In this week’s interview, former Town Hall Artist-In-Residence Erik Molano talks with Peggy Orenstein about the fraught emotional landscape and difficulties faced by modern adolescent boys. Orenstein outlines the harm our society does to teenage boys by pressuring them to suppress their emotions, cultivate aggression and dominance, and glorify sexual conquest. Molano and Orenstein delve into the complications of pornography, and how the images and narratives it presents are skewing young men’s understanding of sex and teaching them to model relationships that are unhealthy and emotionally toxic. Orenstein calls for a collective cultural shift to help young men break down these social constructs and reconnect with sensitivity, emotion, and healthy sexuality. Get an insider’s look and stay in the know about what’s going on in this moment at Town Hall Seattle.

Episode Transcript

This transcription was performed automatically by a computer. Please excuse typos and inaccurate information. If you’re interested in helping us transcribe events and podcasts, email communications@townhallseattle.org.

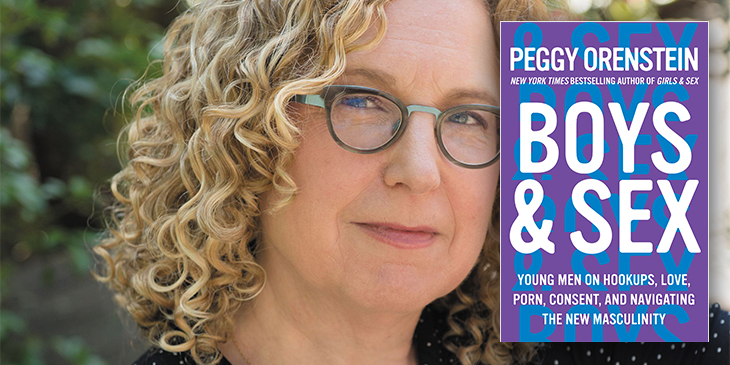

Hello and welcome to in the moment a Townhall Seattle podcast where we talk with folks coming to town hall and give you a glimpse into their topic, personality and interests. I’m your host, Ginny Palmer. We’re already into our third week of January, 2020 and MLK day is around the corner. We have a few events in celebration of the holiday including an annual Martin Luther King jr celebration on the 16th and ascribe called ques talking with Nikkita Oliver about dismantling our colonial legacy on the 17th you can find out more about these events and many more on our calendar at town hall, seattle.org how do we treat young boys differently than girls and how do these entrenched gender norms affect the landscape of men’s emotions and relationships? On January 23rd and New York times bestselling author Peggy Orenstein is talking to a sold out crowd in our forum about her new book, boys and sex, young men on hookups, love porn, consent, and navigating the new masculinity or correspondent for this episode. Eric Milano is the founder and creator of photon factory, a Seattle based design studio and community space. As a former town hall artist and resident, he curated an event about toxic masculinity back in 2018 and has been involved in organizing local male centered events with missions related to consent and supporting the rise of a new masculinity as wholehearted men. A warning that there is some strong language used during this interview.

In your book you mentioned how neurologically there really isn’t that much difference emotionally between infant boys and infant girls. But how do adults treat infant boys differently than they do, let’s say with infant girls?

Yeah, you’re absolutely right. There is no kind of innate, um, difference in capacity for empathy or any for emotion. There’s even some evidence that, um, infant boys are, uh, kind of the more emotional sex, but from the get go, um, boys grow up in an impoverished emotional landscape compared to girls. So there’s a classic study where, um, uh, adults are shown a video of an infant that’s surprised by a Jack in the box. And if they’re told beforehand that the child is male, they think that the child’s reaction is anger and not surprise, not frustration, not fear gotta be anchor. And mothers of young children have repeatedly in research been found to talk more to their daughters and to employ a broader, richer, emotional vocabulary, um, than they do with their sons. And again, with their sons, they focus primarily on one emotion, anger. So there’s this kind of immediate funnel of a whole bucket of emotions, of human emotions, um, that, that are funneled into this one. Um, emotional of anger for boys that they learned that that’s going to be their go to happiness. They also get happiness.

Yeah, that’s really fascinating. Sounds it sounds almost like the parents are projecting onto their children soon after they’re born.

