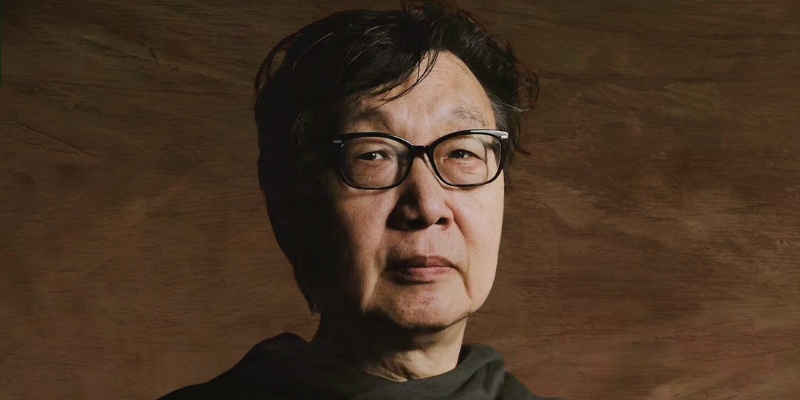

The island of Milos is beautiful. “What’s good enough for Aphrodite is good enough for me,” notes philhellene Mary Norris, the famed “Comma Queen” who has worked at the New Yorker’s copy desk for years. Corfu is a beautiful and civilized place, as well. Don’t get Norris started on the Dodecanese—the island group in the southeastern Aegean. “The sea there.” That’s all the words she needs to describe one of the most beautiful places she’s seen on earth.

Norris has had a lifelong fascination with Greece and the Greek language. Her new book is Greek to Me: Adventures of the Comma Queen. Norris will discuss the book, Greece, language (‘Signomi, then milow ellenica’ means ‘Sorry, I don’t speak Greek’), and the adventures she’s had there—amongst crumbling temples, olive trees, and ouzo—on May 1 at the Forum at Town Hall. Tickets are sold out but there will be a stand-by line at the door.

She first gravitated towards ancient Greece through movies. Time Bandits struck her. Jason and Argonauts did, as well. Ulysses. “I loved those movies. The minotaurs and gods and heroes.” She watched movies and read all the mythology. She grew to love the stories of the cyclops. The story of the Roman goddess Ceres, who turned men into pigs. Athena is her favorite Greek god. “She’s the goddess of wisdom. She never married. She was Zeus’s favorite, and she gave such good guidance.” Athena was also the goddess of war. She was known for her strategic skill in warfare. So fearsome she was born fully formed from Zeus’s forehead in full armor.

Athena

After Norris watched Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits, seeing a hunky Sean Connery as Agamemnon, she went the very next day to her boss at the New Yorker and told him she wanted to go to Greece. Her boss loved Greece and immediately took off the shelf a slim volume entitled A Modern Greek Reader for Beginners by J.T. Pring. The fact that her boss could read Greek at all astonished her.

Sean Connery in “Time Bandits”

In Greek to Me, she writes, “Seeing Ed unlock a Greek sentence gave me a Helen Keller moment: Greek could be lucid! It did not have to be unintelligible, as in the famous words of Casca in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: ‘It was Greek to me.’ Those letters could be penetrated, and here was the proof.” Having a lifelong interest in reading and writing—matching letters to sounds; building words; studying syntax and phonics—Norris discovered she could begin it all again with a whole new alphabet.

So she studied modern Greek. And then she studied ancient Greek. “The most beautiful letter in Greek? I like Xi. It sounds like KS, sort of like our X. Ooh, and also Omega.” The more she learned Greek the more she discovered how Greek, though exotic, is similar to English in many ways and has deeply influenced our own language. Greek, in fact, helped form English.

“It teaches you a lot about your own language,” she says of studying Greek in all its forms. “It’s also a link to the glories of the past.” A past where Homer wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey; where Constantine Cavafy wrote the beloved poem “Ithaca”; where Euripides wrote Medea. Norris delights that she can read them all in the original text. By reading Sappho’s words, or Herodotus’, or Socrates’, she brings them back to life—for language doesn’t die if it’s passed on to others. She’s thrilled to be that receptacle. The time of Odysseus and the mythic Trojan Wars are still present.

Something Norris says to Greeks living and long dead is one of her favorite words in their language, efcharisto (ευχαριστώ) (“thank you”). From it, we get the English word eucharist. “It has a beautiful deep meaning of gratitude and grace,” she says. To that, she raises a glass of ouzo to the lands of gods and poets.