In this week’s interview, Chief Correspondent Steve Scher talks with Dan Esty about solutions to big problems like climate change. Esty outlines ways to bridge political perspectives in order to approach climate change as a serious issue while maintaining flexibility when it comes to policy. He advocates for a structure of environmental protection policymaking that is more careful about balancing costs against benefits and adjusting the nature of the burdens placed upon businesses. Citing America as a nation that promotes innovation, Esty contends that we should overcome partisan hangups and present big ideas to combat climate change long-term.

Episode Transcript

This transcription was performed automatically by a computer. Please excuse typos and inaccurate information. If you’re interested in helping us transcribe events and podcasts, email communications@townhallseattle.org.

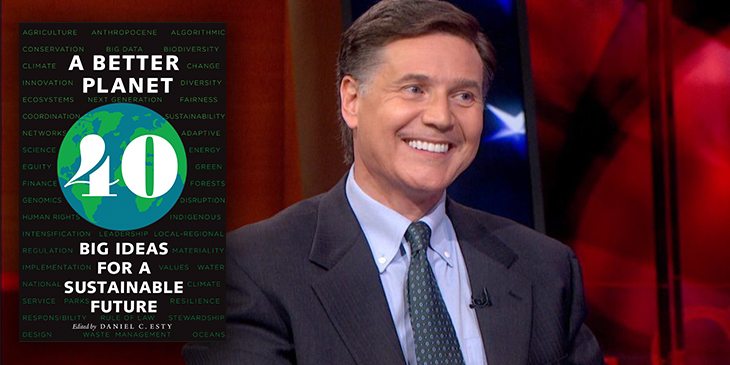

Welcome to in the moment a town hall Seattle podcast where we talk with folks coming to our stages and give you a glimpse into their topic, personality and interests. I’m your host, Ginny Palmer. Will people be able to build a future that is fair to all living creatures on the planet, just to all people and environmentally sustainable in the face of water scarcity, deforestation, mass extinction, pollution, and climate change? Do we have the political will? These are big and complex issues. Do we tackle them with big ideas? Daniel SD is a professor of environmental law and policy in a better planet, 40 big ideas for a sustainable future. He has collected essays from top environmental, economic and political thinkers in order to reimagine the response to these pressing environmental issues. SD brings his call for challenging conventional approaches to environmental policy to town hall at 7:30 PM on Thursday, February 13th, 2020 he spoke within the moment. Chief correspondent Steve, share over the phone.

Thank you for talking to me. First of all, my pleasure. I want to ask about big ideas, but I want to start with a small one that sort of is touched on in your introduction. I had an electrician here yesterday working on my a sump pump, and he was using tools and doing his math to make sure that he wasn’t going to electrocute himself and set everything up the right way. So we understood the value of science and facts. But at one point he said in our talk, well, I don’t believe in any of those theories. It’s all theories. And I knew what he was talking about. So I said, you’re talking about climate change, right? And he said, yeah, that’s right. It’s all theories. They don’t know what they’re talking about. And, and it just raises the problem of whenever you have a big idea or a small idea, you’re still confronted with people’s unwillingness to grapple with those ideas. And you talk right in the beginning about, part of the problem comes from the nature of environmental policy debate itself. Green groups, political allies have been many too many cases not taken seriously. The concerns voiced about the economic burdens, et cetera of environmental policy. But that sort of implies good faith on both sides. So how do you, what do you respond to when you have people of, you know, of the people you’re trying to convince who just aren’t going to be convinced? Yeah.

I think the reality is that environmental policy and environmental debates have become highly polarized and very partisan in recent years. And that is a big problem because when you’ve got that kind of, people aren’t interested in hearing about what the other side might say and, and aren’t really even interested in what the facts are. And I think one of the challenges of climate change, and I think it goes to the core of your question, is that the problem that is out there with those that are doubtful about the need to address the issue of climate change is not so much the science. I think actually, you know, as you point out in your story about the plumber visiting your house, it’s not that he’s ignorant of science to the contrary, makes use of it every day. And I think that most climate change skeptics are not really focused on the science.

What they’re concerned about is the policy response that might be required to the science. And I think in this regard, the, the issues fall on both sides. A good bit of what the environmental community has historically asked for what I might call their 20th century approach to problem solving seemed very heavy handed. It seemed very top down with a lot of government mandates, a lot of requirements that people do things in certain ways that for a significant part of the American political spectrum seems like a loss of choice, a loss of freedom. And frankly if there were to be a choice of having to do things in very specified ways that a big government agency was going to tell them or suffers from climate change, a fair number of people have, I think, come to the conclusion they’d rather suffer some climate change. And that reflects a need on the right to be more open to the issue as a serious one. And on the left to be more flexible as to what the policy responses might need to be.