Well, we socialize our babies from birth right. And our ideas about, um, gender and gender performance and um, what boys are, what girls are, how they should behave. You know, we, we all carry those two, um, and into our parenting and especially if we don’t, you know, do a lot of work to examine them. And even if we do do a lot of words or examine them, we still carry them into our parenting. So I really want him with boys and sex to be able to, um, you know, it’s mostly about teenage boys, but really kind of look at, uh, how the culture and parents and media and all these different forces peers, um, play into boys socialization and create this idea of masculinity as well as then, um, how that affects their personal relationships and the people that have those relationships with.

Yeah, definitely in boys and sex. You mentioned the man box, um, that they are, the boys are taught to disconnect from feelings, shun intimacy and become more hierarchical in their behavior. Can you talk more about the man box or this idea of what men are supposed to be?

Yeah, it was really interesting when I was talking to teenage boys, you know, on one hand they, you know, a lot of change for them. They saw girls as equals in the classroom or equals, you know, in leadership or um, in, you know, worthy of their place on the playing field. All of that. They have female friends, they had gay male friends. Um, they may have trans friends even, but, uh, but when I would ask them, what’s the ideal guy, you know, then it was like they were channeling 1955 and they would say, you know, athleticism, um, being dominant, being aggressive, uh, and sexual conquest. And the big one was stoicism, you know, emotional suppression and guys would talk to me about having learned to have built the learn to build a wall inside of them. Uh, taught them to train themselves, not to feel or train themselves, not to cry.

One boy said that he couldn’t cry. Um, so he had trained himself not to cry. So when his parents got divorced, he streamed three Holocaust movies back to back. And you know, that that did the trick. Um, but, uh, but, but what I felt was at the very heart of this book, at the very heart of boys and sex is boys wrestling with not just the parameters of the man box. Yes. Um, and that’s not my phrase, but, um, but also with vulnerability in this really fundamental and what it meant to be emotionally vulnerable and the temp brew against the vulnerability. And denying it and um, deflecting it and rejecting it and embracing it. And I could think of, you know, human emotional vulnerability is a fundamental aspect of being human. And even beyond that, no Bernay Brown calls it the secret sauce to attaining and sustaining relationships. So when we cut boys off from their ability to be vulnerable, when we tell them it’s not allowed to them, you know, we’re really hurting their ability to have the kind of mutually gratifying relationships that we want them to be able to have as adults. And that’s harmful to them and it’s harmful to the people that they partner with.

Yeah. I wonder how do you have a relationship without a strong sense of empathy or vulnerability? Um, so how does that play out in their relationships based on some of the interviews that you conducted?

Well, I think you really see that had kind of the heart of hookup called culture, um, which is pretty prevalent on college campuses and increase along high school. And you know, hookup itself is kind of a meaningless word. It can mean kissing. It can mean groping. It can mean intercourse. It can be in groups of here, no idea what somebody is saying when they say hookup. But hookup culture is the idea that um, physical contact, some kind of sexual contact is supposed to precede intimacy. Um, rather than be the product of emotional intimacy. And that culture prioritizes, you know, sort of disconnection and um, lack of communication and lack of connection. So as one guy said to me, you know, it’s weird and hookup because you feel like it’s two people having two very distinct experiences and you know, there’s not a lot of eye contact, there’s not a lot of um, communication. And he said, it’s like you’re acting vulnerable but you’re not supposed to be vulnerable, which is kind of odd and not really very fun.

Right? So now we’re going into high school. So, uh, in childhood boys start to learn, as you mentioned, um, sort of the gender performance, what it means to be a man. We hear things like boys don’t cry, uh, or man up, toughen up, suck it up. Uh, things that encourage us to push past feeling our emotions. Um, and so we move into high school, emotionally detached, and you start seeing hookup culture, uh, as you mentioned, which is a big part of this book. Um, one thing I found fascinating was, uh, sex, not so much for the pleasure or the emotional connection, but you mentioned more in boys and sex about a vehicle for social status. Can you talk more about that?

Yeah. I mean, so much of hookup culture is about not about the connection that you’re making with the person you’re with, but the invisible audience in the room, um, and real seat, you know, often see it this way too. This is not exclusive to boys, but it plays into the way boys are socialized and sort of entropy advantage in boys. Even though a lot of boys that I met, um, felt ambivalent about it or you’ll serve by it. There was that sense as boys is, as one boy said to me, you know, it’s, it’s competitive. It’s, um, an accomplishment. Um, it’s something, you know, you’re, you’re out to impress your guys. And as one boy said, you know, if you to do that, you’re going to be a little aggressive. You’re going to push because the girl is there as a vehicle for you to get off and to use to Brugge.

