Episode Transcript

Please note: This transcript was generated automatically, please excuse typos, errors, or confusing language. If you’d like to join our volunteer transcription team and help us make our transcript more accurate, please email communications@townhallseattle.org.

Hello and welcome to in the moment. I’m your host, Jenny Palmer. We’re nearing the end of our month long September homecoming festival here at town hall Seattle. This past week, art, music and panel discussions filled our building. We hosted a live comedy podcast. Craft your hours in the forum post event and a vital conversation took place in our great hall about our climate crisis between Naomi Klein and Teresa mosquito and even though these events have passed, you can watch the live streams or listen to these events on our media library page at town hall, seattle.org we’ve got one more week left of the festival and a few more music and educational programs to add to your agenda tonight. We’re hosting the city council debates for districts three and seven, so swing by and educate yourself about how you’re going to fill out that ballot. Our global rhythms music series is having their first concert of the season, this Friday night, which we’ll be bringing the history and soul of Garifuna culture to life, Garifuna collective and how Gucci Garin AGU will be playing their traditional rhythms in the great hall. At 7:30 PM if you’ve got kids swing by Saturday morning at 11:00 AM for a Saturday family concert with Ricardo beauty and how good shag Aaron AGU. That same day, Alexandra Horowitz, our subject for this episode of in the moment we’ll be talking with science writer James C who about our dogs ourselves. We’ve got a whole slew of great events to come, so do yourself a favor. Check out our calendar, get yourself a seat and join our townhome community,

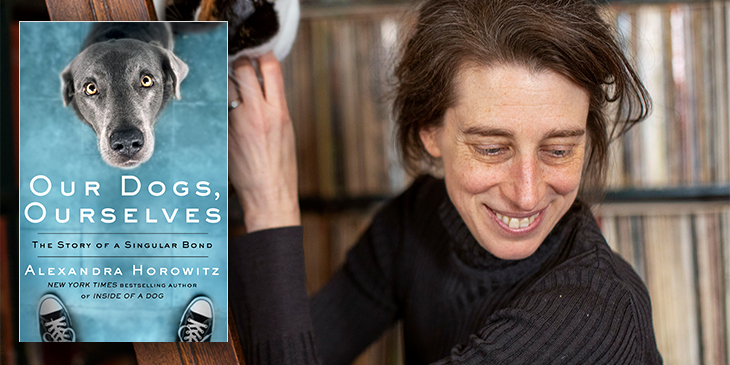

Who we are with dogs is who we are as people rights. Alexandra Horowitz, the head of the dog cognition lab at Barnard college and our town hall guests September 28th in her previous books about dog behavior and intelligence, the writer and researcher focused on the dog’s perception of their world. In this conversation with chief correspondent, Steve share, Alexandra turns to the relationship between humans and dogs. It is a relationship that has changed both species and depending on how we decide to proceed could change our relationship even more. Our dogs ourselves explores the laws and cultural choices that currently dictate the dog human relationship. Cognition, scientists like Cora widths are uncovering facts about the bond that could’ve been end parts of that relationship. As Horowitz told Steve share in the last few years, the amount of research into the dog’s understanding of the world has gone from a trickle to a flood.

Well, there was a trickle. So, you know, address both ends of that. Natural formation. There was a trickle first because the dogs I think weren’t considered cognitively interesting too. The comparative psychologists and animal behavior researchers who studied all manner of species, especially comparative psychologists who were really keen on animals who were more like humans because we were interested in seeing, you know, how much they matched us or reflected us or how much better we were at skin tasks than nonhuman animals, I would say. And so dogs were considered maybe not likely to show interesting cognitive abilities. And also they’re, they’re so familiar, they’re so well known that I think people thought, well, why do you need to study this? You know, familiar dog. But then when some of the early research came out and showed that in particular dogs have these excellent social cognition skills where in, they can use others to solve problems.

You know, they can understand a little bit of other minds, something that we value in human cognition. Then people got very excited about dogs as a potential study subject. And of course, they’re much easier to study than some of the animals who had been studied. So if you’re studying chimpanzees, you know, you have to keep chimpanzees, which is logistically quite difficult. And you know, if you know a lot of chimpy chimpanzees, you might say morally hard to justify keeping them in small cages or small enclosures, or you have to find them in the wild, which is also really difficult, you know, because they’re just living their life. So dogs were easy to, to study. They were looking like interesting subjects all of a sudden. And that accounts for the river of research that we now find ourselves waiting in.

