Artist-in-Residence Maia Brown reflects on what has brought her to seek out the multilingual and intergenerational histories of one particular anti-fascist ballad, and the unexpected places the song has taken her during her residency. During her April 13 Scratch Night, audiences will be invited into this wandering and unfolding story of one song. Here is just a sliver of that story.

I must have heard the song before, but the first time it stopped me in my tracks was listening to a Lankum recording. I had followed Radie Peat and Lankum’s work in the Irish archives for a number of years since living in Belfast and spending time with musicians adjacent to their project in Dublin. As I was turning toward archives of Yiddish song and struggle, I sensed a kindredness in Lankum’s approach to uncovering their own folk tradition with such careful attention to research. In interviews, Peat often reflects on what they know and don’t know about a tune — the many different iterations of lyrics and melody they have uncovered — and their approach to “filling in the blanks” of the story of a song.

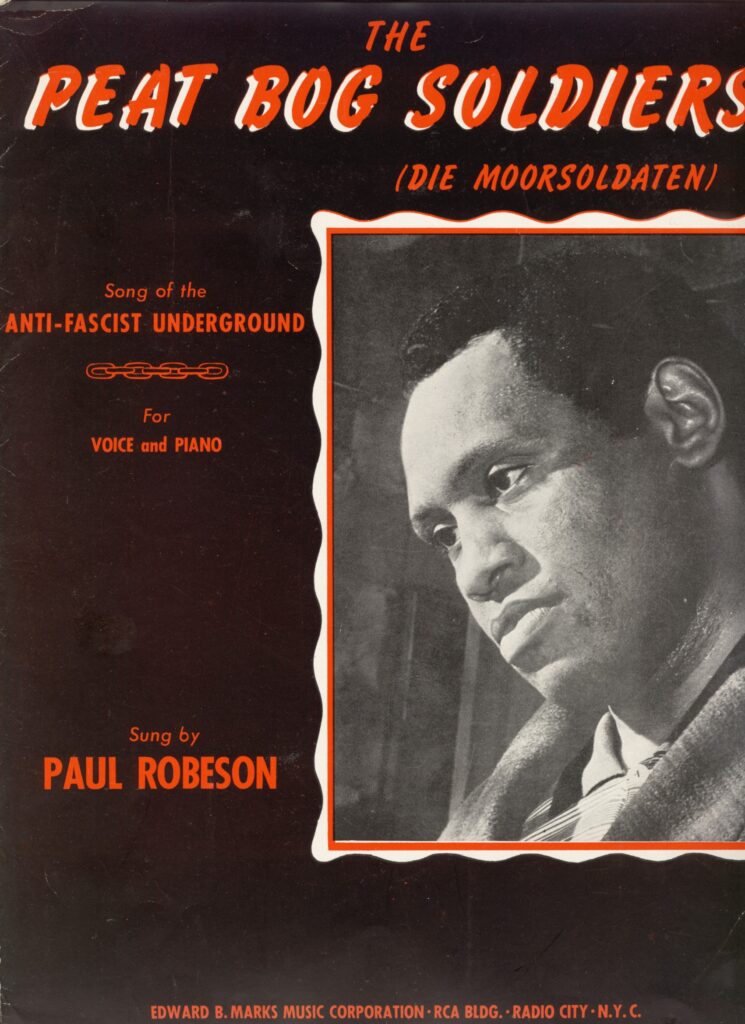

Lankum’s Peat Bog Soldiers is entirely a cappella, eerie and hypnotic. I thought it was an Irish tune for nearly a year —something in its sweet harmonic dissonance. It lodged itself in the part of my mind that demands to be hummed absent-mindedly and often in the interstices of the day. But, when I played the album for my father, he was surprised I had not recognized the song. He had first heard it from Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson’s performances of anti-fascist ballads sung by the International Brigades fighting Franco in Spain and knew that it had originally been written in German by inmates of some of the earliest nazi concentration camps built to imprison communists, union organizers, and other political dissidents.

For me, seeking the surprising stories that seem to stick to this 91-year-old song began then. Though I was hesitant to articulate why, I knew I wanted to sing this song. I knew I wanted to sing it in Yiddish. A year ago, I began, haltingly, to translate it.

The Town Hall residency changed all that. On the same day as my residency acceptance, I heard from a German archive devoted to the history of the song. They informed me that there already existed a Yiddish translation. I knew then that this was the story I wanted to share this Spring.