You know, through this book and through a lot of the discussions about climate change, there is the phrase, this is an existential crisis which I take to mean that this is a crisis for our human existence, or at least the existence of our human culture as we live it. Now, why isn’t that enough for some money? Who has some thinking but says, Oh, it’s just a theory.

So I think the eye, so I think the idea that climate change represents an existential crisis is not a sufficient argument for someone who thinks that threat to existence maybe in the distant future, a 50 or a hundred or 200 years from now. And for many of those folks, they’re focused on the here and now. They face a real challenges in their lives, challenges about putting food on the table and meeting basic needs for their families. And I think a lot of those folks would say I’m, you know, worried about an existential threat in the future, but I have to worry more about what my family needs this week, next month and so on. And I do again think that one of the challenges of environmental policy and one of the reasons it needs to be fundamentally rethought in the next few years is that there’s been an inattention to the basic tradeoffs that are very real when it comes to how we advance environmental protections. It does require good policy does require care in what burdens are imposed on everyday people and frankly on business beyond that. And there is a cost to doing things environmentally sound ways and we want to make sure that it’s fully justified. And I think the existing structure of environmental law and the policy that flows from it has been sometimes inattentive to those burdens on everyday people and inattentive to the cumulative cost on society.

Give me an example from your own experience where it has been.

Sure. You know, I think we as a society have made enormous progress in addressing air pollution. And we have done a lot to clean the air in many places, but our clean air act says that there shall be actions taken to protect public health without regard to cost. And that then leads to a policy process that means that some things get done that makes sense and other things that are imposing costs way in excess of what might otherwise be thought to be reasonable or sensible in the circumstances. And I think we need us a structure of environmental protection that is much more careful about balancing costs against benefits. And we can’t assume that the maximum environmental answer to every question is the right answer for a society that also needs to provide jobs and economic growth and ensure that people can live good lives on their own terms not simply from an environmental point of view.

So, so again, is there a specific policy you can think of? Is there something in the automotive you’d go ahead.

We should rewrite our clean air act that says people should pay for the harm they cause. And it shouldn’t try to dictate the, each industry across the society specific pieces of pollution control equipment that they need to put on their smokestacks.

So in other words, except the externalities, but how you get there is to the contrary,

Reject the externalities, say that we are going to going forward have an end to externalities, at least unpaid for pollution harms that spill over onto society more broadly. And I think what we should say to every factory and to every source of pollution is that you can no longer simply get a permit and be allowed to pull it. We’re going to make you pay for every nontrivial increment of harm that you send up a smoke stack or out an affluent pipeline. And for the same, by the same token, we should say any business that has its business model, depending on extracting public resources, whether that’s water or the use of public land or the polluting of the atmosphere, all of that should be paid for too. So that anything that is an externality should be paid for

By the, by the polluter,

By the polluter or the user of the resource

By the user of the resource. So that’s what I meant by, except, I mean they have to accept the externalities. They need to accept the costs.

Absolutely. No society should not accept that. There will be extra analogies to the contrary. We should say that going forward there will be no extra analyses, at least not any ex finalities that aren’t fully paid for.

If that were possible, those costs would then end up somewhere down the line in affecting the consumer. Of course, right?

Well, it would affect the consumer, but it would mostly require businesses to be much more careful about how they produce. And it would ensure that when certain things that we now take for granted as low cost have their prices rise, it would be because there was a hidden cost to that seeming low cost. So when we buy a pound of hamburger and there is a, a, a hidden cost of the greenhouse gases associated with raising the cattle that produced that pound of hamburger it would not be right from a societal point of view to have us eat that hamburger without paying for the burden we’re causing to ourselves and to the planet.

Let me take you back to my electrician one more time. You know, we voted, we voted on a carbon tax, whether to put, impose a carbon tax in Washington state and it failed. It failed again. And when I asked him about that, I also said, well, what if the carbon tax [inaudible] you paid it, you as the consumer and so did everyone else up the line of production. But to make it cost neutral, which is the argument that we have, you get some rebate, you get some money back into your pocket. And that made some sense to him, but I wasn’t sure if it actually makes sense as a policy. So two questions. What do you think? And secondly is that the kind of discussions that need to head take place with the, with the skeptics, with the people who are feeling the brunt of anything that goes to reduce climate change impacts.

