Episode Transcript

Please note: This transcript was generated automatically, please excuse typos, errors, or confusing language. If you’d like to join our volunteer transcription team and help us make our transcript more accurate, please email communications@townhallseattle.org.

Hello and welcome to in the moment. I’m your host, Jenny Palmer. Well that’s it folks. Our homecoming festival is officially over and the stats have come rolling in. During our festival we had 52 main stage programs with more than 100 presenters. There were over 12,700 tickets sold across 4,500 households and 1077 of those tickets were claimed by a new 22 and under audience, which if you didn’t know Townhall is offering free tickets for youth. That’s right. Anyone that’s 22 and under can attend any of our town hall produced events for free and with a month long extravaganza of spectacular events in the bag. We can now turn to our regularly scheduled programming. We might be done with our festival, but we still have a packed calendar in October. Our rental partners are filling these autumn days with earshot, jazz, and sandbox radio performances and the moth will be packing our great hall with new stories for the grand slam champion. On October 25th ambassador Susan Rice will be coming to speak with former us secretary of the interior. Sally jewel. On October 14th and we have more than a few events to satiate that curious mind of yours. Basically we have another full month ahead and you can check it all out on our website at town hall, seattle.org but for now, let’s bring it back to this moment.

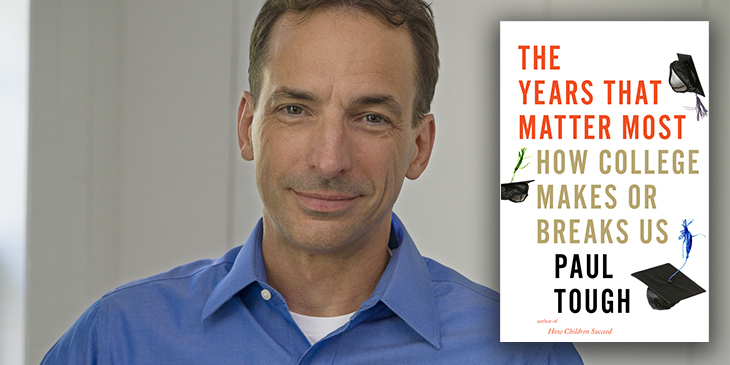

What does freshman calculus have to do with college admittance? Research has proven that higher education is an equitable and Paul tough a writer and journalist has written about that research and the landscape of higher education and his new book, the years the matter most how college makes or breaks us. Our correspondent for this episode, Sally James is a science writer based in Seattle who sat down to talk with Paul about the time he spent on college campuses with students and teachers and what he learned about higher education.

I I really enjoyed the book and I I read it with a couple of different perspectives. Both a parent who has sent three children to college and a former college student who was low income and going to a kind of pretend Ivy. So I found a lot of things in here that I think a lot of parents are going to be wondering about. I feel like we have to unpack a little bit. One of my favorite sections, which is on page 138 I’m going to set up something you said lacrosse bros really do run the world. It really is who you know and not what, you know, by the time you reached the last page of pedigree, you either want to go firebomb a bank or enroll your kid in squash lessons or both. Can you just talk a little bit about the D moralizing numbers on how inequitable higher education is?

Yeah, they’re really striking. So that I was writing in that particular chapter about this, this research by this sociologist named Lauren Rivera. That is not even about college. It’s about what happens after college and the way that all of the inequities in college admissions replicate themselves. And in some ways there are, are expanded on when college graduates or college seniors are applying to jobs at investment banks and law firms and consulting companies. But I feel like it is a,

It’s just an amped up version of what’s happening throughout the college process. And there has been over the last few decades this increasing stratification of higher education so that the most prestigious, most well-resourced, most selective institutions are now admitting students with a smaller and smaller range of test scores and are admitting more and more well off students and fewer and fewer low income students. And that is often not the way we think about it. I feel like there is this, this idea in the public sphere that in fact those most selective institutions are a real bastions of equity and diversity. And they certainly often talk that way, but when you look at the numbers and a study came out a couple of years ago that maybe for the first time really a lot easier to look at those numbers. It’s clear that there are very few low income students at those most selective institutions and the institutions that are at a, at educating a lot of low income students are the ones that we have been defunding and pulling resources back from over the past couple of decades.

And I, and that state schools for the most part, wouldn’t you?

Yeah. Pub public universities in general. So everything from community colleges to flagship institutions we’ve been cutting their funding for for decades, but especially since 2000, 2001. And even more, especially since the recession 10 years ago you know, we just slashed our funding in the recession and then never never restored it. And so all of the, like all these stories about rising tuitions and rising debt, at least on the public side, that all just has one, one main cause, which is that, that those institutions used to be something that we funded publicly and we have just switched the funding source from the public, the individual students and higher education doesn’t function well that way. And it certainly doesn’t function equitably that way.

