In this week’s interview, Chief Correspondent Steve Scher talks with Conor Dougherty about the fight for housing in America. Dougherty outlines why developers aren’t building homes for millennials the way they did for baby boomers, and explains the factors that led to this decline. He discusses the rise of Nimbys (“not in my backyard”) and the growing movement against gentrification. Dougherty encourages us to ask ourselves which outcomes we want when it comes to housing, and encourages us to petition for big-picture solutions like rehabilitating affordable housing, increased density, and lower cost housing production.

Episode Transcript

This transcription was performed automatically by a computer. Please excuse typos and inaccurate information. If you’re interested in helping us transcribe events and podcasts, email communications@townhallseattle.org.

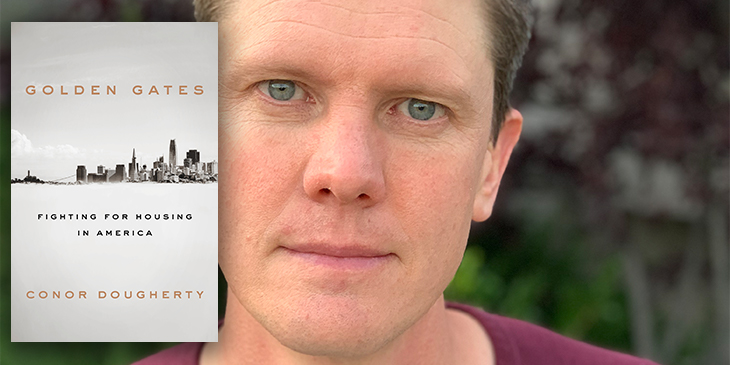

Welcome to in the moment a town hall Seattle podcast where we talk with folks coming to our stages and give you a glimpse into their topic, personality and interests. I’m your host, Janine Palmer. We need more housing in America. Every presidential candidate is talking about the need for more affordable housing. In the meantime, people are being priced out of the opportunity for a stable home in cities across the country. How will more affordable housing get built? Will existing homes be torn down or preserved? Will the federal government build housing for the millions of millennials who are locked out of the market? The cost of housing is a national story. Groups are fighting towards the same goal, but with different strategies. NIMBYs not in my backyard. [inaudible] yes, in my backyard. Anti gentrification groups, developers, low income housing and nonprofits, tenants rights groups all speak to the need for a diverse response. Are we getting the diversity of policies we need to create diversity of houses? Connor Doherty is an economics reporter for the New York times. He has covered housing issues for more than a decade. His new book, golden Gates, fighting for housing and America delves into the affordable housing crisis in one city, San Francisco. And what it means for the rest of the country. Dowdy is coming to town hall. Tuesday, February 25th at 7:30 PM he spoke to chief correspondent, Steve share about the crisis and the response from many of the democratic presidential candidates

half the time the plan wants to talk about housing as a, as a route for asset building, you know, for making families better off but then half the time it wants to sort of penalize private developers and sort of act as if profit making is bad. And um, I’m not saying it’s hypocritical or inconsistent, I think would it, would it genuinely does it sort of capture these dual roles of housing? People like it when a home is stable and it increases in value and people can use it semis their retirement plan but they don’t like it when it seems like some developer is raising rent exorbitantly cause they’re trying to make a return. But I think what we’re starting to acknowledge and what those plans are starting to acknowledge is that these are the same thing. If you’re going to enrich a bunch of people who have, you know, planted themselves on land in single family homes many years ago and purely by accident of timing, they have built substantially more assets than other people.

Uh, the, the same forces that are creating not at the same forces that are, uh, forcing developers to or that are inspiring, I should say, developers to, you know, really, you know, increase to build luxury and to go rent. If there was a, a really great business in building middle-class housing, which there used to be, people would be doing it. And what I think is significant about it, just to reiterate, I think what is significant about all of these plants is that it does every single one of them in some fashion or form says we need a higher intensity of land use.

When you looked at the different, um, histories that evolved, did you find any moment that said, Oh, this is where it shifted from being a good deal to build middle-class housing, lower middle class people could afford to, where it just was not penciling out for developers? And would, would you point to any particular regulation, zoning or shift in values that brought that about?