Yeah. So I think we absolutely need to have the conversation about what is the right policy path to take climate change seriously. And I think it’s a fair question for the skeptics to say can you construct a policy that allows me some freedom of choice that doesn’t dictate to me all the details of my life because you have a climate change agenda that needs to be advanced. And I think that’s a fair pushback from those on the side who are skeptical about action on climate change. Having said that, I think one can’t be both skeptical and then deny the underlying and real science of this. And my argument would be if we put a, a proper price on the causing of harm, which by the way is an age old concept. You know, we have an Anglo American tradition of law that says if you cause harm to your neighbor, you’re subject to legal action to compensate for that harm.

This is a 500 year old tradition of protecting in effect property rights. And I think what we would do by making people pay for the harm from their greenhouse gas emissions is simply a say. This is part of a longstanding structure of society that underpins what we know of and what we understand as modern America. And I would argue that in that regard we should make people pay for the harm. But I would as you were suggesting, rebate that money back to people in the form of other taxes being lowered. And I think that gives us the best possible chance to convince people that this is not a a, again, in the partisan world, we live in a hole set up, people are convinced this is really just an opportunity of government either accrue more power or take more money away from the public and to raise charges, raise taxes. And I think we want to make sure that the answer to climate change doesn’t seem to be falling into those kind of myths about what might be going on here.

Oh, my electrician friend was thoroughly convinced that all the science of climate change is being done by scientists who just want to increase their funding. And so make up statistics and studies and facts in order to prove that climate change is really happening.

That’s a mighty conspiracy that he has to spin up to have that be true. The diversity of scientists across not only the country, but the world is so great and the way want to achieve success in the academic world broadly in science in particular is by saying that what everyone else thought was wrong or by refining what everyone else thought. And so there would be enormous incentives for people to say, no, no, that prevailing wisdom is not correct. If it were true that were not correct. But the reality is that the overwhelming base of scientists come to understand this as a scientific reality. There are, of course, significant uncertainties that continue to be worked on and refined. And we know some things for certainty with a high degree of certainty about climate change. You know, the fact that we have a greenhouse effect is in dispute, indisputably true in fact, otherwise our planet would be uninhabitable cold.

The idea that the level of greenhouse gas emissions has risen substantially from preindustrial times has been measured a hundred different ways and again, is indisputably true. The projections about how fast climate change might occur, what the magnitude might be, what the regional distribution harms might be, all subject to some uncertainty. And therefore we have to be somewhat cautious. And of course, there significant uncertainties about the role of clouds, the role of oceans, and some other fundamental dimensions of the problem. So it would be wrong to say, and frankly, as some people in the climate change advocacy world do say that the science of climate change is is done. We know it all. That’s just not right. Science is of course, an ongoing process of discovery and refinement. But here’s what I would say. We know enough to know that we have a problem that needs to be responded to.

These are 40 big ideas for a sustainable future. You said that, you know, we have in the past tackle big problems with big ideas. What’s your, I guess, evidence that you see that we are able to tackle big ideas in this polarized climate?

So, you know, I think you’ve asked two questions that I want to pull apart a little bit if I can. One is do we have the capacity to bring big ideas forward to respond to big challenges? And I think that’s what America has done better than any country in the history of the world ever. We’re a society that promotes fresh thinking, contrarian views, innovation. And so my belief is that we as a society have stepped up to challenges, whether it’s civil rights or landing a man on the moon or creating the information technologies on which modern life now builds. We’ve done remarkable things when we endorse and and support and foster a spirit of innovation and fresh thinking. And that is at the heart of a number of these essays and the better planet book. And I do think we see evidence of that across many, many domains and it’s now time to turn some of those same forces of, of fresh thinking and creativity to our environmental challenges to the need for a sustainable future and most directly to the problem of climate change.

Now you added to your question, this idea that we’re in a politically divided moment and that is undeniably true and I think it does make the challenge of getting action on climate change and of unleashing these forces of innovation and creating the policy frameworks that structure incentives to engage the business community in helping find solutions. Quite a bit harder, but I think we’re moving towards a moment, probably not in 2020 but I hope in 2021 where there is a recognition that these are not democratic problems or Republican problems, but they’re American problems and they’re frankly planetary problems. And we really do need to bring people together. And one of the things that I would find and tell you that I am finding most heartening is the number of Republicans who I now see working on climate change programs and policies. And here at Yale got a number of students from the right side of the political spectrum who are deeply committed to conservative views on things like economic policy, but are working hard on a new structure of Republican environmentalism broadly and on climate change policy in particular. So I think there is a, a moment coming for people to get back together, to come across the partisan divide and to work together on a serious and thoughtful climate change strategy that can, a rally a strong majority of Democrats and some number of Republicans and move forward not at the left flank that some might want from the democratic side but up the middle with a broad base of support across party lines.