I think we can segue because another one of my favorite parts of this is the entire chapter on freshman calculus. And just for the people listening, a very idealistic calculus professor at the university of Texas used some of his own history as someone who had what I’d call imposter syndrome during part of his education. And his success made him interested in rescuing other people from that. And I think students who have come from what you call less than gold plated high schools fall into a kind of trap where they aren’t in the same place as the other students on that first day of college calculus because the majority of other students probably took it already in high school. And I was gonna say, if you wouldn’t mind just saying a little bit about why freshman calculus represents an enormous obstacle to STEM careers.

Sure, sure. I’d be happy to. Yeah. So I’m so happy to hear that you like that chapter. My favorite chapter in the book as well. And I find that that calculus professor already tries them to be an amazing character and getting to hang out with him for a few months was a great opportunity. So so I’m always happy to talk about it. So one of the many sort of unusual facts that inform that chapter are the fact that calculus is role in the culture and in higher education has changed drastically. So when, when this professor 40 years ago was in college, only about 7,000 students from the whole country took AP calculus and now it’s, it’s hundreds of thousands each year. Something like one in five high school seniors takes AP calculus and, and the best math educators actually say like, we shouldn’t be teaching calculus in high school at all.

That if you really want to be a great mathematician, you need more grounding in high school in geometry and algebra and, and the sort of building blocks of calculus before you take it on. But it seems to be the case that that calculus has taken on this role in the culture and in college admissions of sort of this generic signifier of eliteness the same way that that taking Latin was a few general a couple of generations ago. And you know, like high prestigious colleges don’t really care if, you know Latin and they don’t really care if, you know, calculus, they just see AP calculus on your transcript and they’re like, okay, it’s that kind of kid. Right? they’re, one of the statistics that I still can’t quite believe though it’s totally true is that 93% of Harvard’s freshman has taken AP calculus or, or something even higher.

And that’s not just 93% of the math students, that’s 93% of the French majors and the music majors and the basketball players and everybody else. It just, it’s very difficult or very unusual at least to get into Harvard without having taken AP calculus. And that then has the additional problem that AP calculus is not offered in more than 50% of high schools in the country. And it’s not surprising to note that it’s not evenly distributed. So, so low resource, low income high schools are less likely to offer AP calculus or calculus of any kind. And schools that educate a lot of rich kids are much more likely to have AP calculus. So it’s become this gatekeeper that makes it very difficult to get into a prestigious universities without having, and it’s, you know, for more than 50% of high school students, they can’t take it no matter what they do. So it’s one more one more gatekeeper that makes it harder for low income students to succeed.

Well, and I think, I think just to help podcast listeners, I also think that, so let’s say you’re lucky enough you’ve been admitted to college and now you have to take calculus and get a good grade in order to be a biologist, a physicist and astronomer, a geologist, a doctor the student you introduce us to, Yvonne has so many things going for her and yet you give us a wonderful emotional play by play of her believing that she isn’t good enough. Even during the, as the, the weeks go by and week by week, midterm by midterm, she remains very on edge about whether she belongs. And I think what’s interesting is education has this image as something objective, mathematical, you know, GRA like gravity. If you have the education then you are, society is saying you are smart enough and yet she can’t get that message without an awful lot of kind of hands on encouragement from, from people. If we can’t reproduce Yuri, if there can’t be a URI at every, you know, big kind of flagship university, what other ways could we make calculous less of an obstacle?

It’s a great question. And so one of the things that I find really, really striking about that chapter is that, yeah, so like she’s learning, Ivana is learning math, which we think of as the, as, as you said, as this very sort of empirical, rational thing. You either like do the math right or you don’t, but so much of what is going on with her and I think she would agree with this and or either the professor would agree with this, with psychological. And she was in this, this sort of moment of great turmoil about her ability and about her ability to belong at UT and in Austin and you know, in this very elite worlds you want it to be a math major. And so she was constantly questioning whether she could do it or not. And so she was getting all of these messages.

And one of the things that is really striking to me is that, is that I think, I feel like early the messages she was getting from early men weren’t necessarily the most helpful for her because she was hearing from him that she was going to be fine. Everything was going to come together, just give it a few more weeks and suddenly everything was magically going to happen. She was hearing from her sister who was another, you know, high performing student, a UT student, but also from a, obviously from the same, you know, very low income background. She was hearing from her sister that actually she wasn’t going to succeed in calculus, that low-income Latinas from the West side of San Antonio just couldn’t pull this sort of thing off, which didn’t seem very reassuring but somehow felt comforting to her. And then it wasn’t until she, she had this one conversation with the, with her TA, this woman named Erica winter, that she found I kind of synthesis of those two arguments that really made sense to her.

