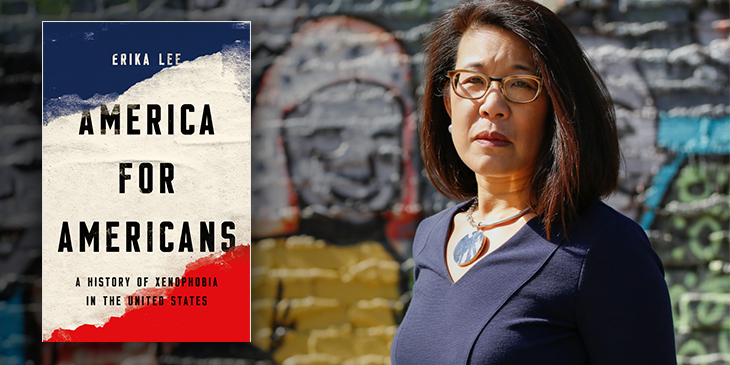

The United States is known as a nation of immigrants—but it is also a nation of xenophobia. Erika Lee,director of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, takes the stage at Town Hall on December 10 with an unblinking look at the irrational fear, hatred, and hostility toward immigrants which have been defining features of our nation from the colonial era to the Trump era. Tickets are only $5 (free for anyone under the age of 22) and are available now.

Town Hall’s Jonathan Shipley sat down with Lee to briefly discuss political power, racism, and Benjamin Franklin.

JS: What initially got you interested in the topic of xenophobia?

EL: I have always been fascinated with America’s history of immigration, one that has been marked by both a tradition of welcoming immigrants and a long record of xenophobia – an irrational fear and hatred of immigrants. But the 2016 presidential election and Donald Trump’s explicitly xenophobic campaign still took me by surprise. Then he was elected. My students, many of whom were first generation immigrants and refugees, asked me, “How did this happen?” I didn’t have the answers. I knew that I owed it to my students—and to all Americans—to try and figure this out.

JS: For the layperson, what IS xenophobia?

EL: Coming from the Greek words xenos, which translates into “stranger,” and phobos, which means either “fear” or “flight,” xenophobia literally means fear and hatred of foreigners. But I think that it is important to think about xenophobia beyond this literal translation. It is an ideology: a set of beliefs and ideas based on the premise that foreigners are threats to the nation and its people. It promotes an irrational fear and hatred of immigrants and demonizes foreigners (and, crucially, people considered to be “foreign” or outsiders). And it is a form of racism; it defines certain groups as racial and religious others who are inherently inferior or dangerous—or both—and demonizes them as a group based on these presumptions. When we think about xenophobia in these ways, it becomes clear that it is not only about immigration; it is about who has the power to define what it means to be American, who gets to enjoy the privileges of American citizenship, and who does not.

JS: As a nation of immigrants, why the paradox? Why do we fear the very thing we are supposedly proud of?

EL: This is one of the biggest puzzles that I try to figure out. The U.S. is indeed a “nation of immigrants;” a nation built by immigration. And while we have allowed generations of immigrants to come to the United States, that welcome has not always been uniform across groups; nor has it translated into full equality. There have always some groups that we have been wary of; to the point of demonizing them and labeling them threats to the United States and to the American people. Whom we have welcomed or banned has often been defined by race. European immigrants—while not uniformly embraced into the United States—have certainly faced less systemic xenophobia and discrimination than non-Europeans. When we understand xenophobia as a form of racism, this paradox, I think, is easier to understand.

JS: How does xenophobia work? Why does it endure? Who does it benefit?

EL: Xenophobia is often understood as something that rises and falls depending on what is going on in the United States. When our economy is good, when we are at peace, when we are unified as a country, we are more welcoming. When we are suffering through an economic downturn, are at war, or fractured as a society, we are not welcoming.

History shows that while economic and other concerns certainly help to make xenophobia thrive, it is not just an inevitable consequence of national anxieties. It is actively promoted by special interests in the pursuit of political power. It has also endured because it has been an indelible part of American racism, white supremacy, and nationalism, and because it has been supported by American capitalism and democracy. And it has succeeded through repetition. Targeting and discriminating against one group of immigrants makes it easier (and normal) to do it against others. Even as Americans have realized that the threats allegedly posed by immigrants were, in hindsight, unjustified, they have allowed xenophobia to become an American tradition.

JS: You note how Benjamin Franklin ridiculed Germans for being “strange.” Did the Founding Fathers have the thought that they could very well be “strange” to the native populations being immigrants themselves?

EL: In fact, it worked in the opposite way. America’s white settlers did not think of themselves as “foreigners” or “immigrants” in the same way that we use the terms today. They believed they were destined to possess and rule over the lands that became American colonies and the United States. They identified Native Americans and African Americans as America’s first “others;” those who were threats to the colonies and then the United States because they were unfit to American citizenship and racially inferior.

JS: Chinese exclusions, Japanese internment camps, the Muslim ban – we have a long history of negative treatment towards immigrants. How/why do we target certain populations at certain times? What are the ingredients to cause this hysteria?

EL: Xenophobia thrives best in certain contexts, such as periods of rapid economic and demographic change, war, and cultural conflict. This, in part, helps to explain why and how we have targeted Chinese, Japanese, and Muslim immigrants. The anti-Chinese movement spread during the economic recession during the 1870s; the incarceration of Japanese Americans and the targeting of Muslims in America happened during World War Two and after 9/11.

But xenophobia is also about racism and political power. Chinese, Japanese, and Muslims have all been portrayed as inherently more foreign, and thus, more dangerous than other immigrant groups. As such they have been targeted for racially discriminatory policies like African Americans and Native Americans. And the campaigns against them—especially the anti-Chinese and anti-Muslim ones—have been actively promoted by politicians as part of larger political agendas and as a way to mobilize voters.

JS: Are we making progress as a society to eradicate it?

EL: I’m sorry to say that at the end of writing this book, I am much less hopeful that I was at the start. The Trump era has revealed just how powerful and effective xenophobia remains in the United States.

JS: What can a citizen do to help in this regard?

EL: I believe that the first step is to understand how our anti-immigrant attitudes and laws have been steeped in racism then and now. In the past, we used explicitly racist language. Today, code words like “law and order” and “national security” obscure policies that are still racist in their intent and execution.

Another concrete action that we can all take is to remain informed about immigration issues and how immigration works so that we can be prepared to recognize “fake news,” mistruths, and distorted facts.

We also need to be resolved to the idea that solving xenophobia will not happen overnight. This is a much bigger and deeper problem than just electing a new president. It is deeply rooted in our worldview, our politics, and our laws.

Lastly, we can all get involved. There has been a tremendous backlash to Trump era immigration policies. If you agree that this administration’s approach to immigration is hurting, rather than helping our country, then let your voice (and your vote) be heard.

Hear Lee speak more about xenophobia at Town Hall on December 10. Learn more here.