What are some of the thoughtful Republican concepts that those students are exploring?

Well very much I’m wanting to think about using market mechanisms and price signals to change behavior as opposed to government mandates and required investments in certain kinds of pollution control devices. So there would be a much greater enthusiasm, for example, for a an emissions charge on vehicles rather than a mandate as to what kind of cars or trucks people can drive. And I think that is the kind of thing that the Democrats could rally to that if we’re really making people pay for the harms, that becomes an enormous incentive to the auto industry to produce cars that pollute less and have fewer greenhouse gas emissions. And I think likewise, a similar structure of charges to industry would really provide an incentive not only for each company to think about its own practices, its own production process, and try to find ways to reduce the harm. It’s creating lower its greenhouse gas emissions profile, but frankly a big incentive to figure out how to do that, not only within your own business, but how to solve your customer’s environmental challenges, your customer’s greenhouse gas emissions problem, and therefore a big incentive for innovation in terms of the products and services that companies all across the country are providing.

What’s the government’s role in PR in an approach like that we’ve had in the past caps that shrink? That’s been the argument is that, is that the idea that government is there to continually ratchet down the amount that can be admitted?

Well, I think the you know, one of the fundamental policy questions is whether we go back to a cap and trade approach or whether we use straight out price signals, which would be a charge on emissions. I’m with those who favor the direct charge on emissions. I think it’s more transparent. It’s simpler. And frankly what it then requires of the government is narrower. The government needs to identify where there are harms and put some kind of a price on them. And frankly, with something like climate change where we’ve lived so long without a price on fossil fuel emissions and fossil fuel burning, my sense is that the key to success here is not just getting a price on the emissions, but probably to have it escalate slowly over time so that it’s not jarring to those that have made choices, including big investments in and buildings and infrastructure in factories and transportation strategies that depended on a certain set of assumptions about fossil fuels being at the center of our energy economy and of there not being a price on greenhouse gas emissions.

So I would favor, for example, a slowly escalating carbon charge that might begin at $5 per ton and then rise by $5 per ton per year for 20 years. Meaning that we’d end up with $100 per ton price on fossil fuel burning and the greenhouse gas emissions that come from that. But the initial years would be low cost, low burden, but it was standard sent a very strong signal all across the economy to anyone that’s building a new factory. Or thinking about a power plant or even buying a new vehicle that the time has come to think about how to get a low emitting a choice so as not to have to pay these rising carbon charges over time.

The costs the people who have sight, who, who look at this as well, the, they look at the prices being as high or even higher than that. Is there enough time? I mean, you’re talking about 20 years, is there enough time to do that and not a problem?

One of the interesting things about the escalating a charge is that it’s not jarring to people in the short run such that they fight to the death against the policy, but it does provide a very sharp signal. So if you’re building a new a factory, you’re thinking not about the initial charge of five or 10 or $15 per ton of carbon, you’re focused on the a hundred dollars per char ton charge that will be in place 20 years out, which is just the midpoint of your new facilities life. So it changes behavior dramatically from the very first year in terms of all choices going forward. And it’s really the choices going forward that we’re in a strong position to shape with this kind of incentive. And that is what I think is really critical is to get people off the dime into action and a breakthrough. What has been this political logjam where we’re not doing anything. And I think that’s what’s critical. Getting something done that in a reasonably quick timeframe sets up incentives for change behavior that begin to move people immediately towards the decarbonized future. We know as essential.

Let me ask you about some of the essays just in just touching on them and let me start with the ones that look at nature and wildlife and a resource extraction. Cause you have some folks towards the beginning of the book we talk about how we need rather than a siloed approach like protect a species, protect a tree, allow for drilling here but not there. And instead of an ecosystem approach that the authors argue could perhaps bring in extraction resources, road building control and the preservation of wild lands for the creatures that live on it. That’s a very, it’s a very proactive and a very organized approach. Is there, have we seen anything like that on the ground anywhere in, in Canada or America or the rest of the world that it tells you that this could work?