This idea that you really are behind, like you really have had disadvantages and they’re not just imaginary, they have created these, these obstacles that are going to be very difficult to surmount, but those don’t define you. Those are not actually part of your, your essential character and who you really are as a mathematician and you’re going to be a great one. And if you want to close the gap between yourself and the students who have more preparation, you can, you’re just going to have to work really hard and really strategically. But you can do it. And, and, and I, and we can help you do that. And that I think was, that was the message that really worked for her. And I think it’s a complicated message to get right. But I think there are lots of lots of teachers who are working on how to convey that and how to convey that not only through words, but through the kind of math problems you assign and the way that you help students complete.

Well, my question has to do, again, I’m very, I’m very taken with how a parent can be both giving my child the appropriate skepticism. So for example, about standardized tests, how do you communicate the skepticism at the same time that you want to encourage and challenge? And I’m curious, when you think of, you know, three years from now, your son, three, four years, your son may begin setting down this sort of record that we’re all saying, you know, shouldn’t matter, but it does. And if he reads your book, what, what do you think he will, how will he put into action? The combination of skepticism and, and wanting to believe?

I mean, what I really hope that, that he and other young people take away from the book is amend might be a little bit counterintuitive, but it’s to, it’s to think about college admissions beyond their own specific case, right? Which is not how it, like we, we, we put so much pressure on our kids and they put so much pressure on themselves and the system puts so much pressure on them to just like get it right for themselves. And I want them to think not just about themselves, but about everyone in our community and in our culture who, especially those who had a few or fewer advantages than they do. And I feel like this is this generation that does think so systematically about inequities in this way that, you know, I don’t think previous generations did, whether it’s gun violence or racial discrimination or climate change.

I think they are, you know, really thoughtful about what, how advantage works and how disadvantage works and, and what kind of changes they need to make in order to make systems fair. But I don’t think that we encourage them to think that way about college and he, and so, you know, 15 or 16 or 17, we, we suddenly compel them to dive into this system that is inequitable and and, and perpetuates inequities. And instead of asking them to sort of critique it and, and, you know, have, have a, a skeptical view toward it, we just tell them like, this is the most important thing for you to win in this system. And so, so that’s, that’s my hope is that is that young people can sort of use this book to take a broader vision of, of what’s going on in that system.

And, and my hope is that not only will that make them, you know, more active and more concerned with reform, but it will also, I think change the pressure that they feel about their own, their own outcomes. It’s like once you start caring about climate change, you no longer want to have the fastest car, right? Because you know that the fastest car is actually also destroying the planet. And so my hope is that the same thing can be true. Once you start caring about the, the big picture inequities in higher education admissions, you realize that simply pulling for your own advantage and not caring about anybody else’s is just not living up to your own values.

I’m, I’m interested in again, how is this imaginary future college student who reads your book and the kind of attitude that he or she takes when sitting down to take an sat or an act knowing that knowing that there’s a way in which it shouldn’t matter and yet we have to take it seriously. So, so I’m imagining a high school senior or high school seniors parents right in the thick of essay writing. It’s September, I’m thinking about next year and what, what is the piece they make between the knowledge you’re giving them about inequity and the kind of, but I still want my child or I am a child and I still want a college education. And I understand, you know what you said about maybe there’ll be the reformers but before they’re the reformers they have to, you know, get those letters in April.

Yup. Yup. I know it’s, I mean I feel like it’s a real dilemma that I don’t, I don’t yet know the answer to. And every time I talk to talk to parents, students, I, I think about it. I mean I feel like they’re, one of the things that comes through to me in, in the book and in my reporting is that there are these different approaches that low income and high income students are taught when it comes to higher education. And in example, after example, a higher educated higher income students are taught to think of education as a bit of a game. So this sat tutor who I write about, it encourages them not to take the sat seriously and to think like it’s just a game. It’s kind of a scam. You, you know, don’t think that this is really a sign of your, your value or your, or your worth as an individual.