Yeah, I would say. Okay. So let’s just start by saying spacious. Affordable housing was in the post war period that he seems killer symbol of American affluence. When we thought about what does it mean to live in a rich society, not a society with a lot of rich people, but a society with a whole society seems richer than in other countries. What does it mean to have a solid middle class? Housing was always the symbol of that. And for decades and decades and decades, observers from Europe and other countries would always note that. So then look at where we are today, where housing is the singular symbol of inequality. It is absolutely, uh, our, our most vivid example of how the economy has gone wrong. And when people from other countries, Europe and elsewhere visit, they see destitution on the streets and don’t understand how this could possibly be happening.

So clearly over a very long period, something went very, very wrong. I guess what I would say is that it seems to me that somewhere around the 70s, the economy broke in a multitude of ways. Uh, this is the same period in which you’re going to see, cause there’s a lot tied up in this, right? This is the same period in which you’re going to start seeing union membership plunge. It’s the same period in which financialization of the economy starts to take off. It’s the same period in which, uh, wages start to sag stagnate. But somewhere around the late 1970s, uh, nimbyism really took hold, uh, at the same time, inflation caused people to see their homes much more as a, as an asset. And it’s not like anybody ever thought they’d lose money on their home, but I do not. But it is, it was not true pre the late seventies that people thought about it as an investment that they would profit pretty substantially from.

So I think that, uh, the, the, the land use, um, restrictions, uh, were a huge, huge, huge piece of this. Um, but you know, a lot of other things were happening in the economy. Um, and, and you know, all of them kind of tied up together. One thing I would also note is that, um, I think that’s, uh, I think there’s these generational ebbs and flows to the kind of play into this. Like there’s this just like surge of millennials and we’ve never built for them the way we built for the baby boomers. I mean, you read stories about, you know, I think that paid a piece of home-building grew by like 10 times in like five or eight years after 1945. So we never, uh, I mean we never did that for this generation and I think that it’s kind of left us in this hole for most of our history. Uh, we have solved housing problems by solving transportation problems. We had, you know, horse drawn wagons and then coaches and buses and trains and then freeways and we just sort of linearly than geometric. We just added more and more and more land for development. That system has basically broken. You cannot just like drive somewhere 300 miles an hour. Now the way, you know from say 1900 to 1950 how much land was accessible in a short trip was, you know, radically altered.

Your point about I’m never building for the millennials is really profound because that’s, I mean it was a national effort after world war II to give folks housing and access to housing and that has not happened. Who kind of caught people by surprise that there were so many millennials though it shouldn’t have. Of course there’s a lot of demographers, you know, you looked at this writing as an economics reporter and one of the things I was, I was curious about was how you do think about the anti-gentrification movement. So for example, in Seattle, the central district was the, was the central cultural node for African Americans. And it was many, many single family homes, apartments too. But it was many, many single family homes. And of course they’ve, they’ve been pushed out by gentrification. They’ve sold by gentrification and moved to other places, made some money on their houses, or they were renters, they didn’t want to leave. That’s repeated itself in many neighborhoods. Right. Including South of mission in San Francisco. What solutions work for those people who say, look, I want to stay in my neighborhood around my culture?

It’s an absolutely crucial question. And one of the things I try to Telegraph with the book is just having both sides of this equation work together. Uh, you know, the reason redevelopment went so poorly in the, you know, postwar period, the reason it was, you know, became a vehicle to clear black neighborhoods and commit some of the like worst sins we’ve ever committed. Was it, nobody from those neighborhoods had any kind of power or influence whatsoever? Uh, so I guess I think w I don’t, I don’t, I don’t really want to start prescribing solutions. I just want to say those neighborhoods need to be present, prescribing their own solutions. Uh, I think so, but you know, I’ll tell you that some of the ones I’ve heard are a lot social housing, um, a lot more. Um, you know, using community land trusts, uh, these are all very good ideas that can be scaled and it can and do not have to be in conflict with new building, uh, as they currently are.