And when you kind of go into the locker room culture with boys that we’ve been talking about for the last few years, um, the language that they use around sex is kind of weaponized languages. You hammer, you bang, you pound, you now you hit that, you tap that you pipe, you know, whatever. But it sounds like they’d been to a construction site, you know, not like they’re engaging in an accurate intimacy. And I would find the boys, you know, as we were saying, there’s the wall, right? So there’s what they really feel a lot of times, which is not comfortable with that and what they think they’re supposed to feel, which is that everybody else is expecting that of them. And then then the reality of what happens when you try to push back against it. So one of the guys that I was talking to whose name was Cole, um, he and a friend, um, you know, said something when, when an older boy in high school boy, um, was saying something, you know, gross about some girl and they other boys made fun of them.

And so the next time somebody said something cool, said he stayed silent and the other boy kept saying something and he said as he watched his friend step up and as he stepped back, you know, he, he saw that this other board that guys weren’t listening to him, they didn’t really want to be friends with them anymore. That he was, you know, marginalize that he lost his social capital and Cole said, but I still had buckets of it and I wasn’t spending it. And you know, I don’t know what to do because I don’t want to have to choose between like dignity and these guys, but how do I make it so I don’t have to choose? And I really thought a lot about how that silence in the face of misogyny, sexism, homophobia, whatever it is, I’m in, that silence is really how boys learn to become men.

Yeah, that’s so true. And I find that challenging in myself as well. When I see that behavior. Um, there is this internal negotiation, especially when that person is your boss, uh, where there are these power dynamics. Where do I speak up against my boss? Do I challenge them? Will I lose my job if I speak up? Um,

personal safety issue. And for boys it can be a personal safety issue. They fear being targeted, they feel being, and everybody, you know, they’re teenagers. They want to belong. They want to be part of the group, you know, so, so working with boys, um, they’re, you know, there’s, there’s, I have a lot of resources on my website too, um, for people who are interested in this, but figuring out how to work with boys so that they can recognize that most of them really don’t want that kind of culture and what they can, how they can connect and push back against that. Or even think there’s, um, a sports culture, you know, is, is a place where that often takes place obviously. And sports can be great. You know, they, they can be fun. They build character, they can grow teamwork, all those kinds of things.

And they can be a smokescreen for the worst aspects of bro culture. Um, and so they can be a crucible of that, but they can also be a crucible of change. And there’s programs like, uh, and I think that this is, um, in Seattle coaching boys into men where they, um, mobilize and leverage the, the capital of coaches who are mentors and real role models in boys’ lives to do a very light intervention with young men. It’s like a weekly 10 minute intervention that has been shown in research to, um, reduce sexual violence, increased bystander intervention, and reduce that kind of weaponized language that boys use.

Yeah, that’s fantastic. I’ve been a part of a program here called wholehearted masculinity, uh, which I highly recommend for any men out there listening, um, as well as the consent Academy also here in Seattle. Um, but we really do need a new kind of role model that we didn’t have growing up. Um, and I feel like it’s never too late in adulthood to still sort of rewire the brain and unlearn some of those toxic behaviors.

Yeah. And I think it’s so important, you know, I’m so glad to be talking to you as a guy and you know, it’s fine talking to women too. I love talking to women, but, um, when then adult men can step up and, and model those things for boys or engage in the discussions with boys because one of the things that boys said to me was that they really wanted their fathers in particular, but I think any adult man that is, you know, um, a role model in their lines to talk to them about sex, about the emotional intimacy aspect of sex and about their own regrets. Um, and I know that that’s hard to do as a guy because it does, it goes against everything inside of you, right? You have your social and certainly your father probably didn’t do it with you. But I think for guys to know, you don’t have to be perfect, you know, you don’t have to know all the answers, you don’t have to know all the questions. You don’t have to have the perfect relationships yourselves, but just to start somewhere and engage in the conversation. And that’s really what I wanted boys and sex to do was to help not only parents but guys themselves to be able to, you know, get beyond that guy talk and, and maybe have and create a more meaningful dialogue with one another and inside their own heads.