What do you think about the research that you’re seeing? What, what most inspires you perhaps, or what most does it inspire you about what you’re finding?

Okay. Well, you know, the research I do is I’m a little eccentric. I think it’s not kind of the standard line dog cognition research where you’re asking the same cognitive questions of dogs that you’re asking of humans or other non-humans, you know, how do they solve these tasks? Can they imitate things like that. But there are other people doing, you know, slightly odd research you asking questions about you know, whether our anthropomorphism is that we make of dogs that attributions to their abilities or emotions or our skillset are, are correct. I love that type of work. I like the work that’s been done about olfaction and I try to do olfactory research where we’re trying, you know, we’re really getting a handle on how little we know of what their abilities are and what their experiences via smell, which is their primary sensory modality. So those things to me are the most exciting types of research in the field.

You do two things that are very interesting to me. One is the to well you talk about uhm, well right. And [inaudible] talks about wound wealth like this. How does the animal, how does the creature itself see their place in the world, which is a very different way of viewing a very dumb way of viewing science, right, than it has in the past, which is used it as utility. And so you’ve done that just by walking in, observing with your dog and what that w with your dogs and other dogs, what they see and what they experience and, and trying to, is it fair to say, trying to get inside their minds, is that fair to say when you’re on a walk with your dogs?

Sure. Yeah. I mean, my research or my just casual observations are, are really pointed in that direction as you say, to the, what it’s like to be that animal.

And what about the work you do with when people come to your when they come to your lab, you are looking at them as paired with their humans. Correct. Not the dog in and of itself sometimes, but their interactions with their, with their humans, isn’t that right?

It’s both. It’s both the dog human relationship, depending on the study. You know, we’ve studied document play for instance. But it’s also what the dog how the dog performs on some task. I, I give them because I’m interested in you know, can they smell different size quantities of different quantities of food for instance. And the, and the owner comes along when the dogs come to the lab. But I asked the owner not to really participate in any way. They’re there just for a sort of moral support. But I don’t want them cuing the dog. So the owner is significant in those studies because the dog really does want to get a cue of how to behave from the owners. But I, but I’m trying to leave the owner out of it as much as possible.

The dog wants the cue from the owner and the owner wants to give a cue to the dog. So they’ll perform in the in the way that they feel better, best about them, right?

Yeah. Just like in psychological studies that we participate in ourselves, people often want to succeed at the study, right? So they form some notion about what the study is about and then try to succeed at it. Even though it, they’re probably wrong about what the study is about. And it’s not obvious what counts as success really. You know, psychologists are just studying how we behave. So the dog people come in and want their dogs to, you know, be great, [inaudible] perform well and it’s really never about that. And as much as I can keep the owner’s in the dark, frankly, when they’re there about what the study is, the better because that way they don’t, there’s, there’s no way for them to helpfully cue their dog to perform in a certain way.

What about the dog? Does the dog also have that desire, want to perform to be great?

I would say that all appearances are no, they do not because they don’t seem to want to perform to a level. They’re just interested or they aren’t interested. They notice a difference between stimuli or they don’t notice a difference. Right. Or they’re motivated to participate and find the next thing or they’re really not motivated. So they don’t seem to have performance anxiety.

Yeah. Does, what does that, if anything, what does that tell you about the dog mind? The theory of mind of a dog?

I mean, I think that tells me that they haven’t taken on all our, of our bad anxieties and habits for them.

Yeah. Good for them. Do you have a, is there a recent experiment you’ve done or your lab has done that you were particularly just found fun and joyful?

You know, this, while it might seem odd to you or, or your listeners, but the one that I did recently, it was actually about two years ago that I loved, was this thing called the, what I call the old factory mirror test. And I was modeling this after a really interesting tests that Gordon Gallup will primatologist developed many years ago. Wherein he asked, you know, do chimpanzees have an understanding of themselves, self-awareness. And he represented that if a Chimp could look in the mirror and see that, you know, there’s something that there was something on their forehead, for instance, a little red Mark and move to touch the red Mark on themselves, you know, through, through the mediation of the mirror just as we would if we looked in the mirror that it showed that they might have this kind of self awareness. This is me with the Mark in my head, just as we do when we look in a mirror, you know, by age two or something, you look and you say, you know, that’s not another kid.