Sure. I think what we know is that the 20th century approach to environmental protection broadly and to land conservation and reach species management in particular was very fragmented. Environmental laws were siloed and that you’d have air laws in one area, water laws and another chemical management and yet a third and all of that wasn’t woven together into a coherent whole. So I think we do know that there are opportunities to be much more systems minded in how we construct our policy frameworks and how we construct our programs on the ground out across the country. And I think just to pick one example our regulation of pesticides has been done crop by crop and a product by product. And the end result is we’ve paid far too little attention to the cumulative impacts of all of the products that might be used out in in the food chain.

So I think we now know that it’s critical for us to having a healthy and safe food supply that we look cumulatively in a systems way across all of the exposures that someone eating food would face. And that leads to a different strategy about how we manage our land and how we encourage our farmers and ranchers to produce the food we eat. And I do think you’ve see a, a number of places moving in that direction. I think you’ve seen more of this cumulative approach in Europe. And I think we’re in America starting to realize there would be great benefits by being more a comprehensive in our approach to environmental problems. I think. And by the way, in the same regard we have to understand that our food supply is a, and the work of our farmers and ranchers is not simply a source of a problem, but it could be the source of solutions.

One of the critical things for success on climate change will be to think about the problem not only as a matter of emissions, but also as a matter of possibilities around enhancing carbon sinks. And green plants of course trees in particular are what is the greatest capacity for carbon capture carbon sequestration. And I think we’re now coming to realize that nature based solutions are essential to our success on climate change. So again, thinking comprehensively in a systems way about both emissions and the ability to absorb emissions through carbon sinks, it gives us a whole new perspective on how we’re going to address climate change and a, a very much a new perspective on the role of farmers and ranchers in being critical to success and not just a source of the problem.

There’s so many vested interests. It’s so difficult. I mean, yes, Europe is ahead in terms of systems, I’m looking at it through systems, but they are also facing the same but the New York times that called the insect apocalypse as the as the States are the insect apocalypse, the disappearance of so many insects, which we know we need for you know, the very farmers work to succeed in the end. So how do you, how do you get the good faith of the petrochemical industry or the, or the or the you know, the herbicide industry when they’re middle and short term goals go against these changes

You asked earlier about the role of government. I think the critical role of government will be going forward and this can be a redirection of substantial resources within organizations like the environmental protection agency, a focus on identifying harms of bringing the best science to bear epidemiological science, ecological science, to really map out with clarity in a way that we haven’t in, in our historical approach has been able to do, but increasingly can given the application of big data to our environmental challenges where harms are coming from. What the fate and transport of pollutants are, how they have impacts on both people and plants and animals. And then really use that to map out who needs to be held accountable and where there are severe impacts. We are gonna have the government still needing to set limits and prohibit certain kinds of emissions or certain chemicals being used and then really make people pay beyond that for the harms they’re causing.

And I think once those price signals are in place where people are really having to pay for the harm, they’re causing behavior will change. And there will be great incentives for technological innovation. And we have good examples of this already. The 1992 clean air act began to put a price on the chemicals that were damaging the ozone layer, the chlorofluorocarbons and that price was escalating year on year. As a result of that 1992 law. And within just a few years, all the industries that were using chlorofluorocarbons got out of them. They found substitutes, they created new alternatives. So I think that’s one example. The way we got a real attention to the acid rain problem that plagued our country in the 1980s was again, a price signal making people making power plants pay for their sulfur dioxide emissions. And setting a price on that cause those power plants to think hard about how to reduce emissions. In this case it was not so much technological innovation what fuels switching. They all realized there was an opportunity to burn low sulfur coal and that allowed us to cut in half acid rain precursors, the sulfur dioxide and, and NOx emissions that were causing harm to the lakes and forests across Eastern half of America and the Eastern part of Canada. So we do have good examples of where this kind of approach can make big change happen. At least out over time.

You have a couple of SAS who talk about, yes, big ideas are important and big change needs to take place, but we have to take care that we’re looking at the little changes and the incremental impacts. These have, they were talking about social justice in particular, they were talking about making sure that all groups are sitting at the table. How important are the little changes that they are talking about to the big ideas in your estimation?