Yeah, definitely. Yeah. I feel like being able to start from that place of, uh, elect this quote, uh, we’re all a work in progress. Um, this idea that we can constantly be growing, constantly changing and we’re not this fixed sort of static person. Um, but we can keep evolving at any time. Um, right. And

look how we’ve had this conversation where we’ve started with, you know, what goes on with and [inaudible] in infancy and move forward and, and you know, realize that as an adult man, you have the capacity to examine your life and interrogate your socialization and your choices and all of that and to make change and then to bring that change to the next generation.

That’s awesome. Yeah. I feel like being able to look at what we’ve learned in a more, in a more, um, explicit way. So like what did we learn about consent? What did we not learn about consent? What did we learn about bro culture, um, about sexual conquest as sort of a, a means to social status. Um, one of the things you mentioned earlier was this idea of pushing it, uh, or being aggressive, being overly assertive when trying to sort of reach these goals of conquest. Um, one of the things that I’ve read is the safety of asking permission from a woman is a sign of weakness. And not even just a woman, any partner, any sexual partner, you might have this like misguided idea that verbalized consent kills the mood. Uh, but there is someone in that you interviewed in boys and sex who thought that asking for consent was actually sexy. Uh, that hearing that yes was exciting or even thrilling. Uh, can you share a bit about his enthusiasm?

Yeah. That his feeling that, you know, when you, when a girl was really into it and she was saying, you know, yes, I want this. Yes, let’s do this. Like, what could be a bigger thrill? Um, you know, also it was really interesting because gay guys were a real model of negotiating consent and navigating the parameters of our sexual relationship and, um, you know, because they had to be right, because what was going to happen between them and what was going to do, who’s going to do homework, what and how. And you know, all of that cannot be assumed. Um, and so often in a heterosexual pairing, um, we make that assumption that we shouldn’t, um, about what’s going to happen. And so they had to learn how to talk about it. And you know, one guy said to me, you know, I don’t really understand this resistance of heterosexual men to talk about concerns of what’s going to happen because like if we’re talking about it, it means we’re going to have sex. Right? And that’s pretty great.

Right?

So what, what dance average Seattle guy talks about is the four magic words that gay guys use before in a counter, which are, what are you into? And I love that because it’s a really, it’s a classically open ended question. And so often when we talk about consent, we think of it as a prescribed series of questions. That one partner, usually the man is asking the other partner usually or the woman to solicit a yes or no. And this is a totally different way of thinking about it that said, um, Dan’s a gay guy who has sex with other gay guys. And, um, I worry that if you were to put a young heterosexual couple together and say, the guy said, what are you into that because of the way girls are socialized, the answer would be, I have no earthly idea. You know, because girls as I talked about and girls and sex get so cut off from their bodies and their desires. So that book shows the dynamic at play and the ways that you know that, that she’s kind of perfect storm socialization with men and women. Um, but also the possibility and the opportunity because what if we could raise our kids to ask that question and have that conversation?

Yeah, exactly. I thought those four, the four magic words are so powerful. What are you into? Cause it’s actually starting to give power back to your partner and allowing them to answer what they would like, what their preferences are, what their expectations are, um, what they find pleasurable, what they’re okay with.

It was very interesting because I recently, I was speaking about girls that are in an all girls school and her father raised his hand and said, um, I’m troubled about how we talk about consent because it always seems that it’s, that it’s framed as female response to male desire. They’re saying yes or no, the male desire, where is my daughter’s agency now? Where is her desire being expressed? And her question being asked, and that’s a lot. I’ve got the question for you do this is the question, what are you into?

That’s incredible. I love that. That apparent is challenging. Even just that paradigm where consent isn’t enough. Um, yeah, and I love how you broke that down further, which was really helpful. Like let’s get into more details about consent. Uh, you broke it down as consent is not just a yes or no, but consent must be affirmative. It must be knowing ongoing revokable freely given. Can you speak to, uh, some of these are why it’s why we need more detail or nuance with consent.

In the last chapter of boys and sex life, I really write very clearly. We’ll hold definition of concerns, um, as it is currently understood because I realized that CIM, any kind of adult people with children, um, don’t really know what it is. And so yes, it’s, it’s affirmative silences and consent. Um, it’s knowing you can’t consent when you’re asleep or involuntary restrained or incapacitated. It’s ongoing. And that’s the ongoing piece of very important because, um, one of the things that we know about young men, especially if they’ve been drinking, first of all, they tend to over perceive. Yes. So like any act of feminists on the part of a young woman and I am talking about heterosexuals here can be perceived as it’s on, right? They under perceived no and hesitation. Um, they also have a tendency to think more that than than young women would.

