reagan years when people of color were being, were being pinned as the, as the folks who were bringing drugs into our communities. And the very same legislative debates in Congress and the white house and the very same pieces of legislation that were adopted by Congress. We see not only that, the, the legal infrastructure that gave rise to the drug war mass incarceration was built. But at the very same time, the immigration prison system that we have today started it started to develop. And so these two things, these two things are our, our, our two, two ends of the very same phenomenon and willingness to lock up people, primarily people of color for, for committing sins that many of us commit and, and have the good fortune of not getting caught.

Well, people express shock and outrage. Some people express shock and outrage when Donald Trump, the candidate, talked about the kinds of people who were coming from Mexico. But your book documents that same kind of language all the way back to, well, I’m sure we can go even further back, but we’ll stop with the Chinese and how they were treated and viewed on the West coast. And the 18 hundreds History of, of demonizing migrants had, has been a part of the history of the United States for, for, for, for generations. It’s not new. It takes a different form. And, and one of the things that Donald Trump does is, is that he’s, he’s returned to that abrasive, explicit racism of the late 19th century. But, but, but, and, and that’s that, that’s lamentable too, to be sure, but I think it’s, it’s not okay to, to, to imagine Donald Trump as being, as being the, the unique human being, the, he imagines himself to be. The reality is that that the groundwork for the Trump administration was laid long before Donald Trump walked down. The, it came down the escalator in Trump tower to announces his, his presence, his candidacy for president of the United States.

Well, as we all know, except for the indigenous people who were, were here for 10 to 14,000 years before Europeans started coming. We’re all immigrants. I was thinking about my grandparents story. They came through Ellis Island. They were, they were held up for a little bit. They were central Europeans and they were Jews. I think about my, my mother-in-law’s story who came fleeing the Nazis. Also Jewish, couldn’t get into the U S ended up in in the Dominican Republic for four years. But her husband who was already her, her father rather, who was already here and had an established business, eventually got his family in. So in some ways, similar stories can be told except when it seems we come to the question of race. I mean, those, those Jews and those central Europeans were not considered white for a long time, but eventually they became white. Not the same case for the Chinese or for the Mexicans who lived along the Mexico us border. That’s that certainly is right. And I think that’s one of the thing w w the, the, the, the racial dynamics of immigration imprisonment, especially in the late 20th century and moving forward into, into today is what makes me worry that unless we have a radical, a re-imagining of migration, that will, will not only continue to see immigration and prison meant on a large scale, but that it will actually continue to increase rather than rather than, than, than, than shut down. One of the, one of the pieces of of, of history that I find most fascinating about this about this book that I learned while writing what putting together the book is, is in 1954 when Dwight Eisenhower, the war hero who had only recently been elected president decides that we should actually shut down the immigration prisons that remained Ellis Island being the most famous of, of those because it was situated within, within view of the statue of Liberty. You can have an ironic view of the statue of Liberty. And, and, and, and that came about because we stopped viewing these individuals as who, who were primarily from Europe, we stopped being them as, as, as a threat. And, and, and until we stopped seeing people of color in the United States as as dangerous, they don’t think we will ever get to a point where we get to revisit a period like we, like 1954 when the Eisenhower administration decided to shut down the immigration prison system that existed then.

But how successful was he in shutting it down over time?

Well, he, he, he shut down the largest immigration prisons that existed on the East coast and, and on the West coast. And so certainly it wasn’t, it he didn’t get to the point of absolutely abolishing the entire prison system. There were some folks, especially along the Southwest Mexicans who were still being detained on a short term basis. But we got as close as we ever have been. And I think I think in that history there’s something to be learned, something that is that, that we can use as as inspiration for, for crafting a a new path into the interference.

Well, I was struck by the facts that of the numbers of Hispanics, Mexicans and Americans of Hispanic descent who were lynched during the, you know, during the run up to the, to that era very much the same numbers you write as the number of African Americans that were lynched

On the, on a per capita basis. These were certainly different sized populations. But yeah, the, this was a, this was unfortunately, lynching fortunately was a, was a known phenomenon in the South West of, of the United States at the time in places like South Texas where I was, I was born and raised. And so the, the, the history of, of violence inflicted upon Latinos, Mexicans and others. In the United States, a, certainly not a new one. I think the immigration prison system that we have these days is just the latest, the latest of that state inflicted violence. But equally problematic. And, and, and, and it’s important too, to think of it not as be as occurring in a vacuum out of isolation, but as being only the latest version of this, that this, this preexisting pattern that goes back generations.