One of the great anecdotes I have in the book, or at least one of my favorites was this nun who, uh, lives who, who, who works across the street from this building. Uh, it’s a 50 unit apartment building and this investor came in, bought it, evicted everyone, kind of, you know, gave it fast wifi and a coat of paint, uh, raise the rent substantially. And then nun was so outraged by this. She got together with a bunch of investors. Um, she really worked hard to, to hustle and bought it back, uh, and has now turned it into permanently affordable housing. I think that you can do a lot of that type of stuff. Uh, there’s no reason why affordable housing funds that are currently going to build affordable housing. Some of it could go to preserving. I mean, they do that in San Francisco, in Oakland and other places. Rent control is another. Uh, I think rent control should be done gently, or at least the evidence suggests it should be. But, um, but I mean it’s certainly part of the policy solution.

You have looked at rent control. What’s good about rent control? Where has it worked well and what are still the, the problems that rent control might cause?

Let’s just get away from rent control for one minute and ask this question and start with this. America has in a multitude of ways decided that it wants people to have stable homes. Um, the mortgage interest deduction, which, um, you know, the entire apparatus of Fannie and Freddie that essentially exist to create the 30 year fixed mortgage. We have, uh, let’s see about the mortgage intersection, but the 30 year fixed mortgage, you cannot go America’s like the only country that has a 30 year fixed mortgage. And we’d go through all this effort because we basically have decided we don’t want P we want to insulate people from rapid increases in their cost of living. So rent control philosophically is just saying people should, people who are venting, we play a very vital role in their local economies. Should a have the same kind of protection that homeowners get at substantial federal costs?

It is not, it is not cheap to create a whole apparatus to create 30 year fixed mortgages. So let’s just start with that as the framework. The problem sometimes is that, um, rent control can, uh, it can a, uh, remove the profit motive, which nobody wants to hear. But that’s, that can be a problem. Yeah. Private in a market where we still, most of our housing is still built by private builders. That’s a problem. And then B, it can, um, encourage landlords to exit the rental business. If you’re going to get way more money by selling it off as ownership housing, you will do that. If you look at the mission in San Francisco, which has been an intense battlefield, although most of the most intense gentrification happened 20 years ago, um, that neighborhood has a ton of old, I grew up right next to the mission and noway Valley.

So I have a pretty clear sense of how it’s changed. Uh, it’s become a lot of, you know, these condos that used to just be like affordable flats. So everything that economists predict, rent control will do is happening there. A lot of people will say, Oh, well if you just change these laws that make it impossible to convert condos and all that. I, I guess I, I, you know, those are all things you should do probably in an emergency. But I think that one of the things rent control does is it kind of, it, it insulates people. It’s like, I dunno how to put this without sounding a heartless. It’s like you want to insulate people, but you don’t want to insulate them too much. And, and I, I guess what I’m saying is you want to insulate people, but you don’t want to insulate like society.

If our rents are increasing by insane amounts, we should take that as a cue to start building. And sometimes what rent control does is it, it just, it removes political support for this thing we need to be doing. Uh, so what, what does rent control do? That’s good. It gives people stable homes. It gives them a predictable budget that they can start saving for their kids’ colleges. They can, you know, I mean, people can just, just imagine how much you can plan when you know what your living costs are and imagine how much a life is thrown into chaos, uh, if, if, uh, if you don’t, so that’s an important societal goal. Um, the question is, uh, is rent control always the best way to achieve it? Um, some economists have talked about, uh, you know, doing, um, a giant renter’s tax credit. So like you’d still be insulated from large, uh, rent increases, but it wouldn’t change the price.

Um, it would change the price for you, but it wouldn’t change the price. Um, and therefore developers would keep building, by the way, I should also say, and um, rent control essentially does work as designed. Um, you know, there is numerous studies show that the people we want to benefit from rent control do benefit who are in shore. Now, of course the thing studies also showed that people who are quite wealthy also benefit from rent control. Some people are okay with that, other people think it’s a giveaway. I’ll flip them, hash that out. But it clearly has some bad effects as well. I mean, I guess this is probably true of most policies though, right? You know? But anyway, as you can tell, I’m sort of conflicted about this because the goal of rent control is pretty much, it’s an important goal and it’s one that we’ve codified into various other aspects of our housing market, but we never talk about it.