It’s just like your, your ability to do well on this test. It’s just an ability to outsmart these test makers. Right? And then the same thing happens in class in, in, in college itself where low income students are, have this very, you know sort of philosophical idea about how important the actual work is and how important grades are. And I think hiring income students are, are taught to be a little bit cynical about it and to think really big, you know, it doesn’t matter who you know and not what you know. And so I think that that the fact that high income students are taught that sort of cynical approach to school is on the one hand sort of smart and strategic because, you know, a lot of those things are true. That is sort of the way the world works, but it also has the effect of making them cynical which I don’t think is the way we want our teenagers to be.

And so that, that’s why I feel like I keep pushing back toward this idea of encouraging teenagers, high school students to look at the big picture of the system and ask themselves the role that they want to play in it. And to be more yeah, to look more at the system and not just at themselves. And so I don’t, I don’t know what, what decision that leads do in any individual students. You know, I think some of them, it will steer them away from college. Some of them it will make, make them, you know, apply to the same kind of colleges, but with them more a more strict, clear purpose in mind. But I think, I think not doing that, encouraging them just to think of it as a system in which they’re their only goal is to get the best thing for themselves.

He both leads to an unfair system, but it’s also unfair to them. Because it, it pushes them toward a kind of world cynical worldview that I don’t think is what we want for our kids. I don’t think that’s a, that’s, you know, an answer that is completely a gift, a clear picture of what, what each parents should do, where you should apply and how you should apply and how you should study. But I think that, I think it’s true. I think, I think we do have to complicate the system for our kids rather than just simply,

Right. Well, this is this just, this book just gives, like you said, it gives a parent so much pause and reason to wonder about where our child is going to get the kind of confidence that we want them to have. I mean, you want them to have confidence. I don’t mean confidence just because somebody wants to go to Princeton. I just mean enough confidence to pursue what they really want and not let the institution kind of tell them you’re not good enough. One of the things that’s been said by a lot of different analysts of our college system is that it may be we’re sending too many people and as you just said about your chapter seven, there should be somehow an alternative to the four year liberal arts model. Do you want to talk about the school in the book that you it starts with an a and it’s in Chicago, I want to say,

Yeah. A roof, pay a roof, pay college,

What they’re doing that’s completely different.

Yeah. So I, so to answer the question that was sort of embedded in that question, like do I think too many people are going to college? I, I don’t, I don’t, I mean, I think, I think there are a lot of people who we have not properly prepared for colleges and, and for college and a lot of colleges that aren’t properly prepared for the sort of students who are coming who are coming in and you need more education. But I am, I really remain convinced by all the data and, and economics literature that in fact a college degree is more valuable now than it has been at any other time in American economic history. And that there, there is no question that a college degree is on the whole a good investment. That said, there’s a lot we can do to improve the system, but I don’t think that the problem is, you know, too many students getting too much higher education.

That is not the case. But yeah, I think a [inaudible] is an amazing model for one of the ways that we could change higher education is a two year, a pretty new two year college in Chicago that is associated with a four year university Loyola, which is a prestigious Catholic private institution with a mostly well-off high achieving, high scoring student population. And that’s not the kids who are to a repair route. A is mostly educating pretty low income. Chicago public school graduates with relatively low test scores and yet they are not trying to push them all in a vocational direction. They’re giving them this sort of Jesuit based liberal arts education for two years that is designed to prepare them to go on to four year colleges and they take a very different approach than most community colleges do.

They focus a lot on, on low cost and making sure students don’t have to pay too much, but they also have this very what, what the Jesuit priest father through Rose who runs it, calls a, a very intrusive culture. Meaning that the educators, he and the other educators who run the school really take an interest in their students’ lives and not just their academic lives, but everything else. And they do their best to, to help their students in whatever way they need to. So it’s a really thorough going kind of approach

In the sciences. A lot of, I follow a lot of people that are in graduate education and they in order to be encouraging of future PhDs, they will post, I got a C in calculus or I got a 2.8 when I was this age or you know, all trying to support the notion that there’s nobody born to be a PhD and, and it isn’t easy. And and, and also that the self doubt is completely part of the road. Your road will include self-doubt.

Right. I think that’s so youthful. I mean I think, I think, you know, you, you mentioned posting it and which makes me think about social media and I think that that, I think there is a lot more of sort of sensible understanding of how to convey those messages to people. The, the messages of, of, you know, struggle and failure being part of the process. I think working in the other direction in social media, there’s so many students that I talked to who would say like that they are, especially in freshman year that they’re, they’re watching their students who graduated from high school with them who are off at other institutions. They’re watching them on Instagram and Facebook and Snapchat and everything else and feeling like everyone else is so much happier and like, because that’s the way we do our social media. We, we emphasize the good times. And so I feel like so many college freshmen now are having that experience of feel of the, the sort of social media. The grass is greener on the other side feeling and, and if anything, I think that makes it harder.