Let’s let’s talk about some of the people, the individuals. So as an immigration lawyer as well as a law professor, you, you come in contact with, with people on a regular basis. Who are some of the clients that that I don’t know either, either you can be specific or you can, you know, protect their names. But who are some of the people that you are thinking about these days and their, and their stock? Their lot?

That’s just a few weeks ago we celebrated veteran’s day in the United States. And, and like on that day, I can’t help but think of a gentleman named Jerry at AMECO who was born and raised in, in South Texas. Not very far from, from where I was. And our community was, is a fairly poor community, a heavily Mexican community. And when I graduated from college, I went off to, I mean when I graduated from high school, rather, I went off to college in new England and when he graduated from, from high school, he joined the U S army. And then, so he got deployed to Iraq where his job was to lead a, a group of, of tanks that patrolled through, through what was dangerous a territory. And while I was trying to acclimate to a new environment and the or, or Ivy league university that I was attending, he was getting attacked by people who were interested in repelling the, the U S army.

And one day his tank went over an IED and it blew the thing, the tank apart. And he was injured and he got sent back home. And unfortunately he didn’t get the care that he, he needed. And so he turned to drugs and as he was going through the criminal justice system, one day he just disappeared because ice had gotten ahold of him. And the reason I just got ahold of him was because he was not born in Texas. He was born in Mexico and he was, he has a green card. He’s been a lawful permanent resident for, for decades. And, and that’s what allowed him to be as American and, and in every way possible as in me, if not more so. But the sad reality is that when it comes to immigration law, what matters isn’t that he decided to put his life on the line for the United States.

What matters is that he was born just a few miles South of the magical line that we called the U S Mexico border. And that means that to immigration law and ice. He’s not one of us. He’s one of them. He’s in South Texas. He, his or the law firm that I’m a part of was able to get him out of, out of the immigration prison and and help him go through the we’re still helping him go through the immigration court process to try to fend off the, the government’s effort to, to the board him,

You know, you start this book also with the Diego Rivera Osorio a child,

A child who came to the United States. When his mother Wendy decided that life in [inaudible] was too dangerous for them to stay. And when they arrived in the United States, they immediately went up to a a border patrol officer and requested asylum. And within a few days they found themselves locked up in a Pennsylvania immigration prison. And the days went by. Eventually giggle won his case to stay in the United States. But it took 650 days of being confined in that Pennsylvania facility. A judge years later, a judge wrote that Diego had gone from diapers to this detention inside this facility. This is how we treat babies, infants. And not only that, infants who are going through the legal process exactly as Congress set it out. This, this is, this is truly troubling. And unless we have an enormous, the powerful reason to do this, I don’t think it’s defensible in any by any stretch of the imagination.

And, and just because we should note this the Trump administration has maybe increased the numbers of people who are detained this way, but the Obama administration pursued very similar policies

Live in the Obama administration operated the largest immigration prison system in the history of the United States until the Trump administration. That’s an important difference to be sure, but I don’t think it’s one that lets the Obama administration off the hook. The, the, what, what president Trump is doing these days is to ramp up. But w the, the, the foundation that president Obama set for him. And, and, and to be sure president Bush before Obama and president Clinton before, before Bush, that this is not, this is a not, not a, a policy that, that, that Donald Trump invented out of whole cloth. Certainly it is one that he has, he is exploiting two to wreak greater or greater havoc on, on more human lives.

All right, so what the people that end up in prison let’s talk about like who they are and, and then what they’ve done and where they go. Because you argue in the book that we can call these different things detention centers, but they’re all prisons and, and because people can’t leave. So what is the justification in current American law for locking up people who cross the borders without authorization?

The, the, the, the luggage. Two reasons. One is that you won’t show up for your court dates. And the second is you might endanger the public or the real, the, the reality is that we know how to, how to help people show up for court dates. We can first off start, we can start off by providing them with lawyers. Eh, we have, we, we’ve, we’ve piloted various projects. I’m going back to the Reagan years in which we have provided immigrants who are going through the, through the court process would access to lawyers. Right now there is no right to appointed counsel in immigration court, which is why most of the folks who are going through that process while detained are doing it by themselves. They’re doing it without the benefit of, of legal counsel. We give people lawyers the, the lawyer, one of the things lawyers do is obviously to identify claims that can be made to, to a judge, to, to find a way for this person to stay in the United States.

But there are also advisors, there are counselors. They, they help people understand the process and the more that people understand them process, the more they buy into the process. You pair the lawyers with social workers was other support services that makes sure that they have bus fare to get there. That they know and know where they’re supposed to be going and that they know what things that they need to bring an ID in order to walk in the door. That if if, if, if, if the car breaks down, their child gets sick, that they, that they have an ability to communicate with the relevant people so that they can change that court date and, and make sure that they are able to to, to abide by the process as, as, as Congress. Set it out for them. On the other hand, have the dangerousness factor is something that president Obama would wave around.