You know, again, notably that the 30 year fixed mortgage, I would say one of the things I’m really happy about right now is that it seems like people are like experimenting with rent control. I mean the distortions of if you talk to economists, they, they, there are gradations of rent control and a lot of them are not nearly as disruptive as others are. So I think the fact that we’re running this policy experiment and passing lots of different kinds of rent control in different places, some with varying levels of intensity. I think that’s like ultimately a good thing. I also think though philosophically people should also ask themselves what works like, I mean this is the thing I feel, I mean is this nimbyism thing working out for us? It really doesn’t seem to be. So I think that when people, you know, if, if, if we pass super hard rent control and you know, w and nothing happens, well we shouldn’t be so ideological about it.

We should just be like, wow, that worked great. Turn out the economists were all wrong, which they frequently are all the flip side. What if we pass something and you know, all the worst things happen and you know, we have to ask ourselves, well is this, I mean this is one of the things that frustrates me about policy generally is it doesn’t seem like there’s a lot of, I feel like rather than being dogmatic about which policy we want, we should sort of ask ourselves. I mean I’m being a little bit Pollyannish here. I realize, but which outcomes we’ve won and what gets us there, I don’t think we should be so rigid about which policy. I think that all of these policies have to be part of the solution. If this, if you and I were talking 40 years ago, I feel like we would have a totally different set of solutions. I think if this was 40 years ago, I would probably tell you we should just be building more and that the private market probably could take care of a lot of this, but we’re not there now. We have dug ourselves into a 40 year hole and we’re not going to just get out of it by unleashing the private market or by just passing rent control on the existing housing stock.

Well, can we do something by, uh, you know, returning to a more vigorous and robust federal housing support and federal housing construction program?

Absolutely has to be proud of this because I mean, particularly in California, I mean, we’re looking at problems that have a lot. Omar acknowledged this with her housing plan. We’re looking at problems that have trillion in the dollar figures. We’re not looking at a problem that has billions or even hundreds of billions, this a multi trillion dollar problem. And I also think one thing we don’t think about enough is how costly inaction is. I mean, homelessness consumes all sorts of local resources that are never Kaleed. Um, police action, emergency room visits, you know, all this costs from homelessness. But we, we, we, you know, obviously beyond the moral cost to that we just don’t have to incur if we built housing, um, you know, and, and, and, and supportive affordable housing. I think also, uh, you know, one of the, uh, you know, in the book I followed a family as they were displaced, the daughter and the family, you know, lost like a month of school. God knows what kind of, uh, what happened to her homework, uh, during, um, the chaos of the three months not knowing where she was going to live. I just think that the cost of that is quite hot. Uh, so as costly as it will be to solve this problem. I truly think, and multiple studies have shown versions of this, that the cost of inaction is substantially higher. We just don’t see it as obviously,

well Omar, Omar talks about, uh, 80 billion for public housing agencies, 200 billion over 10 years for Obama’s housing trust fund. Just as a way to get people into housing. You know, as you said, $1 trillion, 12 million new homes over 10 years. But the problem we seem to face is that can people build affordable homes and buy affordable, I mean like affordable for somebody who’s making 40,000 a year in this country. Even that’s high. I mean, can, is there the ability to do that without either, you know, what the argument is not just changing zoning laws but changing rules and regulations so that may make for less safe and less efficient and less, um, substantial housing stock.

Well, I mean if you do it like Alon Omar claimed to do it, which is, um, you know, subsidizing it. Yes, of course you can build it that way. You know what I mean? When housing was a portable, effective median income was, was much higher. Right? I mean, if the question is why can’t people afford homes? Part of the reason is the homes are two insects. If this a fair, large part of the reason, but it’s also that they don’t make enough money. Um, so, okay. So one of the things I started to kind of foreshadow a little bit in the book is there’s this developer who’d been building affordable housing his whole career. He, I actually kinda liked him as a character who beat into the book when he’s 10 years old, moving to California, just, you know, full of optimism and, um, maybe became an affordable housing developer in the 70s. Now he’s 65 and he’s trying to build supportive homeless housing. Uh, and, and he’s using a modular housing factory to do it.

What was his name? What was his name?

