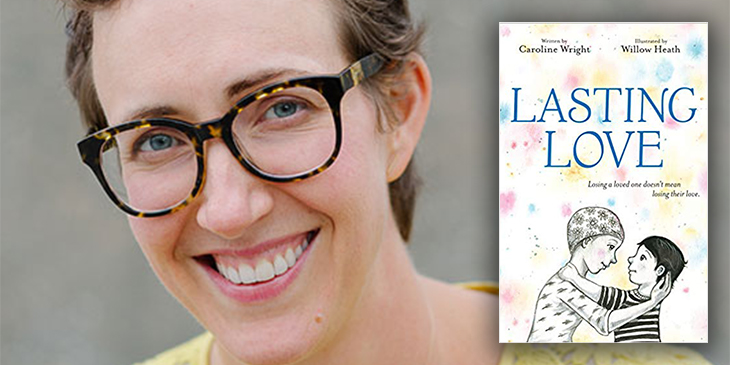

How do you talk to kids about death? Author Caroline Wright wondered the same thing when she was diagnosed with an aggressive, terminal brain cancer as a mother to her young sons. Now, having lived a year past her prognosis and written a children’s book to help children know the undying love of a parent, Wright will be at Town Hall on November 9 to help other parents find hope and agency with similar diagnoses. She’ll be joined by a panel of leading experts in the fields of children’s bereavement and cancer to discuss the complicated issue of what to say to our kids to comfort them when facing loss. Tickets ($5, and free for anyone 22 and under) are on sale now.

Town Hall’s Jonathan Shipley recently sat down with Wright to discuss honesty, science, and comfort.

JS: Tell me a bit about yourself.

CW: I’m a cook, writer and terminal brain cancer patient. After my undergraduate education in Paris, I completed the La Varenne culinary program with Anne Willan in Burgundy, then started my career writing and styling recipes as a food editor for Martha Stewart’s Everyday Food magazine that folded in 2012. While I was writing articles, I authored three cookbooks.

After I was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a very aggressive, incurable brain cancer, I shifted my diet and began writing personal essays regularly about my cancer as it relates to food on my blog. I also wrote a children’s book for my sons about my enduring love for them.

JS: What emotions swirled through your head upon hearing of your cancer in regards to your children?

CW: I had no idea how to help them process the news because I had no idea how to process it myself. It was a strange experience, to say the least, to be a source of comfort and pain simultaneously for my boys.

JS: How long did it take you to share with them the news? How did you go about formulating it? What were their initial reactions?

CW: My husband and I told them immediately. (Our engaged child at that point, really, was Henry, as he was four. Our younger son, Theodore, was only one; he was nonverbal at the time and still somewhat a baby.) We told Henry everything we knew, which wasn’t very much, as the situation developed. Henry was scared, of course, and struggled with the meaning of what was happening; his reactions would emerge randomly, out of context, when little bursts of understanding would break through. This meant that talking about my cancer was always an open dialogue, part of our daily lives.

JS: How have those reactions changed/evolved as time has passed for them?

CW: I don’t know if their reactions have changed, or if they have become more capable of expressing them over the time that’s passed. Henry seems to remain in a similar realm of understanding as when I was diagnosed two years ago; Theodore is a totally different being than before and is growing up in the presence of my cancer as fact. The biggest change I’ve noticed is Theodore’s expression of sadness surrounding things that happened at that time, like mentioning baldness or when his grandparents moved to Seattle. He understood far more than we thought he did at the time.

JS: Did your religious upbringing (if you had one) come into play when discussing death with them?

CW: My husband and I aren’t religious. We didn’t offer any sort of odds or hope or narrative of what might happen if I died, or lean on anything but fact. We just talked about love a lot, about how our connection is permanent regardless of the outcome, which feels spiritual in a way but not specific to a religion.

JS: Did scientific discussions come into play?

CW: Yes, more so than religion—we gave our boys developmentally appropriate answers, backed in what we did know. We only talked about the present, because that truly was all we knew in that moment (which is still true!)

JS: What ARE effective strategies in discussing/coping with death and grieving with youngsters?

CW: There are many—and the experts on the panel could probably speak to theirs—but for our family it was very simple: be honest and present, saying something rather than nothing. (Saying nothing is definitely scarier.) Providing outlets for our boys to maintain their schedules and connect with other people was helpful for our family, too. I don’t think there’s a right way to connect about death. And it’s a process, anyway—it’s not one conversation, but many. They change over time. The most important thing, I think, is just being there and being open, which is so hard if you are the one who is sick and is reckoning with death. For me, it was about holding optimism and reality separately, being very careful to know when to mix the two around my sons.

JS: What can we, as a community, do to help children who are dealing with death/grieving?

CW: Talk about it, out in the open. Silence from adults is what causes kids to feel alone in grief, when they are capable of understanding so much. Also, connecting kids with peers who are experiencing similar circumstances is incredibly helpful in knowing that they aren’t alone. People such as the experts on the panel at my upcoming Town Hall event are from a variety of outlets and are full of resources. Sometimes a peer can connect more fluidly than an adult.

JS: What do you hope people get out of your coming talk? Your new book?

CW: I hope to support families out there that were once like mine, facing uncertainty and pain without the words or understanding of what to do. From personal experience, I know the importance of language as it relates to death, and hope I can make it easier for other parents out there navigating their own trauma. I hope my book brings comfort to families facing the loss of a parent from terminal illness, but also to anyone who reads it a different loving perspective on death regardless of faith or creed.

JS: What’s next for you?

CW: Honestly, I don’t know! I am choosing these days not too look too far ahead; I try to stay present, knowing what a gift today is. I’m busy and doing a lot of things I love: writing, mostly; a lot of cooking; being a mom; making things that mean something to me, that tell a story and connect me to others. I’ve come close to the edge, seen behind the curtain, or whatever other preferred metaphor that communicates the limits of mortality, and I can tell you from the bottom of my heart that very little matters from that place. I try to keep that in perspective every day. I’m not on social media at all. Instead, I write a weekly food blog about my life now called The Wright Recipes, which helps give shape to what I’ve experienced in writing it. I also write a monthly newsletter that provides a space for those who want to keep up with how I spend my days, which has proven to strengthen my connections with friends, whether I know them personally or not. I’m grateful and alive and up next I hope is more of the same.

Join Caroline Wright and a panel of grief and bereavement experts on Saturday, November 9.