That’s me. And I can use the mirror to, you know, change my, to try to look differently. And self-awareness is one of these things we’re really interested in another, whether other animals have, and this is a flawed test, but really the only test we have to try to study it. And dogs don’t pass this test. Typically they, you know, if they, they seem to use mirrors maybe to find out about the world. So they, so they see them and can see things in them and maybe understand that things are behind them in that they see approaching them in the mirror, but they don’t seem to look in the mirror and see something different about themselves and then move to change. And I reasoned, well that’s because they don’t really care. You know, what they look like so much. I’m a, they’re not like a grooming species like primates, but also, you know, they’re smelters primarily.

So what if they kind of smelled themselves and noticed that they had a different smell? Would they be more interested in that than what they typically smell like? And so I created a little study where the, I presented them with their own scent and then their own scent, which was modified by another smell. And I also presented other little odors to them, like the son of another dog that they didn’t know or the son of a dog they lived with at home. And I was looking at how long they investigated all the samples. And what I found was that they were way more interested in their own scent when it was modified with another scent. In other words, just like looking in the mirror, somewhat like looking in the mirror and seeing a Mark on your forehead noticing that’s you. And it’s more interesting than just you because there’s something different there.

And there were more interested in that than their own image or then just the scent by itself. Right. It wasn’t just that, that’s a really exciting sense that’s been added to my smell. Mmm. I want to smell that it was that it’s me, but different. And that’s weird, you know, and I want to investigate that longer. So to me this was a very cool experiment because it’s all about trying to understand that infect like what is the olfactory experience of the dog, how do they, how do we get it? How you might think with olfaction. And it was an attempt, you know, albeit I think the flawed one and at first pass effort, but an attempt to start to get at that.

It’s also, isn’t it the the reason why the trickle has turned into a river because so many scientists like yourself are envisioning investigating the world in new ways, in ways that show us the animals or show the animal’s thinking rather than our thinking about the way the animals think culturally. What do you think is prompting that?

The availability of these dogs allows us to be a little inventive and come up with new things. But the field itself really is always evolving new methods to try to get at the minds of animals. So, and humans for that matter, you know, and so like brain imaging is a field that’s really exploded and one reason we’re excited about it is just another way in to the mind, you know, the another way into find out things about ourselves or others that are, it’s hard to find out otherwise. So, I mean, I think we have a natural curiosity and the field re reflects the curiosity that we as a society feel about ourselves and about our relationship with the in our culture.

Yeah. It’s also, isn’t it interesting that it’s a, it’s the dogs that we do that with because we’re so familiar with them and yet we’ve, and we ascribed so much to them and yet we seem to also want to actually know if what we’re ascribing is real, it seems important to us that it is this real

Want confirmation. Right. You know, is it, people ask me a lot if, if their dogs loved them, you know, if that’s fair to say. And I, and I say, you know, I haven’t spoken to your dog, but but they, but they want, they want some confirmation, scientific confirmation. And yet, you know, if I told them no, I think a lot of people, and you’re talking to Scott, which is not what I believe, but if I had said that, I think a lot of people would still go away and say, you know, but, but my dog, I know, I just know my dog does. So we use science and the results of science as, as part of our fact finding. But I think people also rely on their own intuition as well.

You somewhat tongue in cheek in your biography say that you know, you are, you are owned. She’s owned by canines, Finnegan and Upton and been tolerated by the feline Edsel. What’s unpack that, that that joke you’re making that, that you are owned by those dogs?

Yeah. It’s always inadvisable to unpack your own jokes, but I’ll do it for you Steven. The you know, while I’m playing with the fact that it’s odd that we talk about owning our animals and we do legally own dogs because, so the law, they’re considered personal property. They are objects that persons like us and own and do with more or less as we choose. But I feel like that’s in that right. And it doesn’t match how we feel about dogs, the familial feelings we have about dogs, they’re members of our families. So it’s weird to say and we own them, right? I was responsible for my son when he was little, but I didn’t own him. He was his own person. But I really, he needed me to get around and to grow up. I didn’t own him. So I feel like if we’re going to talk about ownership, I’d rather talk about it as a two way street that we’re mutually owned by each other.