He said, my, my let me, I’ll paraphrase the speech he gave in and outside the white house in November, 2014 when he said, my administration’s immigration enforcement priorities, there’s to go after felons, not families as felons aren’t part of families, as a families don’t include felons. The reality is that we’re all mixed bag and some of us get caught and send them. Some of us don’t get caught. But, but if we want, we want to target people because of criminal activity, that’s what the police are for. That’s having, having ice, they’ll do the same thing. Is, is, is redundant at best. It’s disingenuous at worst because all we’re doing is, is, is targeting folks through two different law enforcement agencies for, for having the bad luck of, of, of, of of, of being somebody who’s not a us citizen.

But I also understand from your book that the, the felony, some people are committing or the aggravated felony, I think you said it’s called, is the act of crossing the border. Has that always been a felony in the U S

Crossing the border once is, is, is, is a, is a federal crime. It’s a, it’s a misdemeanor. Not, not a, not a felony. It’s been true since 1929. If you, if you in the United States, you get deported from the United States and then you cross back the United States without permission. That’s a felony. That’s a punishable by up to two years in prison, mint in the federal, in the federal prison. That’s also been a federal crime since 1929. But the reality is that we haven’t really prosecuted those prosecutors have gone after other activity that they think of as more serious. But that’s sort of the change in the in the late years of the Bush administration, George W. Bush administration when his administration decided that we ought to prioritize, so we should dust off these federal crimes and, and start to use them. And, and, and that remained true. And there president Obama, and it remains true now under president Trump where we are first the first criminally prosecuting people who are just coming to the United States without the government’s permission. And then we put them through the deeper, the immigration prison and deportation process too, for a second after the government to have a second bite at the Apple.

Some of those people staying in prison,

Most of those folks are, are getting in going in and out of the prison system fairly, fairly quickly. As they’re, they’re often sentenced to, to what judges will call time served better if the amount of time that it takes for them to go through the, through the conviction process. But we’re, we’re seeing averages [inaudible] that are hovering well above that as much as about 18 months. For, for some individuals it’s, it’s possible to get sentenced to many, many, many years, but, but the reality is most people don’t get Sentis to many, many years. They instead do a few months in federal prison and then they’re handed over to ice to be imprisoned while they’re going through the process of deportation. How long can that take? Well for Mexicans and, and it tends to, to be really fairly quick process, but for folks who have the strongest ties to the United States is a, and who or or that is, who have families here have been here.

And then it may take longer because they have an incentive to fight. And sometimes they may even have resources to hire a lawyer through family members who are, are working in the community and can pay for a lawyer. It also can take a long time for, for folks who are from countries that don’t have particularly good relationships with the United States. The the, in order to deport somebody, we actually actually get travel documents from, from the country that we’re sending somebody to. And there some countries that are pretty, pretty slow. I’m at to do that. And then, so it can, it can, it can even, it can take years in some, in some of the more egregious instances.

And and just just to bring us up to date, what’s the status of, or the numbers of separated children in detention right now? Do you have a sense of that? And also I guess families in detention right now?

Yeah. Right now we have three facilities. The, the, the federal government run three facilities that detain families together. Two of them are in Texas and one of those is in in Pennsylvania. That facility where Diego and his mother, Wendy were, were, were locked up. And, and, and I don’t know off the top of my head what the latest figures are on the number of, of, of families that are, are being detained.

That’s still happening. Oh, that’s still, that happens. It happens on a, on a, on a daily basis. Right.

All right. I want to, I want to take a step back, just one step back cause you were talking about how race plays into this and also how economics plays into this. So the Chinese that were on the West coast came over here to work on railroads and in mines and they were inevitably underpaid and then ended up at some point incarcerated on angel Island, some of them and being seen as the undesirable and illegal immigrants. And there’s also the history of the [inaudible] program, which directly affects the West coast of course, which recruited young men from Mexico to come pick the crops and then they were supposed to go back down when the seasons were over. Those people were also sort of a [inaudible]. They were exploited and they were also denigrated. And the same time they were necessary to the economies of the of the businesses that hired them. Right.

But that certainly is true. So we’re, so we’re the, the, the, the Chinese of course. So who were, who were key key in, in developing the, the, the railroads and, and there had been urban life and and, and culture along the West coast. But I think, I, I think it, it, it’s one of the frequent criticisms that we see of immigration prisons is that they, they, they, they remove people from, from the, the, the labor market when, when the labor market is what’s what is in many ways helping to, to bring folks to the United States. That’s certainly true. But I think one of the things that the that the immigration prison does it, that it could actually commodifies the human life inside the facility. Just, just like w we, we can do in, in other contexts as well.