I think the social isolation is a theme that appears in some, several different stories of people we meet in your book that they feel as if sometimes it’s economic, sometimes it’s cultural that, that their, the in an extreme minority of whatever class they’re in. And I think it’s interesting that, do you ever question whether by trying to have diverse populations of students, we are somehow forcing some of those students to be the only representative of their culture. And so they’re they might have an emotionally better four year college experience somewhere that was less prestigious, but where they felt like they belong.

Yeah, I think about that a lot about that a lot. There’s one student in particular, Matthew Rivera, a student at Trinity college in Hartford, who I wrote about who you know, within this, both very academically prestigious but also very wealthy and white institution. And he was the low income Puerto Rican student from the Bronx. And so he just felt culturally completely out of place. I felt like the students didn’t want them there and it felt a very little sense of belonging. And one of the ways that he described thinking in his freshman year was, should I transfer it to, I think it was the state university of New York and Albany, where some friends of his were. And he was like, I know that it’s not gonna be as good an education, but I’ll be happy. I won’t feel miserable every day. And so I think, but I think obviously the fact that we, we would force or even incline any student to have to make that choice is completely wrong.

And it’s just, it’s just an a factor of admissions. Like if, if those institutions continue to admit just a tiny number of students like Matthew Rivera, then those students are going to continue to struggle emotionally and psychologically, even when they’re succeeding academically as he was. And so, but if he’s part of a group of, you know, 20% or 30% of the freshman class rather than eight or 10% of the freshman class, it’s gonna feel very different for him. And I think, you know, the, the institution itself as Trinity was beginning to do when he, when he got there the institution itself can also just do some very basic things to make students feel more connected to them and more of a sense of belonging. So I think, I think it’s a solvable problem. I don’t think the solution is that the students like Matthew should always go to the state university of New York and Albany. I think it’s great for them to have academic experiences that challenged them and push them and provide them with opportunities. But I think there’s lots of the institutions can do to make them feel more welcomed.

By the time you’ve finished the process, I think you might have in your mind, Oh, I wish I could write a book that was just about chapter six because that was actually, do you have it? Do you have the next, do you have any ideas about what your next really long article by be about there,

There is a section of the book that I do feel like yeah, this is what I’d like to explore more and it’s chapter seven the chapter about students who came out of high school without a particular love of school and wanting to find some other kind of pathway. And the students who are, I wrote about one ends up doing factory work, one ends up doing office work. Women ends up in fast food, but all of them feel this, this pressure to get more credentials in order to succeed. And they try different options to try community colleges. They try a sort of apprenticeship programs and they have different degrees of sort of success and failure. But what that chapter really exposed me to was the fact that we just have a terrible system in place for those students. Like, you know, even for students like yogurt though when I wrote about at Princeton it’s rough enough being a low income student, a even at a highly resourced institution like that. But being a low income student at a community college or sort of anywhere in, in are very sort of slapdash and haphazard system of higher education is so difficult. And it’s those students who, who really we need to help them most are. We just, we like if they, if we aren’t able to get them some kind of credential, they are going to have a life of stuff, low wage service or manufacturing jobs and we’d need to do a lot better by them.

Hmm. So the kind of anti college anti college success or [inaudible]

Yeah, I mean I think it does involve college. I mean, I think, I think a big part of the solution is community colleges. And right now we just don’t, you know, we have cut our funding for community colleges by such a incredible degree that they just don’t function as well as they need to. In fact, you know, but those are the students who need more help rather than less help and we just keep giving them less and less help. So I don’t think the, I don’t think there is a great path that doesn’t involve college for those students. It, they certainly don’t all need four year degrees, but we need to provide a lot better options for them and fund those options a lot better.

Paul tough will be coming to our forum stage on Friday, October 4th, 2019 to talk about his new book, the years that matter most. If you’d like to ask Paul a few questions or get a signed copy of his book, make your way to the forum stage a town hall, Paul’s event will start at 7:30 PM and we still have seats available so you can purchase tickets at the door or on our website at town hall, seattle.org

[Inaudible].

Thank you for listening to in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle baseband, EBU and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. If you can’t make it to a town hall event, you can always listen to our series, podcasts, arts and culture, civics and science, or if you’re more of a visual learner. We have a whole library of live streams and videos on our YouTube channel. Just search town hall Seattle and subscribe. Next week, our chief correspondent Steve, we’ll be in conversation with Melanie Mitchell about the successes, hopes and fears of artificial intelligence. Till then, thanks for joining us right here in the moment.

[Inaudible].