You write about the evolution of, of a dog well, of animal rights laws or animal laws and then the, we come to the time of animal rights and the idea of what rights animals have and what rights dogs have. When you say that, you know, as property, they have the rights of chairs, the same, same rights as chairs have in many ways. What what, what do you think would be at, would the world look like if it were different and how, what would it be to make it different?

A lot of thinkers, legal thinkers are puzzling over that very issue. And one who I, I think has intriguing ideas named David favor suggests that for instance, just as we’re responsible for children but they are their own persons. Maybe dogs could be a slightly different status. Maybe something like living property instead of just property where we’d actually have to take into account their wellbeing in a serious way more than the absence of cruelty as, as mandated by animal cruelty laws requires of us. If we did that, I think, you know, there might be some circumscription on owning dogs. If you weren’t a good owner of this living property, then maybe you wouldn’t get to own them. You know, think about how our society is decided over the last 40 years. Mostly because of Jane Goodall and the people who followed her and studying chimpanzees that we shouldn’t keep, except in extreme situations.

We should not keep chimpanzees for medical experimentation. You can’t just keep chimpanzees for behavioral research anymore. Captive. It’s inappropriate. We’ve decided as a culture to these kind of magnificent animals who are us. And so we’ve had to limit the types of things we can do with chimps. And I think that’s okay. You know, but it is a change and there might be a time when we’d say, well we have, we can still live with dogs. We made dogs. We kind of have to, we owe something to them because they are dependent on us. But maybe we can change for their benefits as a species and individually the things we can do with dogs, the ways we can own dogs.

One of your examples is the way breeders work, right? What are, what, what would breeders do differently if, if we had a little more attention to that aspect of the dog?

Yeah, there are a lot of interesting aspects of breeding ducks. Obviously, you know, you have to have, you have to make more dogs. We want to continue to have a dog population and breeders might be acquired that forever. But pure breeding is right now for matching of breed standard, which is which is largely about appearance and a little bit about temperament. And it’s led to some really serious health problems with lots of breeds because inbreeding as we know biologically is not a sound practice. So what if instead breed standards required that the dog be particularly healthy? You know, what if we were bred for health instead of for looks, that would be an improvement. And the very fact that we can as property sell dogs, I think if that were altered in some way or if, let’s say the dog got to have the benefit, some of the monetary benefit of work that they do for us, then our relationship with the species would change. But we’d still be living with the dogs. You know, they don’t have to, they don’t have to be full persons in order for us to give them a little bit more than we give them now.

Well what do you mean by that? Like what

[Inaudible]

I think people are concerned that if you treat animals that it’s anything but property that then suddenly, you know, you’re pretending that they well first of all that they would have responsibilities that they can’t live up to and then that you there’s kind of taking over, you know, that they take over your life. And I think that there’s a way that we could live with dogs and do more things to their wellbeing for their benefits rather than for our interests. And still have a dog human relationship. I think it’s, you know, a lot of the sciences pointed in this direction and a lot of animal welfare science, which is really blossomed in the last couple of decades, is about saying like, all right, we live around these other animals. You know, how can we treat them best if we’re going to look at the food industry and how that’s changed and our interests in finding food from more humanely raised food, right?

It’s that kind of thing. Can we more humanely deal with dogs given our knowledge of what they need in their life? They need social companionship for instance, like it’s, it’s actually cool to leave them alone most of the days as we often do. If we have a job that keeps us out of the house for 12 hours. What if you just couldn’t do that? You had to figure out something else to do with them during that time. Because we know that it’s a real stressor. This type of thing I think is, is the type of thing I have, we should have a conversation about as a society.

Well, one of the other things is one that you mentioned in your book is a spaying and neutering and that we have deliberately desexed dogs because it’s messy and it causes problems for us. What, well, we’ll give your thoughts on mandatory spaying and neutering that occurs at a shelters. For example,

The policy to spay neuter dogs has come about because we have a huge overpopulation of dots. That’s why mandatory spay-neuter grew in the, from the seventies to today to be a much bigger deal. And it’s entirely understandable that that happened. You know, people were having to euthanize millions of animals, dogs and cats every year. And it’s hard. Horrible. It’s horrible. Now we still have the policy, but we, I think it’s worth looking at it again whether that’s going to bring us to the place with, with domestic animals where we want to be. It doesn’t eliminate mandatory spending or it doesn’t eliminate the problem of two Benny overpopulations or too many dogs. I’m on a dogs. We still use an EIS, million some dogs and many more cats every year in this country. So, and we see other countries that don’t have spay neuter laws, in fact, where it’s illegal, where they don’t have a stray dog problem.