That, um, consenting to one act means consenting to everything. So, you know, kissing is consent to intercourse or going home with somebody means consent place, you know, that that space can mean consent. So, um, kind of recalibrating and helping young men really understand the gender dynamics that are at play at our heads that make us justify things that might not be consensual. Um, because you know, what happens then is that guys, it’s we really only think of sexual misconduct or sexual assault as something that monsters do, right? And only monsters assault and anybody will sell it as a monster. But the fact is that I talked to a lot of really good guys in this book. Really lovely boys, loved every single one of them. And a really good guy can do a really bad thing and we have to, and there’s a lot of reasons, you know, there’s some times that’s the analogy.

Sometimes that’s ignorance. Sometimes that’s just the socialization that makes you justify. Um, because we don’t want to believe that what we’re doing could possibly be misconduct cause we’re good guys. Therefore we can’t possibly be committing this conduct. You know, um, that kind of unraveling that not, and looking at the socialization, um, that boys undergo that can make them perhaps turn away from, um, their own behavior and not look, look at Brittany. I, it’s really important so they can have better interactions. Cause I think the upside of all of this was they wanted to, it wasn’t like they were all going around, you know, like saying I don’t care. You know, well they didn’t care that much in the hookup about female pleasure, but you know, do they, they, they care today certainly to the extent that they didn’t want to be assaulting people.

Right. At least not consciously or actively going out to hurt someone. Um, I think there’s very much a subconscious training that,

and so challenging that because we all, you know, the long game is that we want people, regardless of their body parts, you know, to be able to have mutually gratifying personally fulfilling relationships, whether those encounters are, you know, five minutes or whether they are inside of a 50 year marriage.

Right. Yeah. And that brings me to, uh, you started to state the differences between consent. Having consent and ethical sex and that you might have consent, but the sex falling after might not be ethical. And what did you mean by, what did you mean by that? What’s the importance of,

and it might not be good sex that’s consensual, that isn’t light. Um, or you know, you can, you can consent to something that you don’t really want, you know, to, it’s a much, it’s a more nuanced conversation. Ethical sets. So I [inaudible] is a looms, a health educator in the Bay area who wrote this fantastic book that I’m always recommending to everybody. Sex teens and everything in between. Um, she says sex should be, um, essential, ethical and good. And by ethical shame means you know, you, you taking into account not only the, um, people in the interaction, but who else might be involved. Like if you had an affair with your, um, your, with your best friend’s girlfriend, you know, that might be consensual but not so ethical. You know, there’s a lot of situations where something you can say yes to something, but that doesn’t mean, you know, it’s a really ugly, solid thing. And you can say yes to something and that doesn’t mean that it’s going to be good or feel good. So we have to, yes, consent. Yes, we have to talk about consent. Absolutely. And all of these dynamics. But that can’t be the only thing we talk about when we talk about sex. And I was going to say young people, but really with anybody. Um, we have to talk about these other aspects. And that includes talking about pleasure.

Um, when it comes to this idea of good guys versus monsters, uh, this idea of a few bad apples or as you mentioned, a quote versus, uh, a rotten orchard, the sort of systemic issue. Um, how do we start to sort of go beyond just good guys versus monsters? Um, the sort of extreme over-simplified characters.

Well, again, you know, I mean, what I want to do with boys and sex was, was have that complicated conversation to bring forth these voices of boys and the voices of, um, to, to, you know, to adults who, who raise boys as well as the boys themselves. Because it is a more complicated conversations in that. Um, so there’s a lot of, um, interest in that conversation. One place in the book that, uh, I really struggled with how to talk about how, what I could add to the conversation around sexual assault on college campuses for instance. And so I have a chapter in the book that looks at our, uh, at two people who have had a fairly typical interaction that he thinks is a bad hookup but is in fact assault. And there is, uh, it’s a, it’s a story that unfolds over four years and at the center of it is the idea of restorative justice, um, right. Where the idea is how do we repair the harm down here and how do we allow young men to take accountability for their actions, um, to make amends and how do we help them create that accountability to one another? So I wrestle a lot with that in that chapter.