That is if for every person who locked up the federal government is paying a daily rate to a private prison company or to local government and, and, and with that money people are being employed. Food is being bought. And and, and local economies, our, our, our become dependent on that, on that money. And, and, and so there is, there is not only profit to be made, but that economic dependency to be had by locking up migrants and and, and so, so that helps to explain it is that these, these facilities not only pop up throughout the country, but why it is that they are so difficult to, to shut down.

Well, well, well let’s talk, give me a minute to talk about the trends because we know that there’s xenophobia involved, nativism, racism, but early nineties, I was looking at some Pew numbers. I think it said that in the early nineties, there were about 3 million in the 80s, early nineties, about three and a half million unauthorized immigrants living in the U S by the middle of the odds was, or actually 2010, it was 12 million. Now it’s down to about 10 million. Do you think, if you agree with those numbers, do you think that the, the, the issue of immigration is also the fear people have of immigration is directly tied to the change in the numbers in the population increase?

I think it’s, it’s, it’s direct. It is so, so tied so much to the number of, of people as it is to the way that politicians in PR in particular use the, the, the the specter of immigrants as a tool for, for fanning latent fears and turning that, that, that fear into, into into votes. I think politicians have been incredibly adept at exploiting the, the, the history of racism in the United States to whoo voters who are already discomforted by the presence of newcomers or the thoughts of that newcomers might show up in, in, in their communities. And, and that is an unfortunate at is unfortunately a time honored tradition in the United States.

Well, but we will have a 440 million people in America by a, I forget that by when, but about 85 million will be foreign born. Now I’m making up. No, I’m think those are the right numbers, but I, I just looked at him and now I’m, I’m not sure, but I think that’s right. Or first or second generation. Does that matter? Does it matter if America has 400 million or 500 million or a billion over the next century?

People, I mean, in, in living in the U S

Yeah, I mean, cause that’s part of the argument people make, right? Well, I’m not racist. I’m not opposed to immigration. I just don’t want to see America. Have so many people that I won’t have the kind of lifestyle I want. I wanted the environment. I want you’ve heard, I’m sure you’ve heard all the, are you live in Colorado? I’m sure you’re that argument. Yes.

Colorado. And but of course I’ve only lived in Colorado six years, so I am one of those

False, right. You don’t count on us, right? Hey, I’m one of the people who’s targeted by that kind of language. I think it’s important to disclose

Personal stake and in that kind of a conversation do I think it matters? Certainly there’s a, this is an, this is, there’s a certain duplicity to, to those arguments when we welcome people from Western Europe and Canada and other wealthy countries, but, but tried to shut the door. Folks who are, who are coming from the global South people, people who look like me, Brown skin people, black skin people, poor people, people who are fleeing for their lives from, from political violence and gang violence from, from economic catastrophe. And I certainly also don’t, don’t, don’t take the, the, the, the, the, the, the point that I’m, I’m more morally upright simply because my mother happened to be in the United States when, when, when I was born. And somebody like Jerry [inaudible] his mother happened to be about about 10 miles South of where I was, where I was born.

If, if, if, if, if, if, if I merit living in the United States, it’s because I’ve committed myself to making a life here. I’ve committed myself to, to, to, to making a community of friends or family of, of, of I dedicate myself to, to helping my students become, become young professionals and, and citizens of our, of our democracy. And it’s not because I, my, my, my mother happened to be in Texas just like, it shouldn’t be it shouldn’t expose Jerry Amico to, to deportation simply because he, he he, he decided to join the U S military and got injured in the process and then we didn’t help him get this get the medical care that he needed. And so he turned to to, he made some bad decisions as a result.

So what are solutions in the long run? Because you know that there are candidates who say right now, candidates in the presidential election who say, we shouldn’t criminalize anybody who’s moving across borders, we should have open borders. Would it, would you support the concept of open borders, not just in the U S right, but around the world? Is that a feasible solution?

I think that’s something that we need to be talking about. I think it has to be part of the conversation. Look, I’ve, I’ve lived in, in, in, in parts of world where at one point there have been borders that have been heavily policed, if not by, by, by military, at least by local law enforcement agents. And, and yes, we can look at Europe where, where I lived in well I lived in the former Yugoslavia where at one point there were literally tanks and and, and snipers. And now there’s not even a stop sign. But we don’t have to look that far. We can look to Colorado and New Mexico at one point in the midst of the great depression as, as people were heading West from Texas and New Mexico and, and, and Oklahoma. The governor of, of, of Colorado actually sent the, the national guard down to the to the border with New Mexico and the border with Oklahoma to try to keep out people who, who they thought were coming here to, to work, coming here to, to take the jobs of, of Coloradans from places like New Mexico and Oklahoma.

