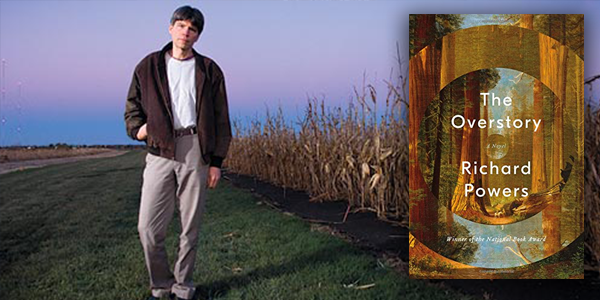

An Air Force loadmaster in the Vietnam War is shot out of the sky, then saved by falling into a banyan. An artist inherits a hundred years of photographic portraits, all of the same doomed American chestnut. A hearing- and speech-impaired scientist discovers that trees are communicating with one another. These characters and their struggles exemplify the sweeping, impassioned story of activism—and stunning evocation of the natural world—that is author Richard Powers’ twelfth novel, The Overstory.

Town Hall’s Alexander Eby talked with Powers about where his idea for the novel originated and why trees, specifically, are important to telling our complete story.

Buy tickets for Richard’s talk on Tuesday, April 24.

Buy the book: The Overstory

AE: I’m curious about the overall premise of your novel, The Overstory. The overarching throughline seems to be the presence of trees and their relationship to the characters. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

RP: I suppose that’s the easiest way to describe the common denominator of this story. It’s about nine people with very different personalities and very different histories, each of whom for different reasons must come to take more seriously the invisible presence of these enormous long-lived creatures. But beyond trees, I guess it’s a story that asks how to dramatize the relationship between humans and non-humans—how to raise this question of what it would take for us to live here on this Earth rather than be constantly fleeing into one that asks the rest of creation to live on our terms.

AE: So more than just trees in that sense. The whole of nature.

RP: I used trees as an entry point into this broader question of people coming to terms with the world beyond the human. So much of the book has to do with current research that’s revealing all kinds of unexpected aggregate behavior among trees, for instance, their ability to communicate with each other via chemical signaling in semaphore. It just seems another fresh way to talk about this endless challenge of people in a world that is increasingly hard-pressed by our relegation of the rest of creation to the role of mere resource.

AE: It’s fascinating to see what we’re discovering regarding research on the behavior of trees. It’s just difficult for us to observe given that this all happens in such slow motion relative to our own lives.

RP: Yes, the research is proceeding in a lot of different directions. The roots of trees are connected underground by fungal filaments, and the exchange of hydrocarbons and sugars between the tree and the fungus, and the reciprocal nurturing of the tree by the fungus produces what Suzanne Simard, one of the leading researchers in the topic, calls the “Wood Wide Web.” It forces us to think of the forest as something that emerges out of lots of individuals, deeply connected in webs of cooperation.

To me that story—the discovery that these other enormous creatures have agency and memory and social connections and complex behavior—compels a rethinking of who we are in connection to these other entities. All of that compels a rethinking of who we are in connection to these other entities.

And that’s kind of an odd program for literary fiction. Traditionally, contemporary novels don’t venture much beyond the psychological or the social. The stories that we tell these days are almost exclusively about us. We fascinate ourselves. We pay attention primarily to the social relations among people, to the tensions inside our own psyches.

AE: Is that why you chose to situate this in a novel format? As fiction?

RP: The stories we tell about who we are, the stories we tell about what non-humans are. They need to be informed by all of those concerns that are traditionally the arena of non-fiction, but they need to have the heft, the emotional impact, and the visceral quality of fiction. We are entirely dependent upon plants, biologically and culturally. They should be at the heart and soul of the story that we tell about ourselves. It shouldn’t be a separate domain treated specifically and exclusively by scientific or non-fiction writers.

AE: And it seems like your representation of trees at the center of this story is aiming to redefine what we imagine a character to be.

RP: We have been almost entirely colonized by a way of thinking that I sometimes call “individual commodity culture,” where meaning is exclusively the domain of the self and life consists exclusively of individual people introspecting, coming to terms with their own conflicting values and making peace with others around them. At this point we believe that life is this simple struggle between ourselves and our immediate friends and family. And that’s as far as the story goes.

It’s difficult to understand that most people who have lived in human history didn’t have that assumption. That for them, meaning was out there. It’s tough for us to think of meaning as anything other than a subjectively negotiated thing.

AE:Is this story the spurred by any meaningful personal relationships with nature or specific trees at all that you can recall?

RP: Until six years ago when I first began to think about this project, I was as blind to trees as anyone. I mean, I saw them, I appreciated them aesthetically, but they didn’t particularly seem to have their own urgency. It was really first experience of a Redwood forest that began to challenge that. I think a lot of people have that when they see Redwoods for the first time; there’s something so majestic that you can’t be blind to them in the way that you are to plant life so much of the time.

Once I saw a Redwood forest as something more than a resource or aesthetic diversion, I returned to the forests of the East where I grew up and began to see the trees of my childhood for the first time, just to look at them and to understand all of the incredibly complicated shapes and forms and structures that they create. I had, again and again, this experience of coming back to the forest of the East while writing this book and saying to myself, “I had no idea.” I never—I had never seen it.

AE: I can imagine visiting forests you grew up with and seeing trees that you saw as a child, coming back to them years later. And it’s the same tree, the same organism.

RP: But everything’s different because something had changed in me. I began to see what had been largely invisible to me up until then. And I guess that’s my hope for this book. I hope that the reader has that experience of being un-blinded toward these incredible creatures in their own street or deeper into the woods as far as they want to go—that experience of perpetually saying “I never saw that before. I have to look at them now with new eyes.”

AE: It sounds like a lot of native Seattleites will be inspired to take a trip to the Grove of the Patriarchs after reading this.

RP: Or even to see the urban planting in a different way. To understand the richness and diversity of street trees. It’s a great place to start.

Buy tickets for Richard’s talk on Tuesday, April 24.

Buy the book: The Overstory