Yeah. I’m so glad you brought up restorative justice. Cause that was something that I was able to be a part of with a different, a couple or a different situation where I was sort of called in as a mediator. And I was very grateful to see that process. And it was actually the only time in my lifetime where I’ve seen a sort of restored of justice process go from beginning to end, uh, with both voices involved. Um, yeah. Yeah,

it’s a, it’s a great tool and it’s not, you know, it’s not a magic bullet, but I don’t think that we can suspend or expel our way out of campus assault. And a lot of times people who’ve been harmed, um, and I’ve failed sexual situations don’t want that, but they, and they want to keep it a level of control too. And this allows the, the, the hope I think that the people have is that they can be heard, they can be understood by the person who harmed them and that that person won’t do it again. And this creates an alternative pathway to that, that, and, and the story of the boy in that chapter, it goes back and forth between his perspective and hers. Um, you know, he really starts out quite typical, you know, talks about learning about sex from, you know, van Wilder movies and porn and, and uncles who told them that I was successful a night out and successful unless he gets a girl’s phone number and was, you know, heavily into his frat culture and everything. And this allowed him to really take a look at what he had done, move through the phase of thinking, Oh my God, this makes me a monster too. Okay, what can I do to be accountable? How can I make amends to this person and moving forward? Maybe how can I be a better man and help other men do better men too.

Yeah. You mentioned a van Wilder and sort of those college frat comedy films you could call them. Um, so often those films are filled at so much misogyny and violence that it’s weird to even put them under the category of comedy. Uh, which is sort of something as boys we have to unlearn to see or be more critical of. Um, but I want to talk a bit about, uh, if parents aren’t doing the guidance, let’s say, of having those tough, uh, uncomfortable conversations, that the media would be the default educator. Uh, what did you mean by that?

Yeah, so the media and porn, mainstream media porn, and I actually want to talk about mainstream media first because one tends to get caught up in the porn conversation because, you know, I think we’ve done a much better job with girls on recognizing the harmful messages that they absorb from media consumption and whether it’s movies or TV or social media or YouTube or video games or you know, it goes on, whatever the thing is this week that they’re tick-tock talk, whatever. And we record, we’ve recognized, you know, that so often those messages are commodified [inaudible] transactional ideas about sex that she’ll nail into vital month of true female sexual availability that we do swim into their bodies. And we work with girls to be able to see that and resist it. But boys grow up in that same culture and more so, and nobody’s saying anything to them and they’re just sort of swimming in it.

So as one guy said to me, you know, I think music is a really plays a really big role in how, um, guys treat girls. You know, you’re driving around in the car with your friends and you hear, fuck that bitch and Twitter for five, six, 10 times in the space of a couple of hours. You know, it starts to affect your mindset. So there’s the whole piece of mainstream media that we, I think we tend to forget when we’re talking about porn, but that said, there has been a major change for anybody who can’t move. He went through puberty post 2007, um, particularly around porn. And I want to say that, you know, curiosity about sex, normal masturbation, yay. Really great way to get to know yourself. Um, and there’s all kinds of porn. There’s ethical porn, there’s queer porn, there’s feminist porn, but that is usually behind a paywall.

And what changed was that in 2007, PornHub went online and dropped the paywall. And after that you could see anything you wanted to. And you know, really a lot of things that nobody wants to right at your fingertips with your smartphone. And young men are looking at that from really, you know, sometimes when they’re very young, somebody will turn it around, you know, unwanted and show it to them. But they start to seek it out right around puberty and are learning to link, um, that cycle of desire, arousal and release with porn. So that, you know, one guy said to me that there was a boy in his crew team that said he wasn’t getting his point anymore. And they were, you know, they’re like, Whoa, how you do that? And he said, I used my imagination. And they’re like, Whoa, Whoa dude. That’s like, he’s like a legend.

I’m blown, mindblowing yet. So, but the issue was is that the porn that is, you know, that first line most easily accessible stuff tends to portray a really distorted idea of sex to people who have no actual experience in a world with other people. So there it’s, you know, if you’re an adult, you go do whatever you want to do. But for kids it’s showing them over and over and over and over and over that sex is something men do to women, not with them. That female pleasure is a performance for male satisfaction and also wildly inaccurate. Bodies are distorted. You know, there’s a whole lot of stuff even in vanilla slips that really wouldn’t feel that great to most people. And so if we’re not getting, we’re ignoring that and you know, just pretending it doesn’t exist or thinking like it’s like seventies porn, we’re doing a real disservice to boys because even though they say they know the difference between reality and fantasy, what research shows over and over is that they actually, uh, boys who watch porn regularly actually are more likely to believe that the images it depicts are accurate and they’re more likely to want to take those ideas and behaviors into the bedroom.