Well, I think one of the things that really comes through clearly in this book is that you can’t focus on just the environment and not understand that there will be social impacts from changes in environmental policy, economic impacts. And we really have to think about this as a matter of environmental justice. We have several essays that are raising that question. How do we make sure that as we’re driving change, as we are addressing the pollution impacts that we know we have to take care of? How do we make sure that it’s not poor people or disadvantaged communities that end up bearing the brunt of that transition. And I do think one of the areas of climate change policy that has been least well developed over the last couple of decades is what’s required for a transition that doesn’t leave significant communities or industries or individuals behind. And we as a society have the capacity to invest in helping those communities reposition themselves, helping industries reimagine themselves, and helping individual workers move in new directions in new careers that will thrive in the decades ahead as rather than being under challenged because they’re linked to the burning of fossil fuels.

So I think that’s a critical set of essays in this book, a critical set of issues for our political community to grapple with. And you may also be making reference to the final essay of our, of our 40 in this regard. It’s in the spirit of an academic exercise, but one that I think represents a spirit that our society would benefit from, that we while advancing big ideas to try to create a pathway to a sustainable future, raise the prospect that big ideas may often fail. And so we’re being quite self critical at the very moment that we’re advancing these ideas and we’re saying to the world, big ideas and big solutions need to be understood in context. And if you launch a big idea but haven’t thought about the secondary effects of the unintended consequences, it may not get where you want to go. And so I think by being self critical, accepting that we have to be you know, with our approach to these problems with a degree of humility if they weren’t hard challenges, they probably would have been solved sometime ago. And I think that is one of the spirits of this book is to say, yes, there are pathways forward, but let’s think hard about what it’s going to take to succeed on those pathways and make sure we’re not leaving people behind.

Well, I guess what I got thinking about was the, the argument that there are many people in those communities that they’re being impacted who say, look, you want to make a change really fast. Let’s cite these polluting industries in wealthy neighborhoods. Let’s cite these these ideas, these impacts where they’re going to hurt the wealthy, not where they hurt the poor. And I mean that of course is a politically untenable idea, but only because who has the power? I mean it really isn’t in the end these big ideas don’t they depend on a kind of sharing of power that people are just not going to do.

Well. I think there are a number of essays that highlight that our current structure of the economy and of the kind of energy underpinnings of the economy are a reflection of past political choices, which are themselves are a reflection of the distribution of power, particularly political power. But I think we’ve also come to a point in society and this is one of the interesting kind of new lines of activity in the 21st century where there is a, a, a lot of focus on that distribution of power on disadvantaged communities, on concepts like environmental justice. And I think one of the things this book does is to say we need to take that whole line of inquiry very seriously and we are not going to be able to proceed with solutions that burden poor communities or individuals because it’s not right. And because we know that over time it would be inappropriate for our society to advance at the expense of those communities. So I think the, you know, I’m not saying that this book offers solutions to all of these hard challenges, but I think we grapple with them in a serious way and I hope it will provide a model for our society taking up these issues, debating them and taking seriously some of the new lines of thinking that I think have become part of our political dialogue in recent decades.

Well, your essay, red lights to green lights is all about innovation and incentivization. What’s your most when you look around, what do you see most hopeful about that aspect of grappling with these issues?

So I look around and I see a society that has just moved so quickly in a number of areas with the benefit of, for example, information technology. You know, there’s not a baseball team today that doesn’t pick players with a, a a, of statistics and data to underpin their choices. That’s very different than the, you know, world of 25 or 30 years ago where it was a tobacco chewing Scouts that told the general manager which players to pick. I don’t see a business across America today, particularly of any scale that doesn’t try to micro target its marketing efforts using data analytics to help drive that process. And I think what’s interesting is how untouched in general the environmental arena is by all of the information technologies that have transformed so many other parts of society. So I’m very excited about the marriage of information technology broadly and about a whole range of specific technologies from monitoring and metering to using metrics and using communications technologies and allowing for much more precision in how we take activities forward to give us a whole new world of approaches for environmental protection.

And I think that marriage of technology and innovation to environmental challenges offers a lot to be optimistic about it.

Daniel SD, professor of environmental law and policy and editor of a better planet, 40 big ideas for a sustainable future. We’ll be speaking at town hall on Thursday, February 13th at 7:30 PM. If you’d like to join in the conversation, get yourself a ticket. Thank you for listening to episode 53 of in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle baseband EBU and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. You can listen to our full town hall produced programs and speakers on our arts and culture, civics and science series, podcasts. Or if you prefer to watch instead of listen, there’s a whole library of content on our YouTube channel. Just search Townhall Seattle and subscribe to support town hall. Read our blog or see our calendar of events. Check out our website at town hall, seattle.org next week, our correspondent Venice behind. We’ll be talking with Tom Hartman about the hidden war on voting till then. Thanks for joining us right here in the moment.