We, we, we don’t do that anymore. That [inaudible] now still to our contemporary years, it sounds like like, like, like a like, like fiction. But the reality is we can build up borders just about anywhere and we can also choose not to build up a borders. And, and I’m hopeful that the conversation, the political conversation now will, will expand sufficiently broadly in the, in the era of Trump to, to, to ha give serious thoughts, serious consideration to the possibility of a radical departure. Because we know where we get when we do what we’ve been doing for decades. And, and, and that’s that’s profiting from, from human misery and, and, and, and that’s unacceptable.

What, if anything, should the United States do for the people who are fleeing for their lives or for better economic opportunity from El Salvador and Honduras and Guatemala?

I think we should do exactly what, what in our best moments we’ve given people the right to do that is to come here and ask for protection. Come here and ask for, for, for us to make a little bit of room and into, allow them to, to try to make a, a life just like we’ve been trying to make our lives for ourselves. We have in his eye O asylum system that’s in place. Lou, we should, we should pour resources into that asylum system to help the folks who are making those critical decisions to do so. Do so under the best circumstances. And we should we should help the folks who are, who are coming here fleeing for their lives, asking for asylum by, by giving them lawyers, by letting, letting them be working while they’re going through the process so that they can, they can support themselves, their kids can be in school and for starters they can be in the United States. So this process that we have right now where the Trump administration is basically shut down the border and force people to stay in the Mexican border towns that even though the U S state department this says are too dangerous for us citizens to travel to that, that’s, that’s absent, that’s unconscionable.

But what about the nations that those people are fleeing the cause? Those are also by the state department zone account unsafe. And we, you know, we, we we know that they are unsafe for many, many people who can’t leave. Is there some responsibility the U S has overall for those countries too?

Certainly the U S does have a, does have a role to play in, in, in helping to support economic development and helping to support the, the, and maturation of political democracies. And, and I would, I would be happy for, for the United States to, to do that. Unfortunately, the, the standard practice and us foreign policy has not been particularly rich when it comes to supporting young democracies. On the contrary, w w w w we, we are, we have a solid track record of supporting anti-democratic processes and most, most, most recently, the, the, the, the crew and, and, and believe, yeah, that we, that we have been supportive of just a few years ago, we sort of boarded a coup in Honduras. And and so I’m not particularly hopeful on that front. And instead I focus my attention on what I know best, which is how it is that the U S immigration system, including this Island system, can help the folks who do have the, the means and the, and the willingness to, to, to get to the United States, to get to our doorstep.

What, what a possibility do you think there is of actually dismantling this migration to prison system that’s in place now?

Look, when I was, when I was born, we, we hardly locked up anyone. Today I’m not yet 40 years old and we lock up almost half a million people. If we can, if we can build this system and in my lifetime, I’m hopeful that in my lifetime we can, we can tear it down.

Do you hear from any of people at the federal level who are with you on that and have proposed or even picked up some ideas along the lines that you’ve proposed?

If we’re going to start moving in that direction, we can’t rely on Congress who can’t rely on members of people who are currently elected officials to, to be carrying this banner. This is a, this is a long road. This is a difficult road is a road where I don’t know all the twist or the turns. And and which I certainly can do by myself and no member of Congress can do by, by herself or by himself. Cause I think this is, this is a conversation that needs to start at the community level. And, and then move up from, from there to the, the hallways of Congress.

So we’re back where we started with the citizen activists who are going down to those detention centers and protesting.

That’s right. That’s where, that’s where the true power lies.

CSR, our quality Moke Garcia Hernandez will be coming to our forum stage next Monday, December 9th at 7:30 PM if you’d like to join in the conversation or get a signed copy of [inaudible] book migrating to prison, America’s obsession with locking up immigrants, get yourself a seat. There is a link to the event in the podcast description below and if you can’t make it out but you’d still like to hear his talk, it will be posted on our civics podcast series. Well thank you for listening to episode 48 of in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle band EBU and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. You can listen to our full Townhall produced events on our arts and culture, civics and science series, podcasts. We also film and live stream select events on our Townhall Seattle YouTube channel. Just search Townhall Seattle and subscribe to support town hall. See our calendar of events or read our blog. Check out our website at town hall, seattle.org we’ll be taking a holiday break, but we’ll be back with more exclusive town hall interviews in January. Enjoy your holiday season ahead and thanks for joining us right here.