His name is Rick holiday. He is the founder of bridge housing. The other guy was Don Turner, who, who was a, um, kind of a lion of the housing world. He was, he was part of the Bronx co-ops, which has been a very successful model for rehabilitating affordable housing. So what they are, what would, I’m sorry Don, turn this in dead for many years. But what Rick is now doing is, uh, is something a lot of people doing, which is trying to build housing indoors and do it on a production line so that the cost becomes much lower. I am not here to say that this is the best idea in the world or that, um, you know, that this is the savior or any of that others. But I am here to say that tinkering with new technologies and asking the question, how do we actually build a house for far less money is going to be an important piece of this.

Um, I think that, you know, when you unleash whether or not anyone likes it, when you unleash the private market in America in, in ways that are generally productive, it tends to evolve at a scale that the government just simply can’t compete with. I think new technologies are going to be a piece of this. You know, in California right now, uh, just despite how high it is, despite the fact that, um, you know, people can sell 3 million condos and $4,000 a month, one bedroom, uh, housing production is fallen. And one of the reasons it’s falling is that developers simply can’t build, the construction costs are rising so fast that they cannot build PR profitably, even with 3000 to $4,000 a month. I don’t want to also be like, Oh, technology is going to rescue us because this is a public problem. This is a policy problem. It’s going to take tons of money from the government. It’s going to take, you know, tons of political will, but, but technology should be a piece of that.

What does San Francisco, let’s say inner and outer Richmond, you know, that area where it’s just a house after house, after house while sharing walls in San Francisco. What would that look like if the, if it was unleashed, if the zoning changed and if the demand for housing was met by some kind of ability to provide supply, I mean, would those neighborhoods be substantially changed?

Let’s remember that. That’s what they did look like. Regeneration. Uh, everyone who’s listening to this interview should go Google painted ladies San Francisco and then hit a Google image. Uh, have you, have you been to the painted ladies? Have you ever seen the painted ladies in person?

Yes. Yes.

Okay. So what did you remember about them? Tell me what you remember.

I remember they’re tall. I remember they have big porches.

So the one thing you probably don’t remember, and the thing that is always cropped out of the picture in the beginning of the show full house, which is what made so extra special, iconic, uh, is that there is like a seven story apartment building butting up the last of one of them. It is right there is, there was a step, I don’t know if it’s seven stories, but there was a at least five story apartment building right on that block right next to them. Right? That is what that neighborhood looked like. And neighborhood was built. Like if you go out to the, to the Richmond, to the sunset, there were apartment buildings, three, four or five stories. Um, all over those neighborhoods. Uh, they, they, they existed in harmony with single family homes for decades and decades and decades. And I think that, um, one of the things I talk about in the book is, you know, in America a lot of this has to do almost like with listen with like our mindsets, you know, like what we think should look good.

You know what I mean? If you go to other countries, you know, they might dress and you know, their fashion might be different, right? I mean, to some extent, uh, our, our, we have this notion of what we think a neighborhood should look like. And we’ve got this mindset that, Oh my God, why could you never put a apartment building next to a single family house? Well, why can’t you? There’s no rule that says you can’t do that. There’s no, um, it works plenty fine in places, in other places. In fact, the hilarious thing is in other places, it does not affect the property values though it will here. And the reason it doesn’t affect the property values in other places if they don’t care. So part of the problem is we just like care. We’ve got it in our heads that this is some, you know, you know, wild nature that we can’t violate, but it’s nothing of the sort.

And I guess what I’m what, so a lot of this is just basically cultural. Uh, and so we created a new kind of culture where we decided that it was just like, didn’t look right unless they had all of one type of building. Uh, and that’s, that was essentially a cultural decision. And we now, I mean that’s kinda what I meant when we were talking earlier in the, um, in the, uh, in the interview about how is this going to hold, really can be, you know, keep this ethic for their whole life. And I think if they start to live in a world where they think it, it looks cool, it looks neat, it looks, you know, interesting. When an apartment is next to a single family home, I mean, that alone can be a pretty significant shift. You know, I mean, I, I just, I think that kind of it, so this is all just a, a, a passionate way of saying that there’s, if you go out to neighborhoods that are, um, you know, inner urban neighborhoods with a lot of single family homes, most of them will have in Seattle, in San Francisco, in a million other places.

