On June 28 in the Forum at Town Hall, acclaimed author Charles Fishman will illuminate us on America’s impossible mission to the moon. It’s the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing and his book highlights the behind-the-scenes heroes that helped put men on the moon. Get your tickets now.

Town Hall’s marketing manager Jonathan Shipley sat down to talk with Fishman about Gemini space walks, sneaking onto lunar modules, and how many hours of work it took to have Neil Armstrong stand on the moon.

JS: You were alive for that first moon landing. What are your memories of it? When you were a kid were you interested in space, science fiction, and astronauts?

CF: I was eight years old when Apollo 11 landed. I grew up in Miami and paid a lot of attention to the space program and I certainly watched the first moon landing. I remember watching subsequent ones, I think even once at summer camp. We all jammed into a room with a black and white TV.

When I was a kid I built Saturn Five rocket models and lunar modules, spaceship models. I still have some of them. I have a Hanna Barbera album of the first Gemini space walk that I listed to a lot when I was a kid.

I never wanted to be an astronautI loved learning about the people that made it happen. The astronauts are the very public heroes of those missions, but I liked knowing about all the people that helped them become those heroes.

JS: And that interest stuck with you all these years.

CF: I was a Space Shuttle reporter for the Washington Post during the Challenger accident. I covered the Challenger full time for six or seven months starting the day of the accident. I went to Houston for it. They created a media center for the 40 or so reporters who descended on Houston after the accident in that main building. And I sat next to a guy named Howard Witt from the Chicago Tribune. We worked late and, you know, talked a lot. And there was a lunar module adjacent to the press center. We debated endlessly over whether we should just skip over the fence between us and the lunar module and look inside. If we did they might take our press credentials. Or should we ask permission and risk being told no? In which case we couldn’t even sneak up because we’d already been told no.

I finally asked someone. Can we see the inside of the lunar module? They said, sure, let’s do it right now.

JS: And it made an impression?

CF: It was a real lunar module and me and Howard got to climb up and sit in the cockpit! The Challenger disaster was caused by NASA failures. The Challenger was human or bureaucratic error, start to finish. All those people should not have died. And then I was in the lunar module from the era before that and it worked perfectly.

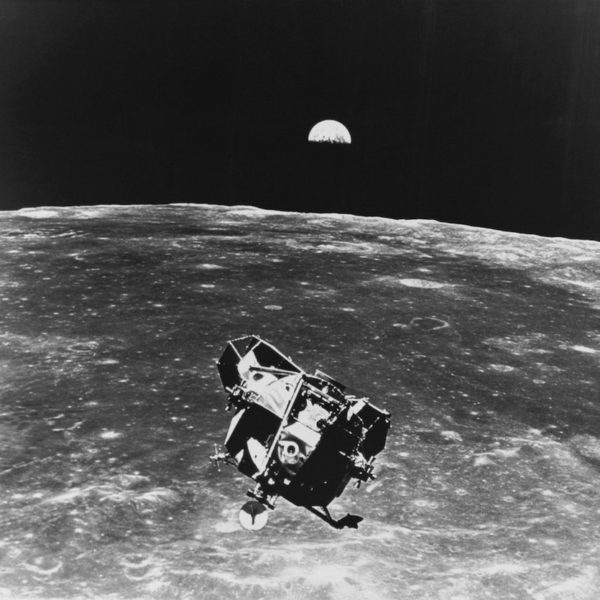

JS: I watched that recent Apollo 11 documentary and was amazed at how ridiculously archaic the spacecrafts looked. The little buttons and gauges. It’s mind boggling to me that they made any of it work.

CF: That’s an important distinction to make. Based on the surface of things it looks archaic but it was advanced technology for the moment it was in. It was also bulletproof. Reliable. The computer that flew the lunar module had less computing power than your microwave oven—but you wouldn’t let your microwave fly you to the moon. A single iPhone has more computing power than all of the computers that NASA had available during any given Apollo mission. The people programming that lunar module knew how to stretch their computing resources to the absolute max.

Nothing failed. The spacesuits were perfect. The lunar modules were perfect. The computers that flew them were perfect. There was not one problem in 100 days of space flight.

JS: Tell me a bit more about those computers and the technologies of those days.

CF: The software for the computer was programmed using actual wires. There were no memory chips. And the computer memory was woven by hand by ladies sitting in Waltham, Massachusetts or the Raytheon factory.

Also, the heat shields for the spacecraft required material that had never been created before. They invented these materials and then injected them into the craft using caulk guns. They had limits, but they had to exceed those limits because it’s what they had to do.

JS: When you were researching the book, what were some of the more jaw-dropping facts for you?

CF: I didn’t realize how much had to be done by hand. The blend of high technology with handiwork is incredible. I did some math and found that there were 2,500 hours of space flight. I did a rough calculation of the number of work hours to make that happen. It turns out for every hour of space flight it required 1 million hours of work on earth. A million hours of work is literally the work lives of ten people. So, every hour of space flight required the equivalent of the entire working life of 10 people.

There were a total of 11 missions. You had 400,000 people working to put 33 crewmen in space. It was a daunting undertaking.

JS: Any surprises in your research?

CF: I was surprised to discover that at no point did even 50% of Americans say they supported going to the moon. We have this image of it as an incredibly popular undertaking. 94% of American households watched the first moonwalk. But there was never a majority of Americans who thought going to the moon was a good idea, or that it was necessary, or that it was worth the money. It was all political leadership and political will.

JS: With NASA doing the impossible, did that stir other industries to try and do the impossible as well?

CF: That’s an argument I’m making in this book—the impact NASA had on society. NASA laid the foundation not for the space age but for the digital age. That iPhone in your pocket is possible, in part, because of what those men and women did back then.

JS: Should we go back to the moon? There’s been some recent discussion of going back of late.

CF: I think for the money we spent on Apollo, what we got back on earth paid us back a hundred or a thousand times on the dollar because Apollo helped unlock the digital revolution. We only spent $20 billion going to the moon in actual money. There were individual years of the Vietnam War that cost more than the entire moon mission. So, I’m all for space exploration and for human space exploration, but it needs to serve a purpose. Should we go to the moon by 2024 to just walk around? No. I think we should go to Mars. Maybe learn the lessons of living on another planetary body.

JS: Do you want to go to the moon?

CF: I’m 58 and I don’t think I’m going to the moon any time soon. Maybe soon we’ll be in an era of human space travel, but not quite yet. Maybe in 15 years. I think what Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are doing are steps in the right direction.

Take steps to see Fishman at Town Hall on June 28. Tickets are on sale now.

This event is part of Seattle’s Summer of Space, a city-wide celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first Moon landing. Celebrate at the ONLY place in the world hosting the Apollo 11 command module Columbia during its 50th anniversary year: The Museum of Flight. Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission runs at the Museum of Flight from April 13 to September 2, 2019.