And so you have to say, well, this is the solution we took to try to solve this problem and understandable, but are there other choices? What would it be like to do other things, right? For instance, to discourage or make people aware of, of like the responsibilities of living with a dog who is intent to could impregnate another dog or become pregnant. What, what would you need to be able to take on if you’re going to be a breeder of dogs and create new puppies? You know, I think that we’ve put off onto this one policy. You know, we sort of treated as the solution to this big problem that we created of millions of dogs every year being euthanized because they don’t have homes.

Sweet

Got one solution. It’s, it’s just not a simple solution. It’s not solving the problem. And it also, you know, kinds of lets us off the hook when we shouldn’t be let off the hook. We need to be more responsible dog owners and all the other ways, you know, [inaudible] spay neuter is is, is asking the dog to bear the problem. That’s our problem. You dog the path of surgery because we humans have created too many other dogs and we don’t want more.

And yet we have more and more and more and more. Because there seems so many people want to have dogs. Sweden and Norway are two countries. You mentioned have tried some other approaches. What were their approaches? And do you have enough science to say, Oh, cause it, there’s some causality here. This actually is getting us towards a different solution that’s successful.

They’ve just taken a different approach the whole time. You know Switzerland has an animal protection act, which, which, which requires legally that you honor the dignity of an animal and that means no unnecessary surgeries and Spaniard or would be considered unnecessary because it’s harmful. It’s harmful, it’s a harm to the animal. The surgery is painful and unless you need the reproductive organs removed for some other reason, but cancer for instance it affects the whole body effects an animal’s growth. Deleteriously and their solution has been to put, prioritize the animal in that relationship and they have to spend a little more time making sure, a little more care, making sure that, you know, their dog and heat does not get out. Or if they’re gonna have puppies, they have to have places for those puppies. But it doesn’t appear to have gotten them at a worst plate is not gotten them the middle worse place than the U S or the U S is at a much worse place.

So that’s just, I’m not saying we should all be like Norway. I don’t know. I feel that that’s it. It should reflect though that what we feel is the only solution to this problem is not the only solution to this problem. So let’s find one that works for both humans and dogs because this one is not a dog friendly solution. This is in the book, this argument, this was also in the New York times recently. Did you look at the comments? Did you see what kind of reactions you got? I did not look at the comments. Because I wasn’t interested in, I wasn’t interested in engaging with two and a half

[Inaudible]

Responders. I mean, I feel like I’m proposing that we look closely at something, but I’m not mandating anything and I’m not requiring anything. I’m suggesting something. I’m saying, here’s some facts and that I’ve put together. And here’s some other ways to think about this beside the way that we’ve been handed, and if people are gonna yell at me about that, then I don’t need to be yelled at about that. You know, we’re on the same side. We’re both in favor of dogs. We’re both pro dog, so I feel like we should focus on that as opposed to arguing about the policy. So I’m glad that it was widely read as it appears to have been because that’s the idea is to say, Hey, this is something that we’re not supposed to talk about. So let’s just talk about it. I don’t believe that there’s anything which we shouldn’t be talking about. I mean, heaven forbid that that we have something we can’t be talking about that. That’s not what our society is about.

Alexandra Horowitz talking within the moment, chief correspondent Steve share for an extended interview between the two. Listen to Steve’s podcast at length, wherever you find your podcasts. Alexander Horowitz comes to town hall to talk about her new book. Our dog’s ourselves. The story of a singular bond on September 28th at 7:30 PM now go take that best friend of yours out on a long walk.

[Inaudible]

Thank you for listening to in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle based band, EBU, and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. Don’t forget to subscribe to our arts and culture, civics and science series podcasts. If you haven’t already, you can listen to the majority of Townhall produced events in their full form. On our next episode of correspondence, Sally James will talk to Paul tough about who needs college till then. Thanks for joining us right here in the moment.

[Inaudible].