We’ll have apartment buildings sprinkled in. No, I’m not talking like 30 story towers. Um, but I’m talking, you know, three, four stories. Some of them are even only just two, two, but they’re, but they’re kind of blocky and inefficiently laid out.

The problem is in Seattle, those are the ones that are getting knocked down and replaced by either large apartment buildings or replaced by large one or two or three townhomes. So we’re losing, we’re losing housing stock that was affordable, uh, in those, because those very small apartment units are getting torn down and you know, but it’s like a monoculture, right? We built a monoculture of these. San Francisco’s like that, Seattle’s like that and spreads for a long ways and now we’re starting to see the need for diversity. I was, I was struck by that you have these three tribes that, you know, these two groups that you talk about and there’s many more, but the anti gentrification folks, the NIMBYs yes. In my backyard. Let’s build up and let’s, let’s get dense. And the NIMBYs who say, no, not in my backyard. Did you find any place it were, those individually, you write about these individuals and the races they run for politics, for political office. Did you find any place where they were um, starting to come together to work together?

Yeah, Oregon, right next door to you. Um, uh, in Oregon they had a very success, they, the um, the, um, in Oregon last year they passed, uh, at statewide rent control. It’s a very wide rent cap. Some people like to call it, but you know, it, it, it’s uh, it’s a pretty, or cap, I think it was like 7% or something like that. Um, then, um, and, and they also essentially banned single family zoning at the same time. So that is an example of a mixed solution. They probably could have, you know, I’m sure people could quibble with the details, but I mean this spirit of that have to, uh, have a preservation solution and a production solution coming together and perhaps more importantly the constituencies kind of getting to know each other and realizing that you don’t have to be each other’s enemy. I will say, I hate saying this, but it is true.

Uh, San Francisco has like a particularly toxic political environment and a lot of times that toxicity is its own kind of its own impediment to things. You know, people just playful contact here and they decide their enemies are their enemies and that’s just how they go about it. Um, I think, you know, it’s kind of funny in, you know, in the whole UMB world, they can be in San Francisco, I’ve gotten kind of like a bad reputation, but having grown up in San Francisco, I’m just like, no, that’s just how San Francisco is. Uh, but in, in other places where the political culture is not so, you know, kill or be killed, um, the, you’ve seen all sorts of things in San Diego. I mean, to a lesser extent, I don’t know how it is in Seattle, but I know in Portland and in Oregon there’s been a lot of um, you know, a lot of forward momentum.

And, and also by the way, I’m not in any way saying that the different sides of this fight has to become like best friends and everyone hold hands and say kumbaya. You know, maybe it’s completely fine if, you know, uh, one year we passed a housing production bill and the other side is mad and then the next year we passed the big rent control bill. Um, but by the way, I will say I’ve never seen the housing production people, at least the younger ones be anti rent control. I’ve seen them, you know. Anyways, so I guess what I’m saying is, is that there’s all sorts of great examples. Um, I don’t know that Minneapolis is the best example cause they haven’t done much on tenants just yet, but they certainly essentially ended single family zoning and the in the city.

That’s right. We do have that whole question of tenants rights and we’re tenants and this large rental pool. And ever expanding rental pool, what impact or political impact they might have as they get organized?

Yeah, and I mean, look, I don’t want to be, I don’t want to be like silly about this. There are lovely, wonderful places like Seattle and San Francisco. They’re going to be expensive. They pretty much have always been expensive. The question is how expensive do they need to be and are they so expensive that working people cannot even get a hold there. You know, even when San Francisco was, I mean, San Francisco has been pretty expensive since the 70s. A lot of people locally will say, Oh, that’s not really true because I got an apartment for 100 bucks. But, but that’s relative to the rest of the nation. The Bay areas, housing costs went from being roughly the same to about 50% more between 1960 and 1970 and a lot more people move there for mentioned 50 to 1960. So the main thing that changed was they stopped building house. But, um, and, but, but even when, when things were that bad, there were still neighborhoods people could live in.

