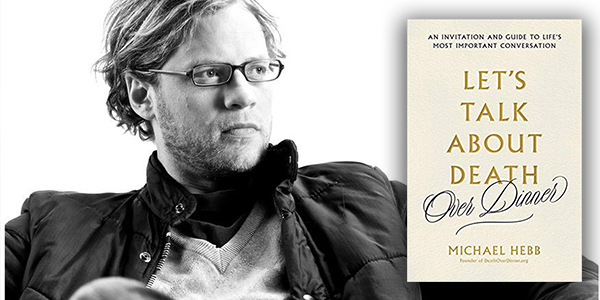

How do we want to die? Where do we want to be when our lives end, and what do we want to happen to us after we’re gone? It’s a topic we go to great lengths to avoid, from our hospitals to our homes. But for Michael Hebb, creating an environment for us to join our families at the table and have a conversation about the end of our lives is at the core of his work. Michael Hebb will be speaking on Town Hall’s stage on 10/11/2018 to explore ideas in his book Let’s Talk About Death (Over Dinner). He sat down with Town Hall’s Copywriter Alexander Eby for a deeper dive into the most critical conversation we’re not having.

AE: Your Death Over Dinner project is fascinating. Can you tell me a little bit about where it all started?

MH: For the last 20 years I’ve been gathering people to reinvigorate how we eat together and spend time together at the dinner table, and to make it as impactful as possible once we get there. In many ways we’ve lost the art and the knowledge of how to gather people at a table—not just go out to a fancy restaurant, but actually really use the table as a site of culture and engagement and joy.

This has ranged from bringing Presidents together—working with the Clinton Global Initiative and the Obamas—to working with people that are unsheltered or homeless or suffering from chronic illness. In these contexts we often work our way to the topic of death, and that layer has really morphed the table into a site of healing. Death Over Dinner was a way to get people back to the table to have this conversation and create healing on a larger scale, hopefully to reach millions. If we are our own best healers and our community is the second best, what are the tools for us to help deeply engage with each other and work on the issues that we repress?

AE: And the tool you decided to start with was something that’s commonly present in our homes. We can all get our heads around the idea of sitting down at the table with family or friends and talking over a meal.

MH: Right. Death Over Dinner was a way to cultivate a warmer and more inviting environment to have a conversation about this very complex and weighty topic of death. It’s provocative and it gets people’s attention, but in many ways our approach to death is very broken. 75% of Americans want to die at home and only 25% of us do. So when it comes to end-of-life, half of America is not getting its wishes fulfilled.

Often the reason for this is that people’s wishes haven’t been communicated in the proper way. Families don’t feel emboldened to honor those wishes, and they don’t know what decisions to make for a loved one when dealing with a tragedy or a crisis or a terminal illness. The cost associated with not having that conversation and not talking about death—you can’t even put a price tag on it. The number one cause of bankruptcy in America is medical expense, and the number one line item in those medical expenses is end-of-life expense. It’s literally bankrupting us to continue not having these conversations. Not to mention the emotional toll. If something tragic happens to your parents, your spouse, your friends, and you don’t know what they want, there’s such an additional emotional weight that settles if you’re not able to have these open conversations.

AE: I imagine you could learn a great deal about the people you’re closest to in your life by hearing from them what they would want their last wishes to be.

MH: I’ve never done a death dinner with a married couple that hasn’t said to one another “I’ve never heard that before,” or “I never told you this before.” In a good way. I’ve seen families build compassion and reveal hidden depths to one another. I’ve seen strangers become lifelong friends. We know it’s a critical conversation, but almost no one takes that next step with us, holds our hand or opens the door for us. I wanted to walk into these canyons and help people find the pathway, I wanted to take them through the labyrinth.

And I wanted my book to act as a guide us to start thinking about death and preparing to have this conversation in general. It’s meant to act as a resource to get people thinking about how to talk with the people we love, and also to look inward at our own lives through the lens of death. Death meditation has been around since the birth of philosophy, and is one of the best ways to actually identify how you want to live, to create your own personal mission statement for life. It’s the oldest, strongest medicine for knowing thyself and connecting with others—and it’s also practical as hell. It’s extraordinary that death, the topic we avoid talking about the most, has this much impact.

AE: When you say this is a conversation that we’re not really having, do you mean we as in all of everyone humanity or do you mean just American culture?

MH: Well, I can speak to a certain measure of authority that we aren’t having this conversation in the United States, but this is also true all over the world. In America, it was not until recently that doctors and nurses and social workers had an established code for end-of-life conversations. There’s an emotional weight that comes with those professions due to the fact that many of these doctors and nurses don’t have a healthy way to talk about the deaths that they’ve witnessed. There’s a very large percentage of our medical profession suffering from PTSD, with the highest burnout rate of any industry. There have been improvements, but we’re still at the very beginning.

And this isn’t a problem unique to the United States. I recently worked with the leadership of the Australian healthcare system, the Australian Center for Health Care Research. They discovered our initiative and reached out to us after they did a three year study which concluded that conversations about end-of-life would be the most effective way to improve healthcare in Australia. They were very clear that they had repressed the conversation, and as a result they did not have an especially robust system for living wills, power of attorney, advanced care directives—none of these notarized documents anywhere near the level they would have liked. I told them these documents are great and we should all have them, but it’s the conversations—the living, nuanced, personal conversations—that really help family members to know how to honor somebody or how to make decisions for them if they’re incapacitated.

AE: Do you recommend people organize their own Death Dinners?

MH: Having this conversation over dinner is the context that I introduced, but the book is meant to be for anybody. The goal was to increase people’s literacy and comfort around this topic and their ability to have their own end-of-life conversations with the people in their lives. You can have them in person, over phone, over E-mail. The project is for people who gravitate towards the comfort of dinner as a setting, to remove that barrier to entry. All you have to do is roast a chicken.