And they’re also less satisfied with their partnered encounters and with their own performance and with their partners bodies. And I always sort of think about one boy because it was such a poignant thing to say who said to me, you know, I think what corn has done for our generation is to just ruin that innocence of being able to explore sexuality without a preconceived notion of what it is. And that that whole organic process he said has just been fucked by porn.

Yeah. And I think you mentioned in the book about a young boys who are immersing themselves in porn and all kinds of porn, um, that haven’t even had their first kiss yet. Uh, maybe haven’t even gone on a date or held someone’s hand. Yeah,

exactly. So, exactly. So, and it gives, that’s what I’m saying, you know, if you’re an adult, you’ve, you know, you’ve, you, you understand the world a little better, do whatever you want to do. But, um, we don’t know the impact, the full impact. I mean, we can see that certain behaviors have changed. Certain be, you know, there’s more anal sex, there’s more choking, there’s more of, um, certain behaviors. But we don’t know the full impact of this great experiment that we’ve done on young people and particularly on young men. Um, we can see generational differences in how people use porn and a difference between fathers and sons, for instance, for mothers and daughters. Um, but we don’t really know yet what kind of impact that’s going to have. But we do know that even when we think it doesn’t, because that’s what everybody thinks, that the media we consume affects our thoughts, our feelings, our beliefs and our behaviors.

So, you know, that can give us some insight. And that whole chapter, I hope because it was one of the things that boys most wanted to talk to me about in fact, because it’s so new, this idea of like 24, seven access to, you know, massive amounts of commerce. Um, that whole chapter I wanted to, again, you know, for parent aged people to help them understand what the culture of their boys are in and that they need to talk about it even if they’d rather put themselves in the eye with a fork. Um, but also for boys themselves to sort of, you know, understand what’s going on and what research is real and what research is not real and maybe even think about differentiating between that which is highly arousing and that which is actually pleasurable and wanted

right in the end. That’s a really great difference between sort of the, the sort of subconscious cultural teachings of the media versus an intentional conversation with your child, um, as they’re growing up, having those difficult conversations. Um, when it comes to parenting or raising young boys or for people who are thinking about raising a boy, um, what would you say to them in terms of, um, sort of how to have this conversation?

First, I’d say it’s not one conversation. You know, it’s a series of small conversations over time about bodily autonomy, about sex, about consent, about pleasure, about media, about, you know, accountability. And in the chapter of the book, I did something that I’ve never actually really done before. Um, because I’m a writer and what you learn as a writer is that you’re supposed to show, not tell. And so I’ve always operated on that Maxim and taken readers into, you know, a school or classroom or, or profiled somebody or done something that would show, you know, the way forward through this story. Um, and I kept trying to do that, but it wasn’t working. And I realized that I had been writing about young people and sex for about nine years now and at this point that has some things to say. And so the whole last chapter, I can’t give you a script, but I can’t give you a bit of a template of the kinds of conversations that you need to start engaging with from the get go.

You know, as we started this conversation with helping boys name their feelings and expanding their emotional range beyond happiness and anchor, that in itself is a really important thing to do. And that’s not about sex per se, but yes, it is. Right. And I would really hope that in having discussions like the one we’re having today, um, in reading books like boys and sex and having parents, I’m starting to, to have these conversations that we create an environment, um, that allows men to be there, to have their full selves and to really, you know, be them on that. We know they can do.

Peggy will be coming to town hall on January 23rd at 7:30 PM to talk about her new book, boys and sex, young men on hookups, love porn, consent and navigating the new masculinity. This is a completely sold out event, but you can always try to get in our stand by line night of. We’re also planning to livestream the event unearned town hall, Seattle YouTube channel so you can watch it live or in perpetuity. Just go to YouTube, search town hall Seattle and subscribe for more information about some of the organizations that were referenced in this interview. Click the links in the episode description below. Thank you for listening to episode 50 of in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle baseband, EBU and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. You can listen to our town hall produced events on our arts and culture, civics and science series, podcasts, and to support town hall. See our calendar of events or to read our blog. Check out our website at town hall, seattle.org next week, our chief correspondent Steve Cher. We’ll talk with Samuel Wasser about preserving elephants in the age of extinction. Till then, thanks for joining us right here in the moment.