There were people who bought home, have lives, you know, I used to think of Potrero Hill, it’s like the affordable place. Uh, and now, you know, you see you’ve mentioned or not mentioned, but you know, like the kind of glass modernist homes with the songs to respond. Yeah. So, um, so I guess, uh, I think that it’s all kind of quietly happening. Hey, you and I are talking about this, the presidential candidates are talking about this. Um, even in the Sims, the school board of supervisors, people who have kind of essentially been NIMBYs in the past or are talking about their housing production solution. And it’s much different than the, and be one who cares. It’s it, everything is congealing a particular direction right now. It was not even close to that direction, even just like two or three years ago. So I think we should take a moment to also acknowledge like the fact that we’re all talking about this and the fact that there have been some pretty big things, Oregon state wide rankings, you know, in just a few years, um, is, is, is starting to look like progress.

Uh, you know, given that it took us 40 years to, um, dig ourselves into this problem, that’s a pretty good start for two years of acknowledging we need to dig out. I will leave you with this. If there’s one thing that really became clear to me as I wrote this book, it’s that the policy, what we think a particular policy is going to do and what it ends up doing is like, it’s very hard to see that, uh, you know, it’s very hard to predict that. I mean there’s so many times in the 80s, California was passing housing goals cause they had a housing crisis even back then. And people, you know, LA times is writing editorials, Oh this is the end of it. And we’ve, you know, the state of California is going to stop the NIMBY. I mean, people were writing that kind of stuff in like 1982. Clearly that never happened. So I kinda, like I said before, I mean, I think that I, I, my, my Pollyannish wishes that we could have policies that, that were designed around an outcome and would change if that outcome changed. You know what I mean? Like meaning if we passed a bunch of policies and they clearly did not work, we would have the political capital and will to just get rid of them or alter them, uh, pretty, you know, pretty quickly.

Um, I digress a little bit. You sort of see this Obamacare where it’s even Democrats will tell you, Oh, it needs some editing. Um, but, but you know, there’s no, now it’s entrenched and people either hate it or they, you know, it’s just like this, you see this all over the place where once something gets kind of locked in, it’s hard for people to tinker with it. So anyway.

Yeah. Well, it’ll be interesting to see what we’re talking about when you write the write the sequel, the golden Gates fighting for housing in America. I mean, fighting for housing the America in and of itself tells us that it’s a long way from being concluded, doesn’t it?

Yeah. And I think, um, I truly believe this book will have captured unimportant inflection points. So even though the story isn’t over, uh, I think this book captures definitely a beginning. The fact that these presidential candidates are all talking about this, the fact that there’s a huge resurgence tenants’ rights movement that has been like basically dormant since the 70s. The fact that we have this, you know, [inaudible] thing that has all these 25 year olds going into like planning meetings, I mean, whoever thought that would happen, you know, they all, do you want to go to the planning meeting Wednesday what, 25 year old. Yep. He says that. So I think that it’s pretty clear that something is brewing and I think this book takes you deep inside how that happened, who these characters are and you know, ultimately we know where their conflicts are, but, but you know, little with sub where they’re finding common cause and you know, like I said as a gen X or I’m sort of relegated to, uh, observing the world. Maybe that’s why I became a reporter because I’m sandwiched between these gigantic generations. Um, that just, you know, they sneeze and everyone else has to deal with it. Um, whereas mine, it’s like I just, you know, we just had to fit in. So I, you know, sometimes it feels like a good place to be in the middle of these two.

All right. I appreciate you talking to me. I appreciate it very much. Thank you.

Yes. I hope you [inaudible] thank you so much for having me and um, I felt like we had a lot of fun. So maybe all, maybe I’ll find our way through this thing cause it’s kind of on all of us. Thank you so much.

Thanks. Bye. New York times economics reporter Connor Dougherty comes to our forum stage on February 25th at 7:30 PM to talk about his book, golden Gates fighting for housing in America. Thank you for listening to episode 55 of in the moment. Our theme music comes from the Seattle based band, EBU and Seattle’s own bar Souk records. You can listen to the full town hall produced programs and speakers on our arts and culture, civics and science series, podcasts, or if you prefer to watch instead of listen, there’s a whole library of content on our town hall, Seattle YouTube channel to support town hall. Read our blog or see our calendar of events. Check out our website at town hall, seattle.org next week. Steve, share. We’ll talk with Dr. David Eagleman about if we can create new senses for humans. Till then, thanks for joining us right here in the moment.