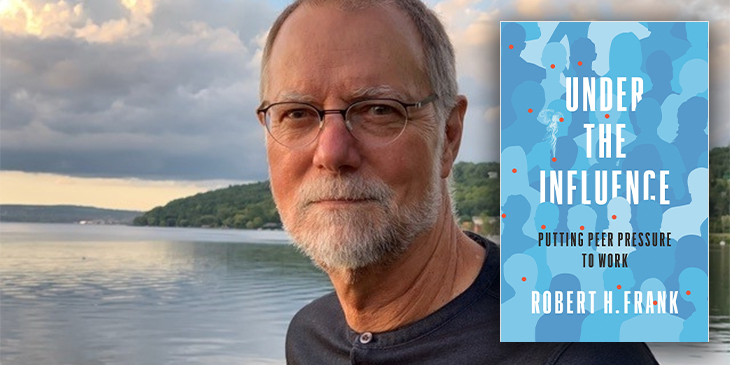

We’ve long known that our choices are heavily influenced by our social environment. Town Hall’s Alexander Eby sat down with Cornell University Professor Robert Frank to explore his new book’s message about how peer pressure can help combat climate change. Frank will be at Town Hall on 1/20. Tickets are only $5 (and free for anyone under the age of 22).

AE: At the core of your research is the idea of “behavioral contagion”—people adopting behaviors modeled by those around them. What are some ways this phenomenon can create problems for us?

RF: Here’s a simple example: We often cite secondhand smoke as the reason for our many taxes and regulations on smoking. But what we don’t acknowledge is that the far greater harm that arises when someone takes up smoking is to make others more likely to smoke. Behavioral contagion can act to our detriment, as with smoking, but also to our benefit, such as when installing solar panels or buying electric cars makes others much more likely to do so.

AE: Critics are skeptical of individual action to combat climate change, such as eating less meat, turning off lights, or buying more energy-efficient appliances. If we really want to solve the problem, they say, we need robust changes in public policy. You say that you once embraced those criticisms, but that your study of behavioral contagion has led you to a more nuanced view. Can you explain?

RF: Critics are right that without strong collective action, our efforts to combat warming will fail. After all, there’s not much tangible benefit for the planet if I recycle but nobody else does. But changing personal behavior has broader effects than many of us realized. Most importantly, it deepens our identities as climate advocates and increases the likelihood that we will prioritize acting on those values—voting for policies to fund green energy and knocking on doors to help elect politicians who will support those policies.

AE: Do you see a generational component connecting social influence and action based on environmental values?

RF: One clear split is the divide between younger and older voters. The former are far more committed to decisive action on climate change, and are more burdened by the practical consequences of inequality. Older voters are more prosperous, on average, and better positioned to oppose the large tax increases required for any serious effort to combat climate change and inequality.

AE: You say that opposition to more progressive taxation is rooted in a cognitive illusion—that, contrary to what most prosperous voters seem to believe, paying higher taxes wouldn’t require any painful sacrifices from them at all. Can you explain?

RF: No tax proposal on the horizon would threaten prosperous voters’ ability to buy what they need. But since higher taxes leave these people with less money to spend, it’s totally natural for them to worry about whether they could still afford the special extras they want. But because such things are inherently in short supply, the way you get them is to outbid others who also want them. And your ability to do that depends only on your relative bidding power, which is completely unaffected when you and your peers all pay more in taxes. The same penthouse apartments with 360° views end up in exactly the same hands as before. If enough people understood why higher taxes wouldn’t require painful sacrifices, progress in securing funding to face environmental challenges would suddenly become possible.

Join us on 1/20 to hear more from Robert Frank on harnessing the power of social influence to help build support for environmental policies. Tickets are on sale now!