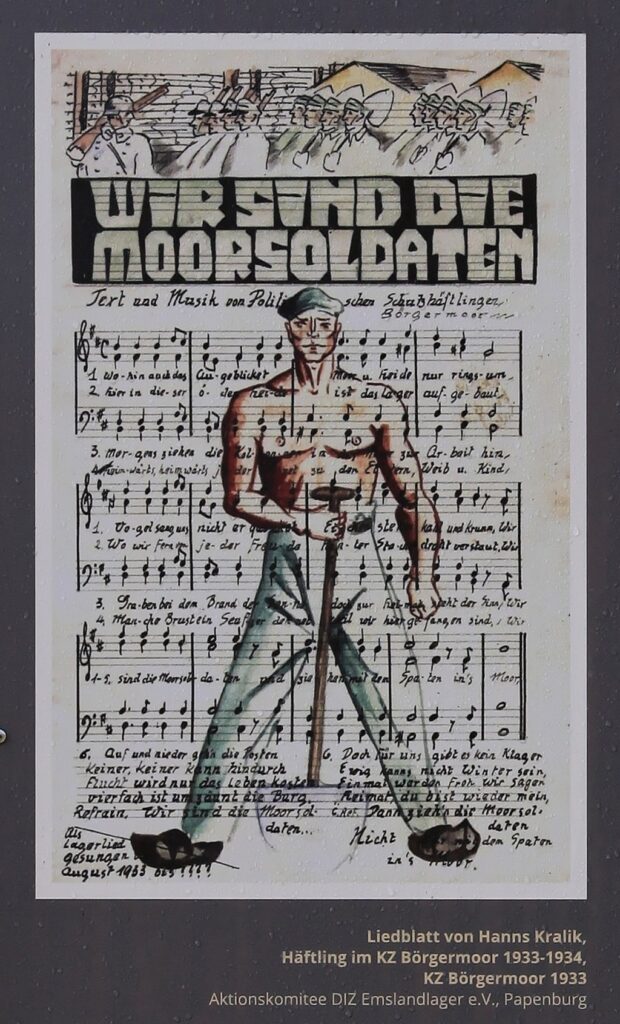

On August 27, 1933, after a night of beatings by the SS, the prisoners of the Börgermoor Camp — one of the first concentration camps built after Hitler’s rise to power in January of that same year — had negotiated permission for a camp-wide performance, what they called a “Zirkus Konzentrazani” (“Concentration Circus”). The event that prisoners developed was full of careful satire, depicting camp life and infusing seemingly banal performances with searing anti-nazi commentary. The afternoon program ended with a choir of prisoners singing the “Börgermoorlied” composed for the occasion — later known as “Die Moorsoldaten” or “Peat Bog Soldiers.” With the refrain:

Wir sind die Moorsoldaten

und ziehen mit dem Spaten ins Moor.

We are the bog soldiers

And we are marching with our spade; into the bog

The organizers and artists imprisoned at Börgermoor spent their days in forced labor, marching out of the camp with spades on their shoulders each morning to dig up peat and drain the surrounding wetland. The song imagines this prisoner’s trudge as a soldier’s march — reclaiming dignity while potentially undercutting the ideal of militarism simultaneously.

The song ends: “Winter cannot last forever, one day we will be glad to say: ‘homeland, you’re mine again.'” Then the final chorus makes a subtle and rebellious shift:

Dann zieh’n die Moorsoldaten

nicht mehr mit dem Spaten ins Moor.

Then will the bog soldiers

march no more with the spades to the bog.

That day, the prisoners and their captors sang together, but days later the song was banned. The song traveled mouth to mouth, camp to camp in prisoner transfers, and into exile outside of Germany when inmates were released. Sheet music was also smuggled out through family members of those detained during rare, monitored visits. The song shifted as it spread, versions found their way into handwritten concentration camp songbooks distributed in secret, including in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, into myriad languages sung by the International Brigades in Spain, and eventually on Folkways LPs in English translation…but when did the song move into Yiddish and why?

At the heart of my Scratch Night performance will be an attempt to tell some of the many stories that have sprung from this smuggled tune — some of my journeying through the many archives of this one song that began in German and now exists in dozens of languages. The evening will include our first performance of a Yiddish version of the song and an opportunity to ask what it means to seek out this song and to sing it in Yiddish. I continue to want to know more about what compels my own shifting relationship to this song as I invite others into the process.

Catch Maia’s free Scratch Night performance at Town Hall on Saturday, April 13 at 7:30PM.